Building Blocks of Text-to-Video Generation

Google's Imagen Video and Meta's Make-a-Video Explained

Google’s Imagen Video and Meta’s Make-a-Video Explained

In this post, we dissect and explain the mechanics behind the key building blocks for state-of-the-art Text-to-Video generation. We provide interactive examples of these building blocks and demonstrate the key novelties/differences between two Text-to-Video models: Imagen Video and Make-a-Video. Finally, we summarize by showing how the building blocks fit together into a complete Text-to-Video framework as well as noting the current failure modes and limitations of the models today.

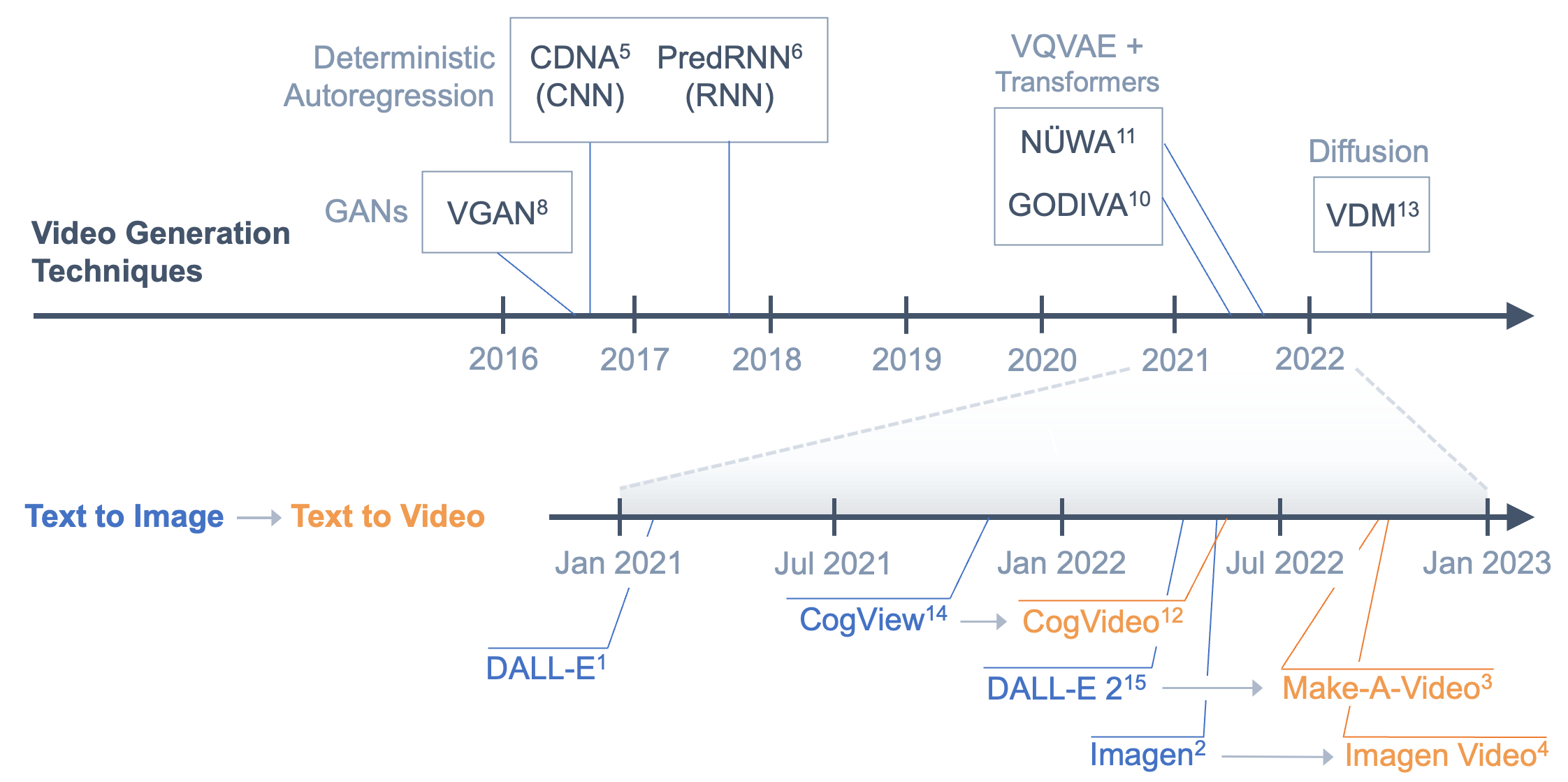

History of Text-to-Video

Just six months after the release of DALL-E 2, both Meta and Google released novel Text-to-Video generation models that output impressive video-format content. These networks build off of recent advancements in Text-to-Image modeling using stable diffusion (like DALL-E [1] and Imagen [2]). Meta’s Make-A-Video [3] is capable of five second 768x768 clips at variable frame rates while Google’s Imagen Video [4] can produce 1280×768 videos at 24 fps. Rather than training strictly on text-video pair datasets, both Imagen Video and Make-a-Video leverage the massive text-image pair databases to construct video from pretrained Text-to-Image generation models. These Text-to-Video generators are capable of creating high-resolution, photorealistic and stylistic content of impossible scenarios. Networks such as these can be powerful tools for artists and creators as well as the basis for predicting future frames of a video.

