A Match Made in Drug Discovery - Marrying Geometric and Diffusion Models

The chemical space of molecular candidates is vast, and within this space, interesting and powerful drugs are waiting to be found. The use of machine learning has shown to be an effective method to speed up the process of discovering novel compounds, especially the use of (deep) generative models. The recent surge in graph generative models have opened up new avenues for exploring the chemical space of molecular candidates, enabling a more efficient and systematic exploration of the chemical space, increasing the chances of finding novel and potent molecules. One of the recent breakthroughs includes the use of diffusion models, which have proven to yield superior performance in molecular conformation tasks, among others. In this blog post, we aim to highlight one of them, which is the 'GeoDiff - A Geometric Diffusion Model for Molecular Conformation Generation' paper by Xu et al. (2022). We aim to distill the paper in semi-layman terms, to provide researchers and practitioners with a deeper understanding of the (i) methodology and results and (ii) (societal) implications of this breakthrough in the field of drug discovery and (iii) discuss future applications in the field of (bio)medicine.

A Match Made in Drug Discovery: Marrying Geometric and Diffusion Models

Introduction

With the initial breakthrough of the Denoising Diffusion

Data-driven applications have increasingly been shown to accelerate solving diverse problems in the drug discovery pipeline

Motivation

Generating molecular conformations is a task fundamental to cheminformatics and drug discovery. The conformation of a molecule refers to the three-dimensional (3D) coordinates of all the atoms in a molecule in a 3D Euclidean space, which can be interconverted by rotations about formally single bonds

Therefore, we are only interested in conformations that fall in stable low-energy minima, as these low-energy conformations are the ones that the molecule will most likely adopt under natural conditions and play a crucial role in determining the molecule’s behaviour and properties. By identifying and characterizing the low-energy conformations, researchers gain insights into their stability, reactivity and interactions with other molecules.

Formulating the conformation generation problem

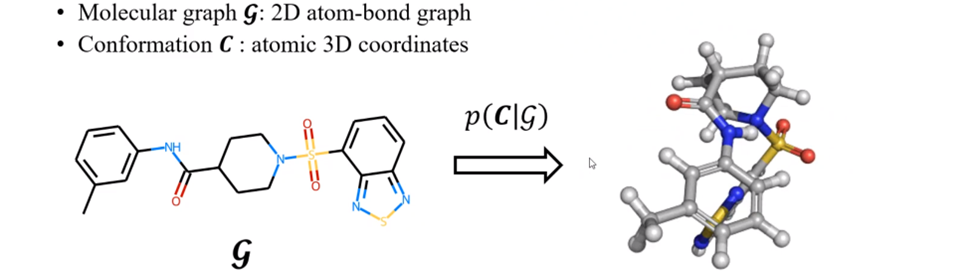

A formulation of the conformation generation problem, adapted from

| We can formulate the problem of conformation generation as a conditional generative problem where we aim to generate stable conformations \(C\) from a molecule’s graph \(G\). For each \(G\) given its conformations \(C\) as i.i.d samples from an underlying Boltzmann distribution | G)$$ to draw possible conformations from. |

