Universality of Neural Networks on Sets vs. Graphs

Universal function approximation is one of the central tenets in theoretical deep learning research. It is the question of whether a specific neural network architecture is, in theory, able to approximate any function of interest. The ICLR paper “How Powerful are Graph Neural Networks?” shows that mathematically analysing the constraints of an architecture as a universal function approximator and alleviating these constraints can lead to more principled architecture choices, performance improvements, and long-term impact on the field. Specifically in the fields of learning on sets and learning on graphs, universal function approximation is a well-studied property. The two fields are closely linked because the need for permutation invariance in both cases leads to similar building blocks. However, we argue that these two fields have sometimes evolved in parallel, not fully exploiting their synergies. This post aims at bringing these two fields closer together, particularly from the perspective of universal function approximation.

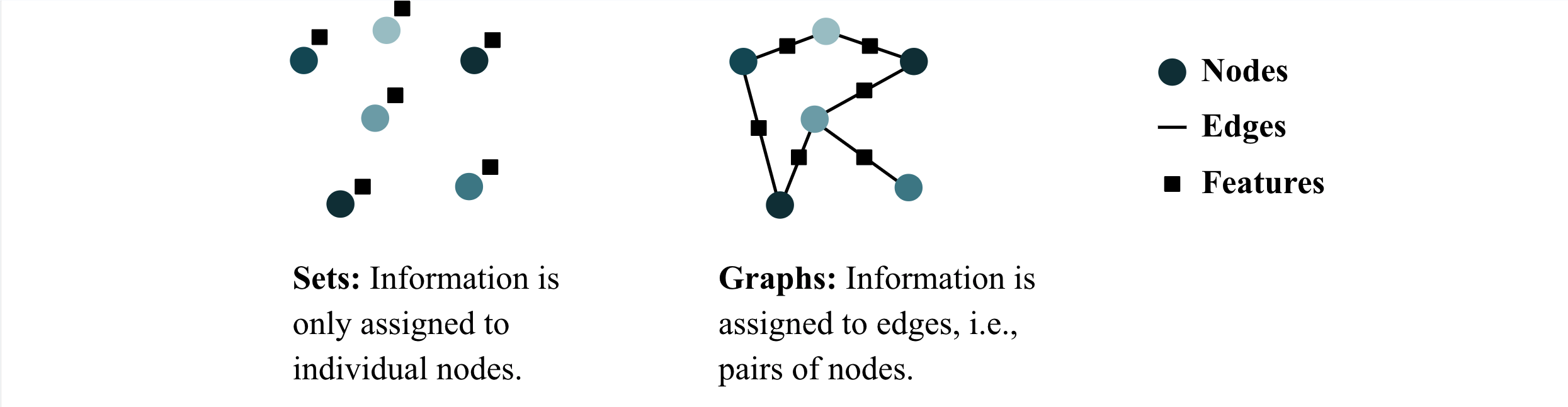

Sets and Graphs

Before we dive into

Examples of machine learning tasks on this type of data include 3D point cloud classification (a function mapping a set of coordinates to an object class) and molecular property prediction (a function mapping a molecular graph to, e.g., a free energy value).

So, what are invariance and equivariance? Both concepts describe how the output of a function (or task) changes under a transformation of the input. Transformation can mean different things, but we restrict ourselves to permutations here for simplicity. A function \(f\) is permutation invariant if the output does not change as the inputs are permuted. The left-hand side of the following figure below visualises that concept:

The right-hand side depicts permutation equivariance: changing the order of the input implies a change in the order of the output (but the values themselves remain unchanged).

Tasks (or functions) defined on sets and graphs are typically permutation invariant or equivariant. This symmetry is often incorporated into the neural network architecture, as we will see in examples below. It is exactly the incorporation of the symmetry that makes the question of universalilty so interesting: is the network (theoretically) able to model all permutation invariant (or equivariant) functions on this data?

Why do we care about universal function approximation?

First of all, why do we need to be able to approximate all functions? After all, having one function that performs well on the train set and generalises to the test set is all we need in most cases. Well, the issue is that we have no idea what such a function looks like, otherwise we would implement it directly and wouldn’t need to train a neural network. Hence, the network not being a universal function approximator may hurt its performance.

Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) by Xu et al.

However, this is not always the case. Sometimes, architecture changes motivated by universal function approximation arguments lead to worse results. Even in such unfortunate cases, however, we argue that thinking about universality is no waste of time. Firstly, it brings structure into the literature and into the wide range of models available. We need to group approaches together to see the similarities and differences. Universality research can and has served as a helpful tool for that.