Video generation has progressed rapidly in the past decade. Early video generation models focused on simple, specific domains and next frame prediction with deterministic autoregressive methods (CDNA [5], PredRNN [6]). Later video prediction models incorporated stochasticity (SV2P [7]). Another line of work uses generative models, namely GANs, to synthesize complex scenes without a first frame (VGAN [8], TGAN [9]). More recently, Text-to-Video has been approached with VQVAEs to learn latent representations of video frames and then autoregressive transformers to generate video samples (GODIVA [10], NUWA [11]). This technique allows for open-domain video generation, but frames are still generated one at a time chronologically, resulting in potentially poor text-video alignment. CogVideo [12] adjusts the training procedure to fix alignment (discussed below) and uses pre-trained Text-to-Image weights. Make-A-Video and Imagen Video both use diffusion models (VDM [13]), which we will discuss in the next section.

Make-A-Video and Imagen Video have come out just six months after Open-AI’s DALL-E 2. Text-to-Video is a much harder problem than Text-to-Image because we don’t have access to as many labeled text-video pairs. Therefore, all the models we highlight take advantage of starting from an existing Text-to-Image model with pre-trained or frozen weights. Moreover, beyond just generating pixels, the network has to predict how they will all evolve over time to coherently complete any actions in the text prompt.

We’ll break down the building blocks to make Text-to-Video generation possible, starting from a brief overview of how Text-to-Image generators use stable diffusion, how to make the components 3D to incorporate temporal information for video generation, and how to increase the spatial and temporal resolution. We focus on how these components make up Make-A-Video and Imagen Video, but also touch on CogVideo (an open-source Text-to-Image video generator that uses a VQVAE + autoregressive transformers architecture).

Text-to-Image Generation

What is latent space?

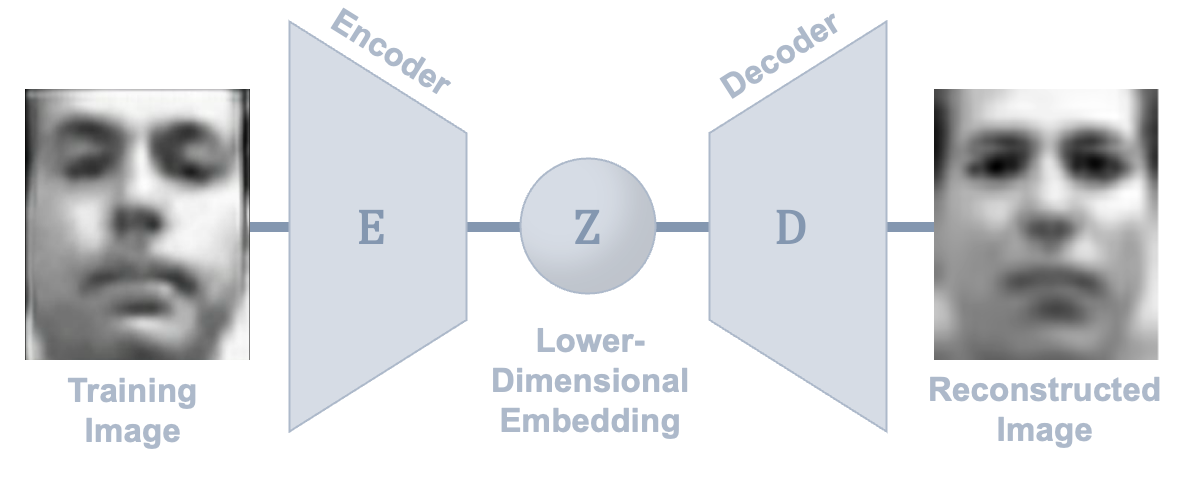

Text-to-Image generation uses stable diffusion in latent space and a 2D U-Net architecture for image generation (see link for more details). First let’s explain how auto-encoders work:

Here an input image is encoded into a lower-dimensional latent space representation and a decoder can reconstruct the image. This network is trained on the Frey Faces Dataset by comparing the input to the reconstructed output. Sampling within the latent space distribution allows us to generate realistic outputs.