Roto-translation equivariance

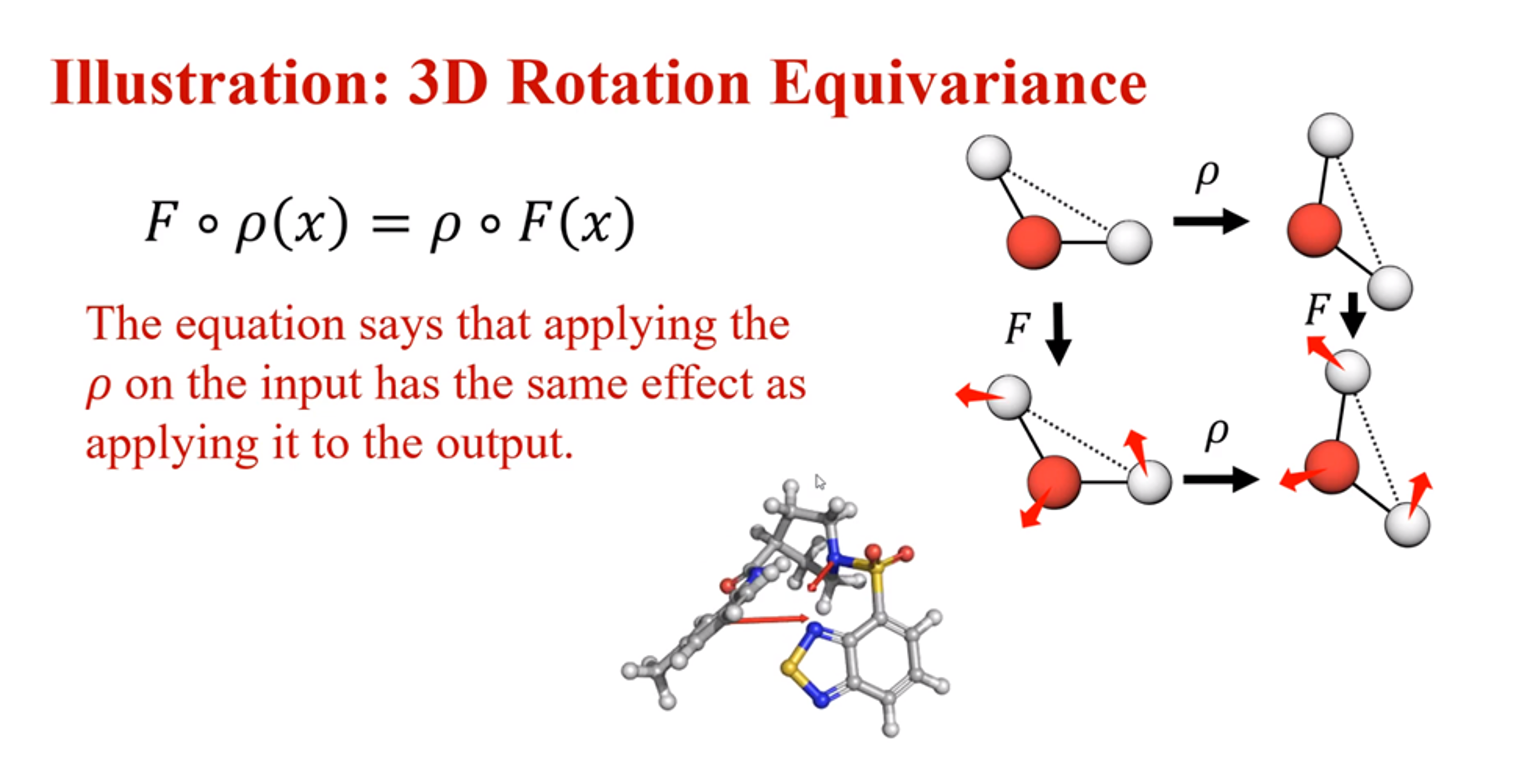

A visualisation of roto-translation equivariance, adapted from

To generate stable molecular conformations, we need an algorithm that preserves roto-translation equivariance of the conformations that previous work has not focused on. To explain this property, let us delve into what equivariance is. A representation \(φ\) is equivariant with a transformation \(g\) of the input if the transformation can be transferred to the representation output. Invariance is a special case of equivariance obtained when the transformation is the identity map

In the context of molecular conformations, we have to achieve the special case of equivariance in terms of rotation and translation, namely, roto-translation equivariance of the conformations which ensures that however the molecule is rotated or translated, the estimated (conditional) likelihood should be unaffected. GeoDiff considers the SE(3) Lie group which can be used to represent rotation and translation in 3D space