Moreover, proving that a certain architecture is or is not universal is an inherently interesting task and teaches us mathematical thinking and argumentation. In a deep learning world, where there is a general sense of randomness and magic in building high-performing neural networks and where it’s hard to interpret what’s going on, one might argue that an additional mathematical analysis is probably good for the balance, even if it turns out to not always directly result in better performance.

Learning on Sets & Universality

To prove universal function approximation

The first part says: any concrete implementation of a ‘universal’ network architecture might not be able to learn the function of interest, but, if you make it bigger, eventually it will—and that is guaranteed

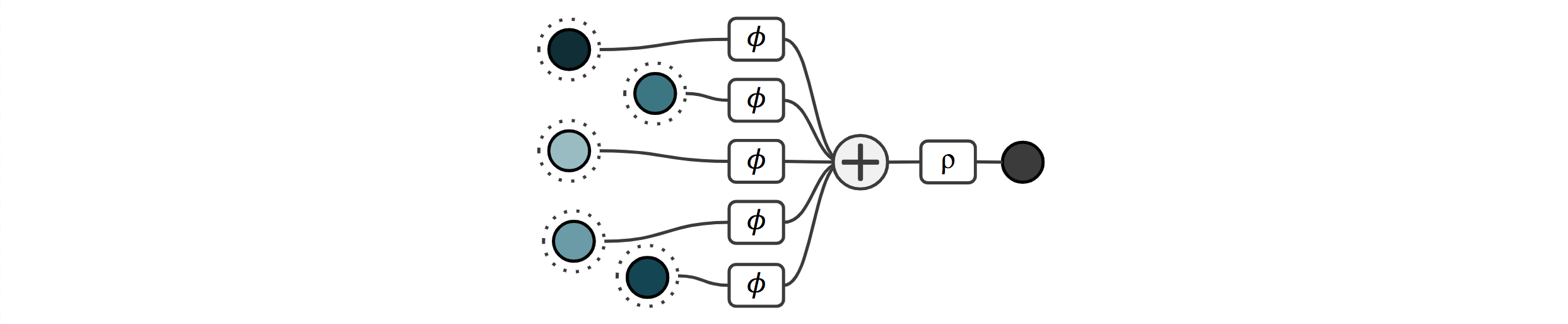

One of the seminal papers discussing both permutation invariant neural networks and universal function approximation was Deep Sets by Zaheer et al. in 2017

Because the sum operation is permutation invariant, the final output is invariant with respect to the ordering of the inputs. In other words, the sum quite obviously restricts the space of learnable functions to permutation invariant ones. The question is, can a neural network with this architecture, in principle, learn all (continuous) permutation invariant functions? Perhaps surprisingly, the authors show that all functions can indeed be represented with this architecture. The idea is a form of binary bit-encoding in the output of \(\phi\), which we will call the latent space from here on. Concretely, they argue that there is a bijective mapping from rational to natural numbers. Assuming that each input is a rational number, they first map each rational number \(x\) to a natural number \(c(x)\), and then each natural number to \(\phi(x) = 4^{-c(x)}\). It is now easy to see that \(\sum_i \phi(x_i) \neq \sum_i \phi(y_i)\) unless the finite sets \(\\{ x_0, x_1, ... \\}\) and \(\\{y_0, y_1, ...\\}\) are the same. Now that we uniquely encoded each input, a universal decoder can map this to any output we want. This concludes the proof that the Deep Sets architecture is, in theory, a universal function approximator, despite its simplicity.

However, there is an issue with this proof: it builds on the assumption that the MLP components themselves are universal function approximators, in the limit of infinite width. However, the universal function approximation theorem says that this is the case only for continuous functions, where continuity is defined on the real numbers. That continuity is important is sort of intuitive: continuity means that a small change in the input implies a small change in the output. And because the building blocks of neural networks (specifically linear combinations and non-linearities) are continuous, it makes sense that the overall function we want the network to learn should be continuous.

But why continuity on the real numbers? Because continuity on the rational numbers is not a very useful property as shown in Wagstaff et al. 2019

What about more complicated architectures? Murphy et al.

Approximation vs. Representation

For simplicity, we have so far deliberately glanced over the distinction between function approximation and representation, but we will rectify this now. The Deep Sets architecture from the previous section can be written as:

\[\rho (\sum \phi_i(x_i))\]If we forget about \(\rho\) and \(\phi\) being implemented as neural networks for a second and just think of them as general functions, it turns out that any continuous permutation invariant function can be represented in the above way. The word represented implies that it’s exact, without an approximation error, not even an arbitrarily small one. As such, Zaheer et al. 2017

What about graph representation learning?