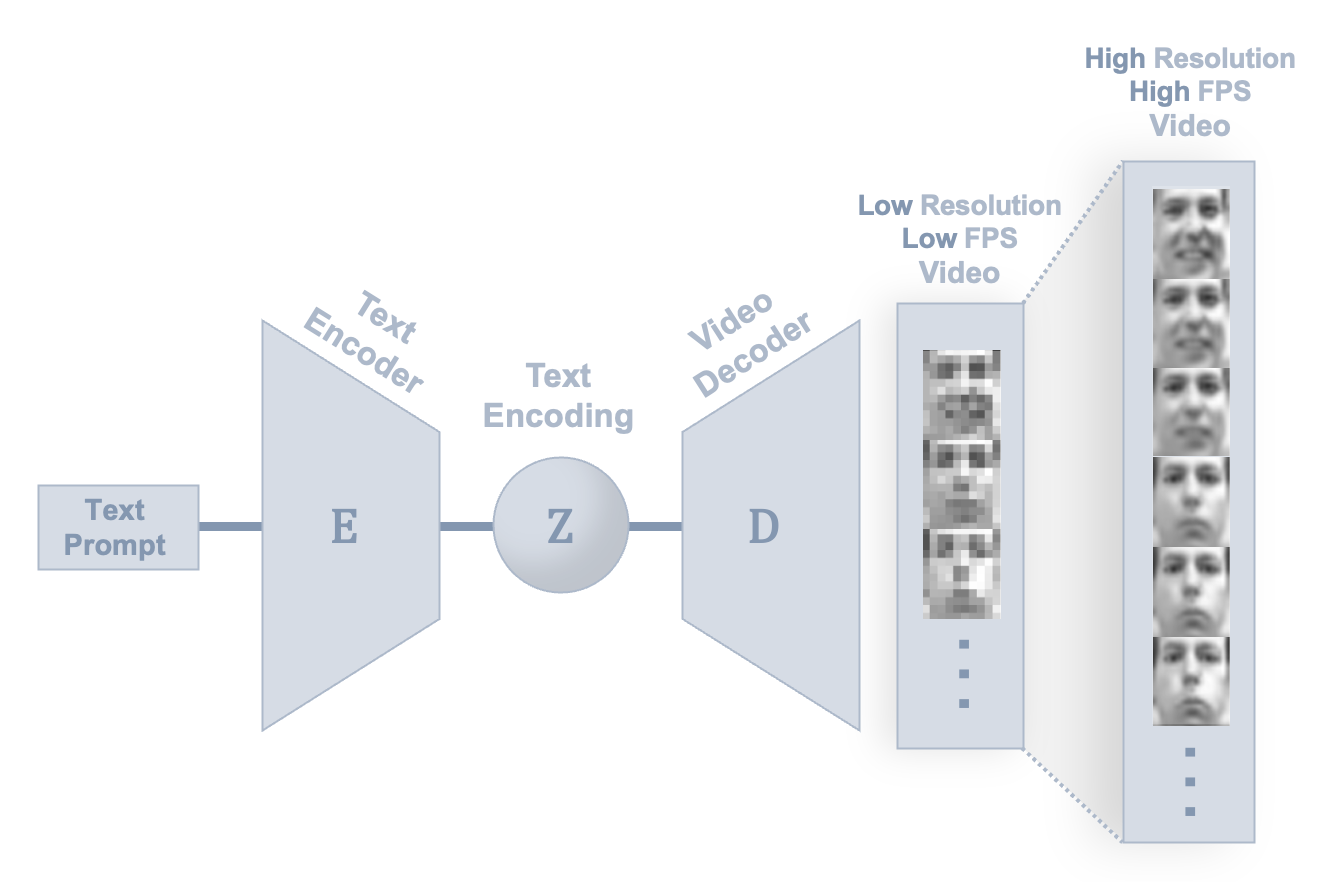

For Text-to-Video generation, the encoding-decoding network is trained using stable diffusion [15].

How does stable diffusion work in latent space?