Decomposing GeoDiff

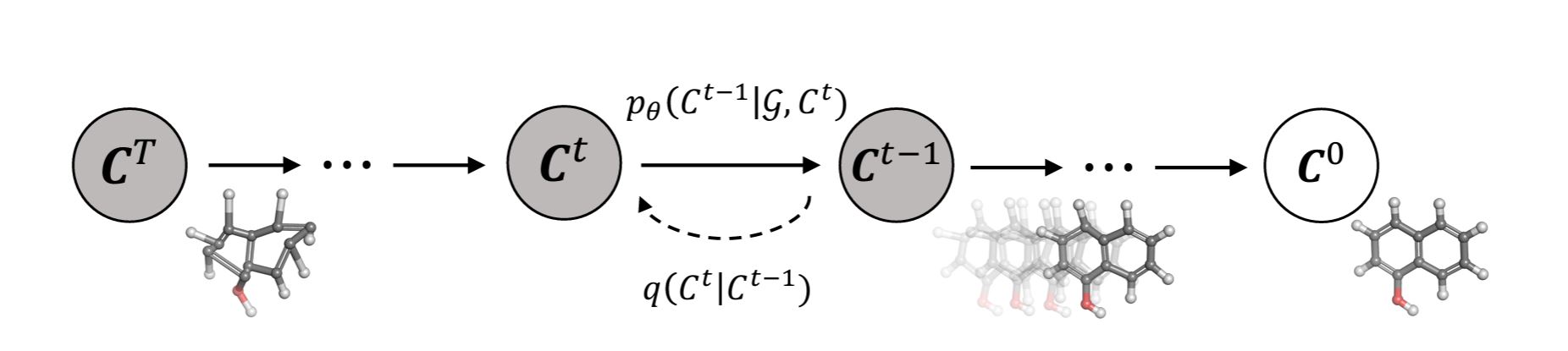

The diffusion model of GeoDiff, adapted from

Legend:

- \(C^{0}\) denotes the ground truth conformations

- \(C^{t}\), where \(t = 1,···, T\) is the index for diffusion steps and \(C^{t}\), is the sequence of latent variables with the same dimension

- \(q(C^{t} \mid C^{t-1})\) is the fixed posterior distribution

- \(p_\theta(C^{t-1} \mid G, C^{t})\) are the Markov kernels through which the conformations are refined

A primer on Diffusion Models

A diffusion probabilistic model

In this blog post, we use the GeoDiff implementation of diffusion models to explain how the diffusion model works and how it is being used for the geometric representation of molecules. The implementation of the diffusion model in GeoDiff is inspired by the DDPM paper

Forward process

Let \(q(\mathbf{C}^0)\) be the real data distribution of molecular conformation. We can sample from this distribution to get a conformation, \(\mathbf{C}^0 \sim q(\mathbf{C}^0)\). We define the forward diffusion process which adds Gaussian noise at each time step \(t\), according to a known variance schedule \beta_t which can be linear, quadratic, cosine, etc. as follows:

\[\begin{align}\tag{1} q\left(\mathcal{C}^{1: T} \mid \mathcal{C}^0\right)=\prod_{t=1}^T q\left(\mathcal{C}^t \mid \mathcal{C}^{t-1}\right) \end{align}\]where \(\quad q\left(\mathcal{C}^t \mid \mathcal{C}^{t-1}\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathcal{C}^t ; \sqrt{1-\beta_t} \mathcal{C}^{t-1}, \beta_t I\right)\)

Instead of having to compute \(q\left(\mathcal{C}^t \mid \mathcal{C}^{t-1}\right)\) at every timestep \(t\), we could compute at an arbitrary timestep in closed form:

\[\begin{equation}\tag{2} q\left(\mathcal{C}^t \mid \mathcal{C}^0\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathcal{C}^t ; \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathcal{C}^0,\left(1-\bar{\alpha}_t\right) I\right) \end{equation}\]where \(\alpha_t=1-\beta_t\) and \(\bar{\alpha}_t=\prod_{s=1}^t \alpha_s\)

Thus with a sufficiently large number of timesteps, the forward process could convert \(\mathcal{C}^0\) to whitened isotropic Gaussian and so we could set \(p\left(\mathcal{C}^T\right)\) as a standard Gaussian distribution.

Reverse Process

The reverse process involved recovering the original conformation \(\mathcal{C}^0\) from the white noise \(\mathcal{C}^T\) . We need the conditional distribution \(p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t\right)\) to sample some random Gaussian noise \(\mathcal{C}^t\), and “denoise” gradually to end up with a sample from the real distribution \(\mathcal{C}^0\).

However, the conditional distribution of \(p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t\right)\) is intractable as it requires knowing the distribution of all possible conformations in order to calculate this conditional probability. Hence, a neural network could be used to learn this conditional probability distribution, let’s call it \(p_\theta\), with \(\theta\) being the parameters of the neural network, updated by gradient descent. Thus, we formulate the reverse process as a conditional Markov chain with learnable transitions:

\[\begin{align*}\tag{3} p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{0: T-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^T\right)=\prod_{t=1}^T p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t\right) \end{align*}\]where \(\quad p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t\right)=\mathcal{N}\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} ; \mu_\theta\left(\mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t, t\right), \sigma_t^2 I\right)\)

Hence, the neural network in the reverse process needs to learn/represent the mean and variance. However, just like the DDPM paper, GeoDiff also lets the variance be user-defined and fixed, and \(\mu_\theta\) is the neural network that estimates means.