So, this was universality in the context of machine learning on sets, but what about graphs? Interestingly, the graph representation learning community experienced a near-identical journey, evolving entirely in parallel! Perhaps this observation comes as little surprise: to meaningfully propagate information in a graph neural network (GNN), a local, permutation invariant operation is commonplace.

Specifically, a GNN typically operates by computing representations (“messages”) sent from each node to its neighbours, using a message function

where \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\) are the features of node $i$. This is followed by an aggregation function which, for every node, combines all of its incoming messages in a way that is invariant to permutations:

\[\mathbf{h}_{i} = \phi\left(\mathbf{x}_{i}, \bigoplus_{j\in\mathcal{N}_{i}} \mathbf{m}_{ji}\right)\]where \(\mathcal{N}_i\) is the set of all nodes neighbouring $i$, and \(\phi : \mathbb{R}^k\times\mathbb{R}^l\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^m\) is an update function, updating the representation of each node \(i\) from \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\) to \(\mathbf{h}_{i}\).

Opinions are still divided on whether every permutation equivariant GNN can be expressed with such pairwise messaging, with a recent position paper by Veličković

Therefore, to build a GNN, it suffices to build a permutation-invariant, local layer which combines data coming from each node’s neighbours. This feels nearly identical to our previous discussion; what’s changed, really? Well, we need to take care of one seemingly minor detail: it is possible for two or more neighbours to send exactly the same message. The theoretical framework of Deep Sets and/or Wagstaff et al. wouldn’t entirely suffice in this case, as they assumed a set input, whereas now we have a multiset (a set where some elements might be repeated)..

Learning on Graphs and Universality

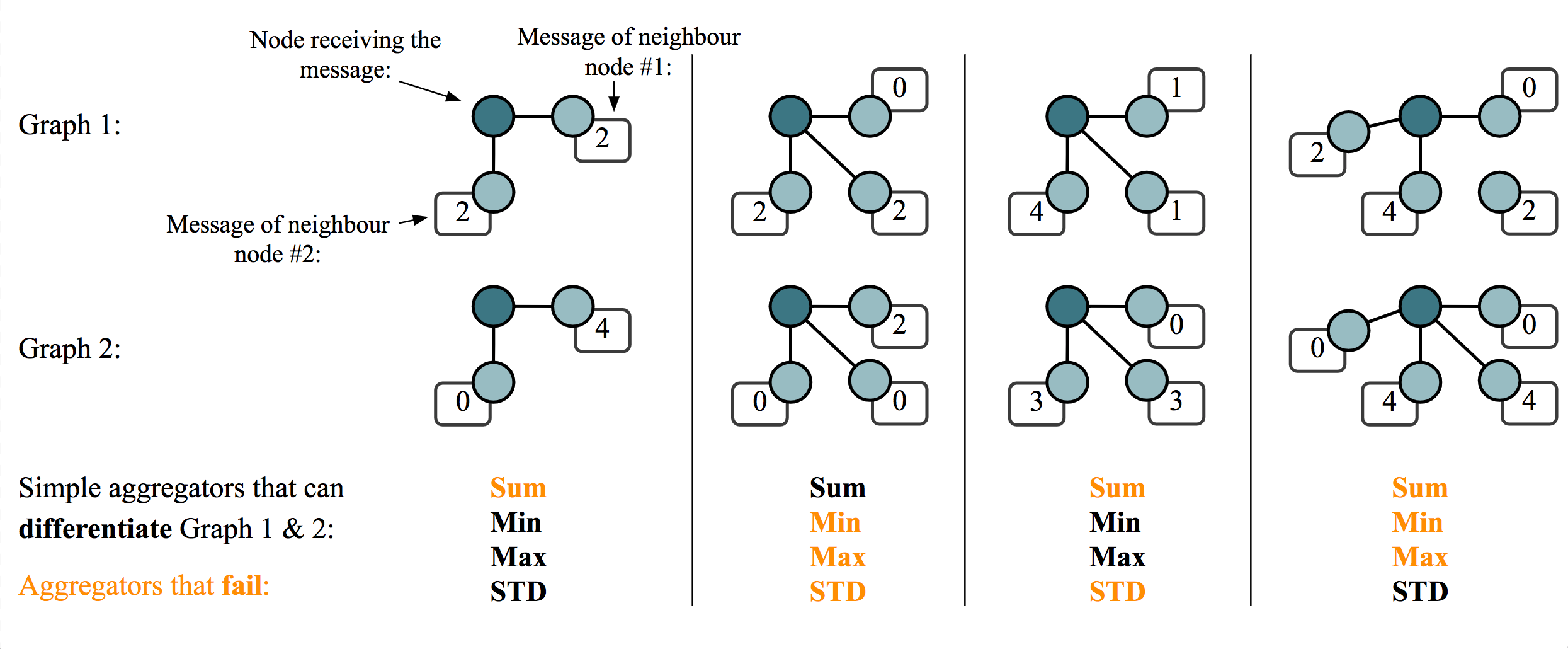

Several influential GNN papers were able to overcome this limitation. The first key development came from the graph isomorphism network (GIN)