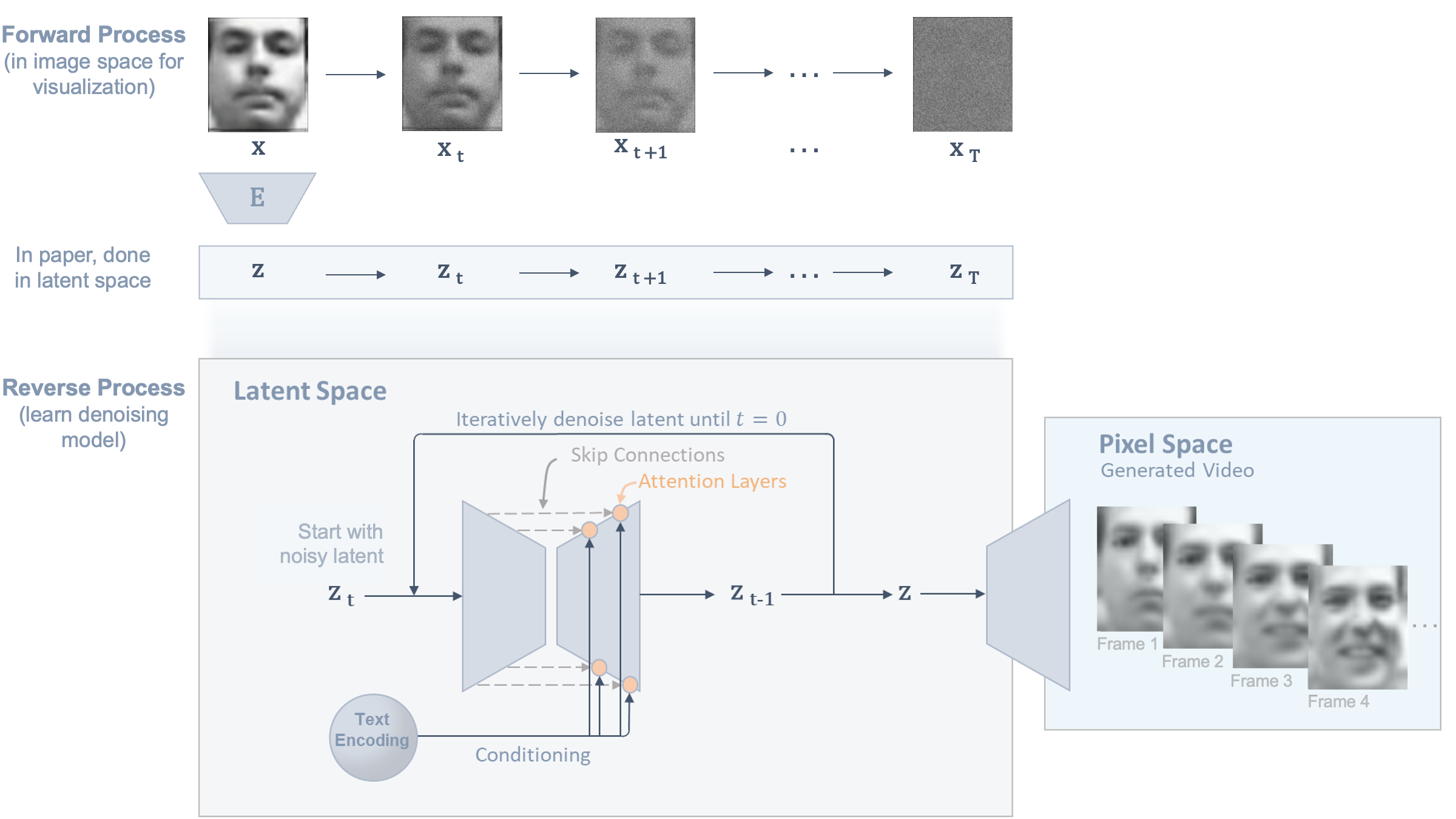

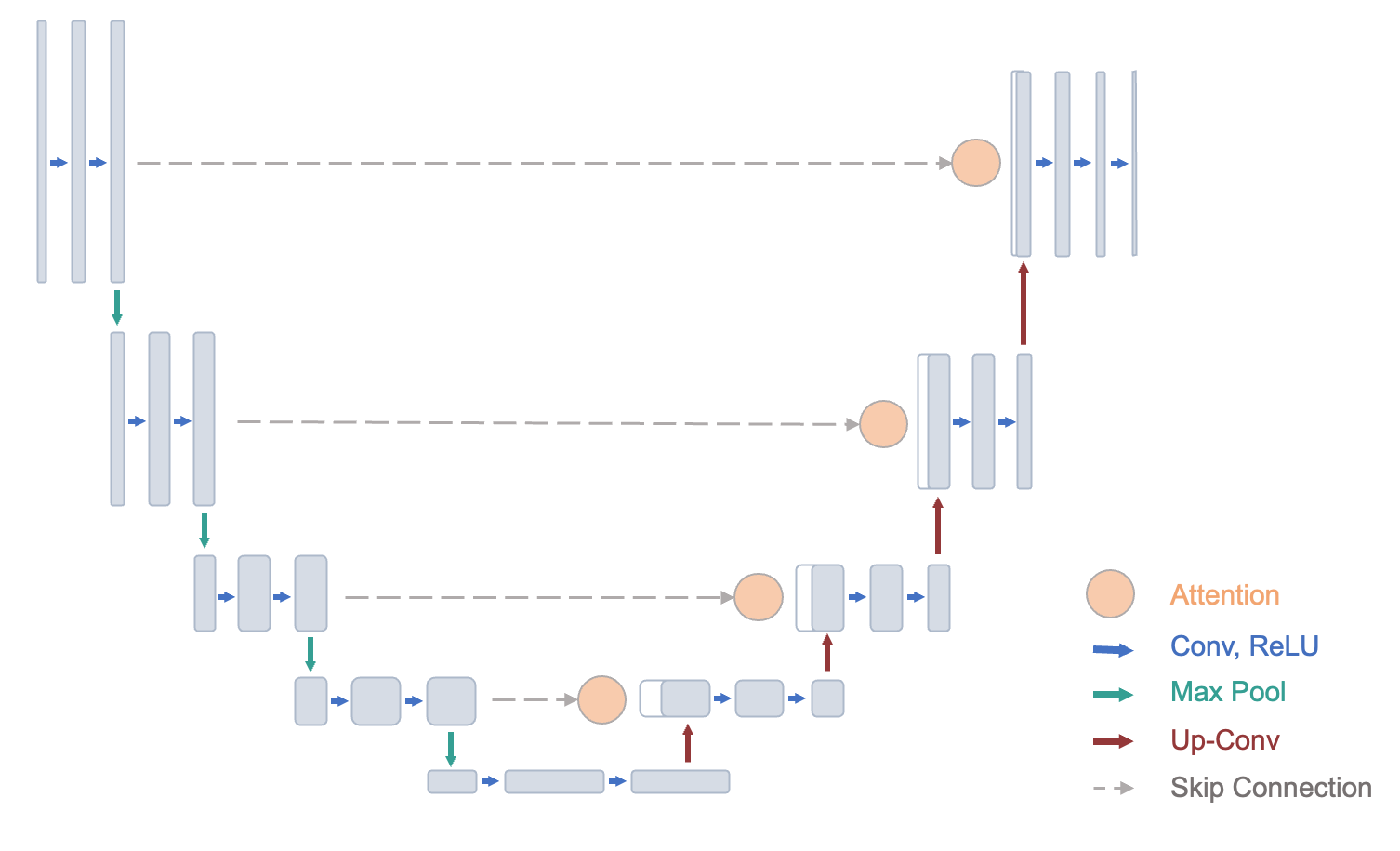

During the forward process, we create a dataset by incrementally adding more noise to our latent variables. In the reverse process, we train a model with a U-Net architecture [16] to iteratively denoise these latents. This way, we can efficiently generate new images by starting with random noise and end up with a latent that can be decoded into a real image (while conditioning layers on the input text embedding).

The U-Net architecture (which we use as a noise detector) is an autoencoder. Downsampling and upsampling is done with convolutional layers. However, because the latent space is lower-dimensional, it’s possible to lose information, meaning that spatial recreation can be imprecise during upsampling. To deal with this, U-Net has skip connections that transfer information across the network, bypassing the downsampling and compression.