GeoDiff uses a parametrisation trick inspired by the diffusion model implementation from the DDPM paper such that this parametrisation resembles Langevin dynamics and simplifies the diffusion model’s variational bound to an objective that resembles denoising score matching. Moreover, in the context of molecular conformation generation, this parametrisation trick is analogous to the physical force fields

where \(\epsilon_\theta\) are neural networks with trainable parameters \(\theta\).

Now, we need to make \(\epsilon_\theta\) roto-translational equivariant which we elaborate on in the next section.

Making the reverse process roto-translation equivariant

Firstly, we need to assume the prior distribution of the conformations and the intermediary conformations generated during the forward process are systems with zero centre of mass (CoM) or CoM-free systems

GeoDiff employs the use of an equivariant convolutional layer, named graph field network (GFN) inspired by

where

- \(\Phi\) are feed-forward networks

- \(d_{ij}\) are interatomic distances

- \(\mathcal{N}(i)\) is the neighbourhood of the \(i\)-th node, which consists of both connected atoms and other ones within a radius threshold \(\tau\).

By introducing the neighbourhood function, we enable the model to accurately represent distant interactions between atoms, as well as the ability to handle partially disconnected molecular graphs. Initial embeddings \(h_0\) are combinations of atom and timestep embeddings, and \(x_0\) are atomic coordinates. A key change in GFN compared to a vanilla GNN is \(x\) being updated as a combination of radial directions weighted by \(\Phi_x\): \(\mathbb{R}^b \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) as seen in equation \((7)\). This allows the roto-translation equivariance property to be induced in the reverse process.

Improved Training Objective

Now, we need to set the training objective having considered the reverse process dynamics. We cannot compute the exact log-likelihood of the generative process, as it involves computing the likelihood of the observed molecular conformation given the parameters of the model. However, this likelihood is difficult to compute, as it would require integrating over all possible intermediate conformations, giving us a high-dimensional integral that cannot be solved analytically. Therefore, the authors have opted to maximize the variational lower bound (ELBO), as defined below:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\log p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^0 \mid \mathcal{G}\right)\right] & =\mathbb{E}\left[\log \mathbb{E}_{q\left(\mathcal{C}^{1: T} \mid \mathcal{C}^0\right)} \frac{p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{0: T} \mid \mathcal{G}\right)}{q\left(\mathcal{C}^{1: T} \mid \mathcal{C}^0\right)}\right] \\ & \geq-\mathbb{E}_q\left[\sum_{t=1}^T D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{C}^t, \mathcal{C}^0\right) \| p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{C}^t, \mathcal{G}\right)\right)\right]:=-\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{ELBO}}\end{aligned}\]where \(q\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{C}^t, \mathcal{C}^0\right)\) is analytically tractable as \(\mathcal{N}\left(\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \beta_t}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathcal{C}^0+\frac{\sqrt{\alpha_t}\left(1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}\right)}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathcal{C}^t, \frac{1-\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \beta_t\right)\).

Using the parametrisation trick in the reverse process as seen in equation \((4)\), the ELBO could be simplified by taking the KL divergences between Gaussians as weighted \(\mathcal{L}_2\) distances between the means \(\epsilon_\theta\) and \(\epsilon^3\) as follows: \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{ELBO}}=\sum_{t=1}^T \gamma_t \mathbb{E}_{\left\{\mathcal{C}^0, \mathcal{G}\right\} \sim q\left(\mathcal{C}^0, \mathcal{G}\right), \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)}\left[\left\|\epsilon-\epsilon_\theta\left(\mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t, t\right)\right\|_2^2\right]\) where \(\mathcal{C}^t=\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathcal{C}^0+\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon\).

The idea behind this objective is to independently sample chaotic conformations of different timesteps from \(q\left(C^{t-1} \mid C^t, C^0\right)\), and use \(\epsilon_\theta\) to approximate the noise vector \(\epsilon\).