In the multiset case, the framework from Deep Sets induces an additional constraint over \(\bigoplus\)—it needs to preserve the cardinality information about the repeated elements in a multiset. This immediately implies that some choices of \(\bigoplus\), such as \(\max\) or averaging, will not yield maximally powerful GNNs.

For example, consider the multisets $\{\mkern-4mu\{1, 1, 2, 2\} \mkern-4mu \}$ and $\{\mkern-4mu\{1, 2\}\mkern-4mu\}$. As we assume the features to be countable, we specify the numbers as one-hot integers; that is, \(1 = [1\ \ 0]\) and \(2=[0\ \ 1]\). The maximum of these features, taken over the multiset, is \([1\ \ 1]\), and their average is \(\left[\frac{1}{2}\ \ \frac{1}{2}\right]\). This is the case for both of these multisets, meaning that both maximising and averaging are incapable of telling them apart.

Summations \(\left(\bigoplus=\sum\right)\), however, are an example of a suitable injective operator.

Very similarly to the analysis from Wagstaff et al. in the domain of sets, a similar extension in the domain of graphs came through the work on principal neighbourhood aggregation by Corso, Cavalleri et al.

In fact, PNA itself is based on a proof that it is impossible to build an injective function over multisets with real-valued features using any single aggregator. In general, for an injective function over \(n\) neighbours, we need at least \(n\) aggregation functions (applied in parallel). PNA then builds an empirically powerful aggregator combination, leveraging this insight while trying to preserve numerical stability.

Note that there is an apparent similarity between these results and the ones from Wagstaff et al. 2019

There are also major differences between the two analyses: Wagstaff et al. 2019

In other words, it appears that potent processing of real-valued collections necessitates representational capacity proportional to the collection’s size, in order to guarantee injectivity. Discovering this correspondence is actually what brought the two of us together to publish this blog post in the first place.

We have now established what is necessary to create a maximally-powerful GNN over both countable and uncountable input features. So, how powerful are they, exactly?

The Weisfeiler-Lehman Test

While GNNs are often a powerful tool for processing graph data in the real world, they also won’t solve all tasks specified on a graph accurately! As a simple counterexample, consider any NP-hard problem, such as the Travelling Salesperson Problem. If we had a fixed-depth GNN that perfectly solves such a problem, we would have shown P=NP! Expectedly, not all GNNs will be equally good at solving various problems, and we may be highly interested in characterising their expressive power.

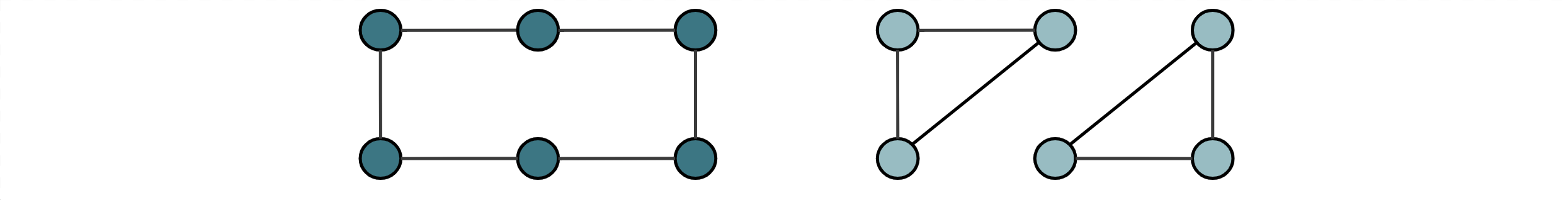

The canonical example for characterising expressive power is deciding graph isomorphism; that is, can our GNN distinguish two non-isomorphic graphs? Specifically, if our GNN is capable of computing graph-level representations \(\mathbf{h}_{\mathcal{G}}\), we are interested whether \(\mathbf{h}_{\mathcal{G_{1}}} \neq\mathbf{h}_{\mathcal{G_{2}}}\) for non-isomorphic graphs \(\mathcal{G}_{1}\) and \(\mathcal{G}_{2}\). If we cannot attach different representations to these two graphs, any kind of task requiring us to classify them differently is hopeless! This motivates assessing the power of GNNs by which graphs they are able to distinguish.