However, the poor feature representation in the initial layers result in redundant information. To deal with this, we can add attention layers at the skip connections to suppress activation in irrelevant regions, reducing the number of redundant features brought across by focusing “attention” only on the most important image features. For Text-to-Image generation, these attention networks also have access to the text embeddings to help condition the attention.

In the next section we discuss how to modify our convolutional and attention layers to move from image (2D spatial) representations to video (3D) representations, composed of individual frames (2D spatial) + time (1D temporal).

Text-to-Video Generation

How do we extend Text-to-Image to Text-to-Video?

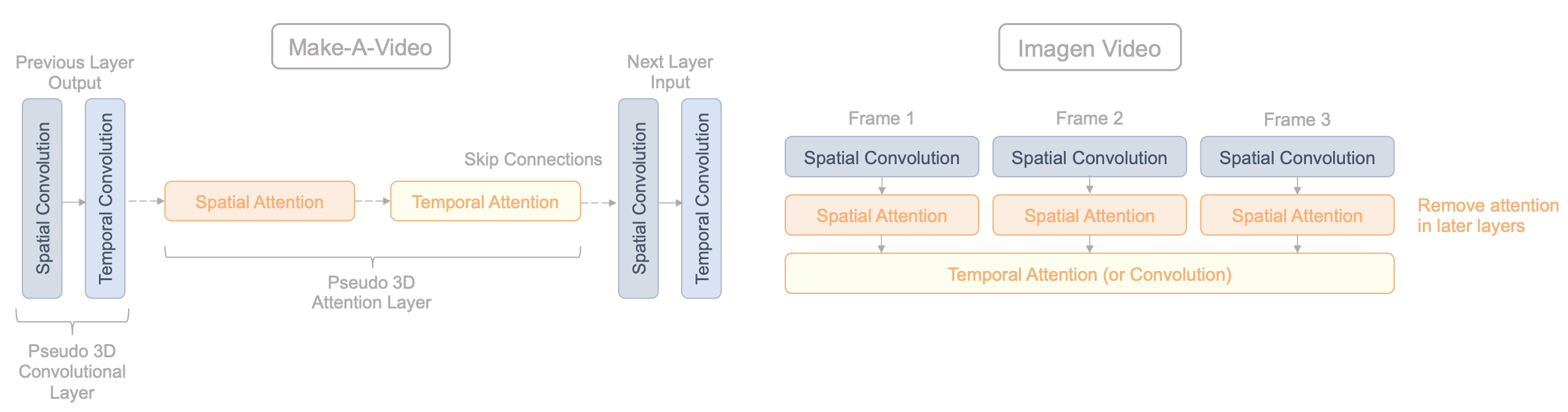

Text-to-Image generation uses U-Net architecture with 2D spatial convolution and attention layers. For video generation, we need to add a third temporal dimension to the two spatial ones. 3D convolution layers are computationally expensive and 3D attention layers are computationally intractable. Therefore, these papers have their own approaches.