Sampling

Now, we can generate stable molecular conformations via sampling. Given a graph \(\mathcal{G}\), its geometry \(\mathcal{C}^0\) is generated by first sampling chaotic particles \(\mathcal{C}^T \sim p\left(\mathcal{C}^T\right)\). For each timestep in the reverse process \(t=T, T-\) \(1, \cdots, 1\), we first shift the CoM of the conformation to zero, compute the transition means, \(\mu_\theta\left(\mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t, t\right)\), using equation \((4)\) and sample \(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \sim\) \(p_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{t-1} \mid \mathcal{G}, \mathcal{C}^t\right)\). The sampling algorithm is given in pseudo-code below:

| Algorithm 1 Sampling Algorithm of GEODIFF |

|---|

| Input: the molecular graph \(\mathcal{G}\), the learned reverse model \(\epsilon_\theta\). |

| Output: the molecular conformation \(\mathcal{C}\). |

| 1: Sample \(\mathcal{C}^T \sim p\left(\mathcal{C}^T\right)=\mathcal{N}(0, I)\) |

| 2: for \(s=T, T-1, \cdots, 1\) do |

| 3: \(\quad\) Shift \(\mathcal{C}^s\) to zero CoM |

| 4: \(\quad\) Compute \(\mu_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^s, \mathcal{G}, s\right)\) from \(\epsilon_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^s, \mathcal{G}, s\right)\) using equation 4 |

| 5: \(\quad\) Sample \(\mathcal{C}^{s-1} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mathcal{C}^{s-1} ; \mu_\theta\left(\mathcal{C}^{\mathcal{s}}, \mathcal{G}, s\right), \sigma_t^2 I\right)\) |

| 6: end for |

| 7: return \(\mathcal{C}^0\) as $\mathcal{C}$$ |

But why generative models?

The purpose of prediciting molecular conformations is to enable human experts to analyse the properties of the molecules and understand how these properties affect the viability of a molecule as a drug candidate. Therefore, it is important that the molecular conformations generated are diverse to capture the different possible conformations that could occur in nature but the conformations generated should not deviate significantly such that the analysis is affected. To set a threshold for the different possible conformations, the standard metric used has been selecting conformations that are within a certain root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), say a few ångströms, of the true structure.

However, the objective of maximizing the proportion of predictions with RMSD within some tolerance \(\epsilon\) is not differentiable and thus, cannot be used for training with stochastic gradient descent. Instead, maximizing the expected proportion of predictions with RMSD < \(\epsilon\) corresponds to maximizing the likelihood of the true structure under the model’s output distribution, in the limit as \(\epsilon\) goes to 0. This concept inspires the development of a generative model, whose objective is to minimize an upper bound on the negative log-likelihood of observed molecular structures under the distribution of the model. As a result, the problem of molecular docking is treated as a task of learning a distribution over possible positions of a ligand molecule conditioned on the protein structure and a diffusion generative model is developed to represent this space. Therefore, this observation has motivated several works on the use of generative models for molecular conformation generation, such as GeoDiff.

Future work

While diffusion models have shown promising results over the past months, there is still a need for further research and development to address some of the limitations and drawbacks of the use of diffusion models in conformer generation. As explained in our blog post, generative models are well-suited for molecular conformation generation. However, there are other kinds of established generative models, such as autoencoders that have been used for the same task

It must be noted that the experiments described in the study are done on benchmark geometric datasets, GEOM-QM9

GeoDiff as a framework sets a precedent for future work that could marry the concepts of geometric deep learning and diffusion models across various domains. In the context of drug discovery, it would be interesting to extend this framework to more challenging structures, such as proteins, which may enable more accurate prediction of protein folding, protein-protein interactions and protein-ligand binding positions which would facilitate the design of new drugs and treatments. Additionally, this framework could potentially be applied to other complex systems beyond proteins, such as RNA molecules, to enable more efficient and accurate prediction of their behaviour and properties. Continued research in this area has the potential to revolutionize drug discovery and development, as well as advance our understanding of the fundamental principles governing the behaviour of complex biological systems.

Research on the application of diffusion models in the life and natural sciences is still in its infancy, with great potential for improvement in terms of both theory as well as empirical testing. The GeoDiff model could be improved in terms of more efficient sampling and improved likelihood maximization methods. Traditionally, generating samples from diffusion models demand iterative approaches that involve a large number of evaluation steps. Recent work, such as the paper on Torsional Diffusion

Looking ahead, GeoDiff has set a clear example for the use of diffusion models on geometric representations which could be extended to several problems, especially in the field of drug discovery. The novel contributions made by

are motivated by the physical characteristics of the molecular conformation generation problem, which has resulted in a strong candidate method for conformation generation that could act as a springboard for even more effective and efficient methods that would eventually benefit the field of drug discovery as a whole.