A typical way in which this is formalised is by using the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) graph isomorphism test. To formalise this, we will study a popular algorithm for approximately deciding graph isomorphism.

The WL algorithm featurises a graph \(\mathcal{G}=(\mathcal{V},\mathcal{E})\) as follows. First, we set the representation of each node \(i\in\mathcal{V}\) as \(x_i^{(0)} = 1\). Then, it proceeds as follows:

- Let $\mathcal{X}_i^{(t+1)} = \{\mkern-4mu\{x_j^{(t)} :(i,j)\in\mathcal{E}\}\mkern-4mu\}$ be the multiset of features of all neighbours of \(i\).

- Then, let \(x_i^{(t+1)}=\sum\limits_{y_j\in\mathcal{X}_i^{(t+1)}}\phi(y_j)\), where \(\phi : \mathbb{Q}\rightarrow\mathbb{Q}\) is an injective hash function.

This process continues as long as the histogram of \(x_i^{(t)}\) changes—initially, all nodes have the same representation. As steps 1–2 are iterated, certain \(x_i^{(t)}\) values may become different. Finally, the WL test checks whether two graphs are (possibly) isomorphic by checking whether their histograms have the same (sorted) shape upon convergence.

While remarkably simple, the WL test can accurately distinguish most graphs of real-world interest. It does have some rather painful failure modes, though; for example, it cannot distinguish a 6-cycle from two triangles!

This is because, locally, all nodes look the same in these two graphs, and the histogram never changes.

The key behind the power of the WL test is the injectivity of the hash function \(\phi\)—it may be interpreted as assigning each node a different colour if it has a different local context. Similarly, we saw that GNNs are maximally powerful when their propagation models are injective. It should come as little surprise then that, in terms of distinguishing graph structures over countable input features, GNNs can never be more powerful than the WL test! And, in fact, this level of power is achieved exactly when the aggregator is injective. This fact was first discovered by Morris et al.

While the WL connection has certainly spurred a vast amount of works on improving GNN expressivity, it is also worth recalling the initial assumption: \(x_i^{(0)} = 1\). That is, we assume that the input node features are completely uninformative! Very often, this is not a good idea! It can be proven that even placing random numbers in the nodes can yield to a provable improvement in expressive power (Sato et al.

Even beyond the limitation of the uninformative input features, recent influential works (published at ICLR’22 and ‘23 as orals) have demonstrated that the WL framework itself is worth extending. Geerts and Reutter

Lastly, linking back to our central discussion, we argue that focusing the theoretical analysis only on discrete features may not lead to highly learnable target mappings. From the perspective of the WL test (and basically any discrete-valued procedure), the models presented in Deep Sets and PNA are no more powerful than 1-WL. However, moving into continuous feature support, PNA is indeed more powerful at distinguishing graphs than models like GIN.

Broader Context and Takeaways

It is no coincidence that many of the current universality discussions within machine learning are happening inside communities that build networks that exploit symmetries (in our examples, the symmetry was always permutation invariance/equivariance, but the following argument equally applies to, e.g., rotational symmetries): exploiting symmetries with a neural network architecture is tantamount to limiting the space of functions that can be learned. This naturally raises the question of how much the space of learnable function has been limited. In other words: for the space of functions observing a specific symmmetry, is the neural network (still) a universal function approximator? This does not imply, however, that universality isn’t interesting in other fields, too: e.g., the fact that self-attention (popularised by natural language processing) is a universal approximator for functions on sets is an interesting property that gives its design more context. The (once) ubiquitous usage of the convolutional layer seems less surprising when knowing that it is the most general

In this blog post, we aimed at explaining most of the key concepts of universal function approximation for set and graph-based machine learning: invariance and equivariance, sets and multisets, representation vs. approximation, injectivity, Deep Sets, GINs, WL-tests, and the motivation for universality research itself. We hope that we provided some insights into the similarities and differences of universality research on graphs and sets, and maybe even food for thought leading to future research on this intersection. We also acknowledge that this is a theoretical topic and that none of these proofs can ultimately predict how well a ‘universal’ neural network will perform on a specific task in the real world. However, even in the worst-case scenario, where theoretical universality properties are completely uncorrelated (or inversely correlated?) with real-world performance, we still hope that the thoughts and concepts of this post add a bit of additional structure to the multifaceted zoo of neural network architectures for sets and graphs.