Make-A-Video creates pseudo 3D convolution and attention layers by stacking a 1D temporal layer over a 2D spatial layer. Imagen Video does spatial convolution and attention for each individual frame, then does temporal attention or convolution across all frames.

Separating the spatial and temporal operations allows for building off of existing Text-to-Image models.

- CogVideo freezes all the weights of the spatial layers

- Make-A-Video uses pretrained weights for the spatial layers but initializes the temporal layer weights to the identity matrix. This way they can continue tuning all weights with new video data

- Imagen Video can jointly train their model with video and image data, doing the latter by masking the temporal connections

Spatial and Temporal Super Resolution

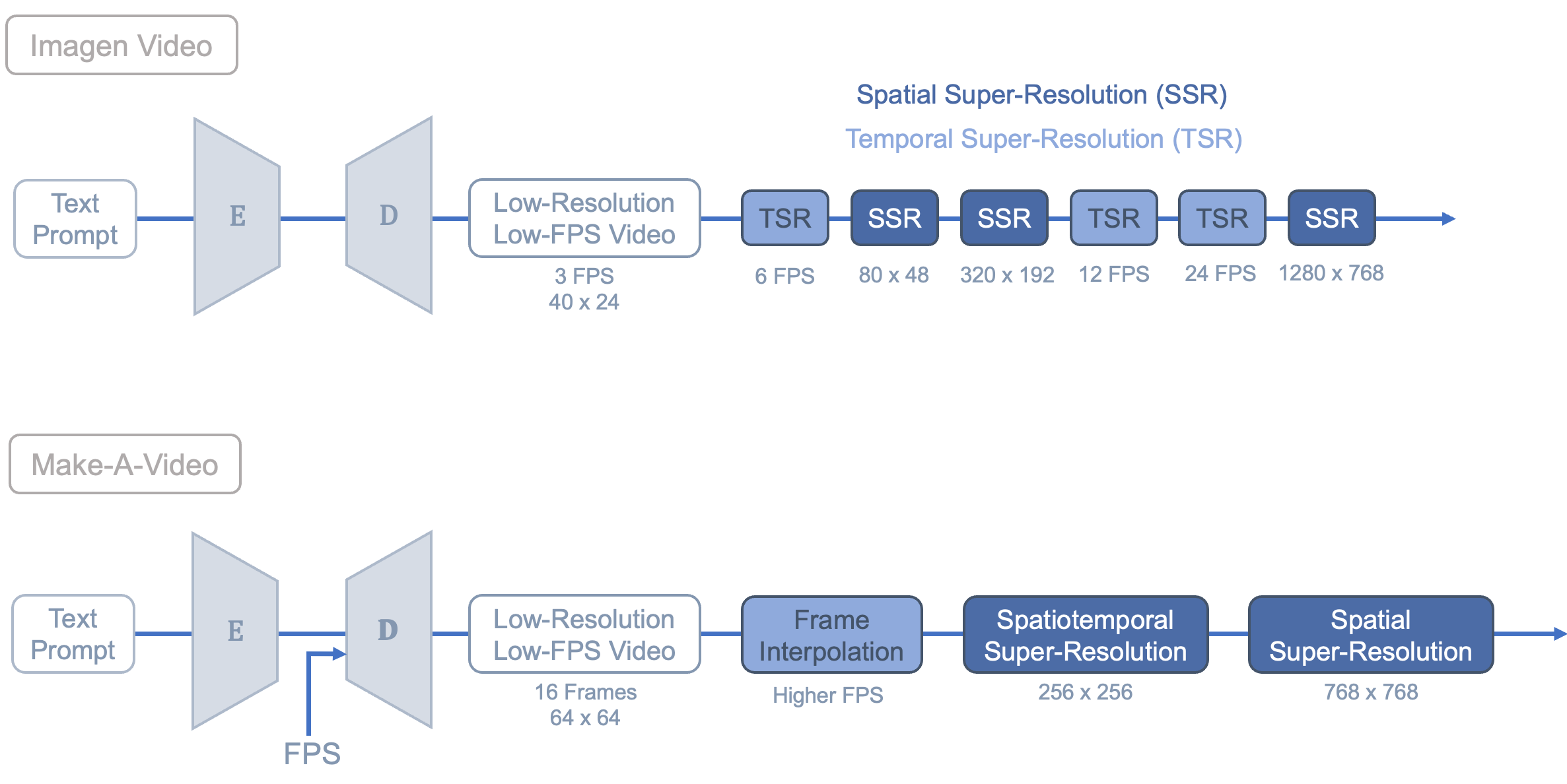

The base video decoder creates a fixed number of frames (5 frames for CogVideo, 16 frames for Make-A-Video, and 15 frames for Imagen Video) that need to be upsampled temporally and spatially.

Make-A-Video uses frame rate conditioning, meaning they have an additional input that determines the fps in the generated video (unlike how Imagen Video has a fixed frame rate in each stage). During training, this is useful as a form of data augmentation due to the limited dataset of videos. CogVideo also highlights the importance of changing the frame rate in order to retime videos such that an entire action can be encompassed in a fixed video length. For example the action “drinking” is composed of the sub-actions “pick up glass,” “drink,” and “place glass” which need to be performed in that order. If training on videos of a fixed length, changing the frame rate can help ensure text-video alignment.

Frame interpolation for Make-A-Video is done in an autoregressive manner. They fine-tune a spatio-temporal decoder by masking certain frames of a training video and learning to predict them. They train with variable frame-skips and fps conditioning to enable different temporal upsampling rates. The framework is also able to interpolate and extrapolate (extend the beginning or end of a video).

Imagen Video’s approach relies on cascaded video diffusion models. They generate entire blocks of frames simultaneously for each network to avoid the artifacts that would result from running super-resolution on independent frames. Each of the 6 super-resolution sub-models after the base video diffusion model, shown in Figure 7 (top), focuses on either temporal or spatial upsampling. While the base model (the video decoder at the lowest frame rate/resolution) uses a temporal attention layer to model long-term temporal dependencies, the super-resolution models only use temporal convolution layers for computational efficiency while still maintaining local temporal consistency. Similarly, spatial attention is only used in the base and first two spatial super-resolution models, while the rest only use convolution.

Make-A-Video’s approach initially interpolates frames and then increases the spatial resolution with two super-resolution layers, shown in Figure 7 (bottom). The first super-resolution layer operates across spatial and temporal dimensions. The second super-resolution layer only operates across the spatial dimension because of memory and space constraints. However, spatial upsampling requires detail hallucination which needs to be consistent across frames (hence the use of the temporal dimension in the previous layer). To deal with this, they use the same noise initialization for each frame to encourage consistent detail hallucination across frames.

Conclusions

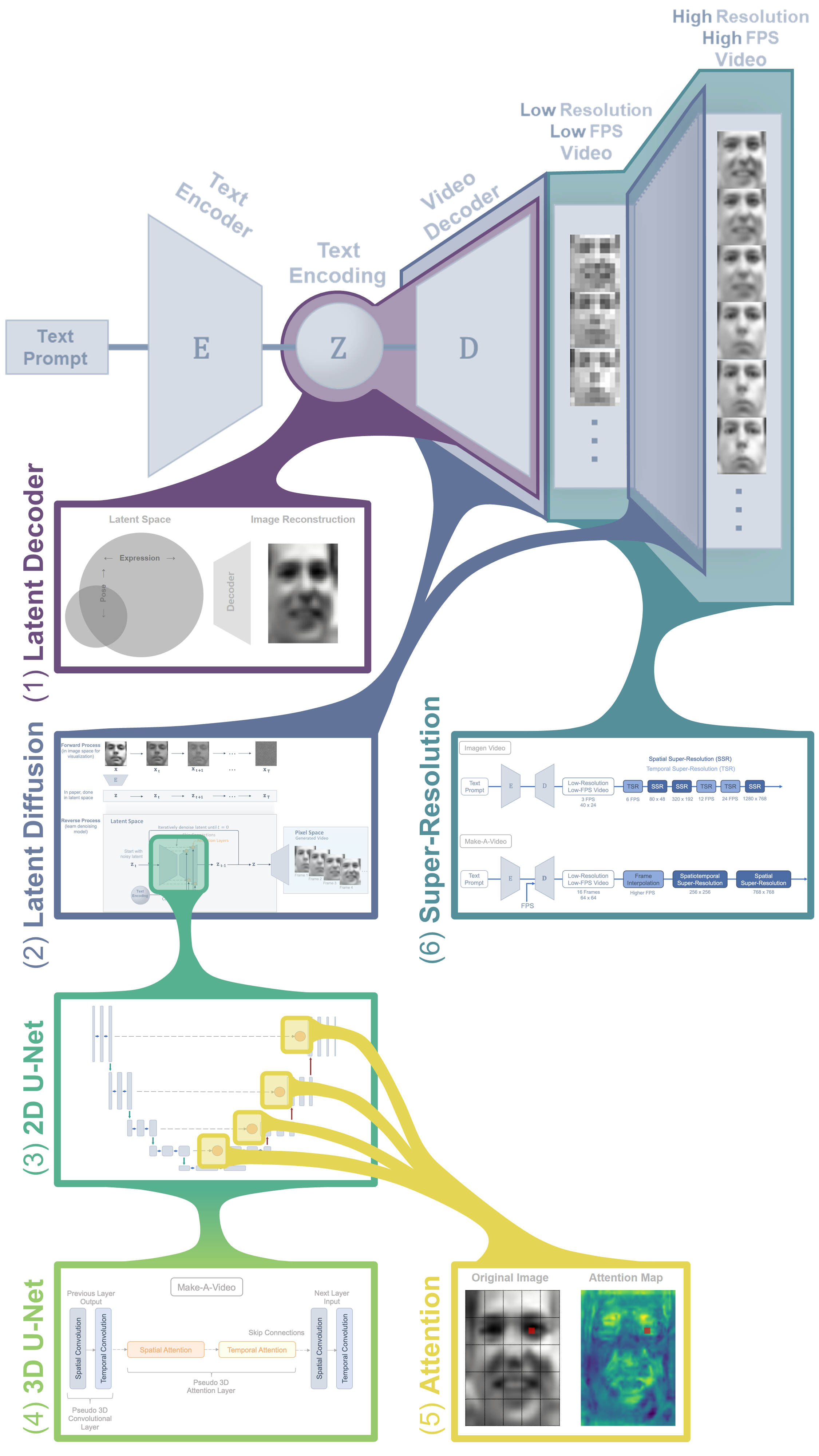

Putting Together All The Building Blocks

In this post, we have described the foundational building blocks of Text-to-Video generation of two popular models, Google’s Imagen Video and Meta’s Make-a-Video. Although these two methods have various differences, they build off of similar theory and similar building blocks. In Figure 9, we visually demonstrate how each of the consituent building blocks discussed in this post fit together to construct the larger Text-to-Video model.

The foundational building blocks of Figure 9 and their utility in Text-to-Video generation are summarized:

- Latent Decoder: An autoencoder encoding-decoding network demonstrates how data can be compressed into a low-dimensional latent representation and then by selecting different points in this latent space, new outputs are generated.

- Latent Diffusion: Training an encoding-decoding network with the stable diffusion process allows completely new images to be generated from latents with added noise. In a Text-to-Video model, image “batches” are generated from a single noisy latent put through the trained decoder to create a new, unseen video at low FPS and low resolution.

- 2D U-Net: To retain import information during the latent space compression encoding-decoding process, skip connections are added to tether the encoder with the decoder. This is a data-efficient architecture called a U-Net that is used in the encoding-decoding process of Text-to-Image.

- 3D U-Net: The 3D U-Net is an extension of the Text-to-Image 2D U-Net for Text-to-Video generation. Since it is computationally expensive to expand 2D convolution and attention directly into 3D, hence, psuedo 3D convolution and attention are constructed by concatenating 2D spatial and 1D temporal layers.

- Attention: Attention layers help determine which spatial and temporal features to pay attention to, according to the input text conditioning. In a Text-to-Video model, attention helps create realistic videos by connecting important features in each frame and across frames with less required information transfer than a standard fully-connected layer.

- Super-Resolution: Upsampling in both the spatial and temporal dimensions increases the video resolution and frame rate, respectively. In Text-to-Video, upsampling is done across image batches simultaneously or with other considerations to ensure temporal consistency.

By combining these six building blocks together, a complete Text-to-Video generation model can be constructed. Google and Meta demonstrate technically unique yet methodically similar approaches for expanding 2D Text-to-Image generation into the 3D realm while significantly improving the resolution, framerate, and temporal coherency of videos generated from text-based prompts.

Limitations of Text-to-Video

As beautiful as many of these videos are . . .

Not all of them are perfect . . . (pay close attention to the legs of the elephant walking)

Although Imagen Video and Make-a-Video have made significant progress in temporal coherency to remove flickering effects, complex videos generated where image data is sparse, have poor realism across the temporal dimension. In the elephant walking underwater example, a lack of training data of elephants walking or perhaps training sets with insufficient frame rates results in latent diffusion having to work harder to interpolate the missing frames, resulting in poor temporal realism. However, as both datasets and models continue to grow in size, the videos generated by the methods discussed in this post will improve in realism and these failure modes will become less common.

Furthermore, both models are optimized for producing shorter (5-second) videos. Since Make-A-Video directly builds on Text-to-Image, it cannot learn associations that can only be learned from videos. Longer videos containing multiple scenes and actions are challenging to generate with both of these models.

Undoubtedly, these Text-to-Video generation methods can substantially expand the creative toolbox available to artists and creators, however, key issues should be addressed before these networks become publicly available. For example, misuse of the models can result in fake, explicit, hateful, or otherwise generally harmful content. To help address this, additional classifiers can be trained to filter text inputs and video outputs. Moreover, the outputs reflect the composition of the training dataset, which include some problematic data, social biases, and stereotypes.

Related Works

Several advancements have been achieved with the methods described in this post, however, video generation is not a new concept, nor do the methods described in this post solve all video generation challenges. So, here is a selection of some other interesting video generation variations/applications developed by other researchers:

- Phenaki is another video generation tool that can generate videos of several minutes in length from story-like text prompts, compared to 5 second videos generated by Imagen Video and Make-a-Video.

- Lee et al. and Narashimhan et al. generated video synced with audio inputs.

- Visual Foresight predicts how an object will move given an action in pixel space for more practical robotics planning and control applications.

References

[1] Ramesh, A. et al. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation, 2021. arXiv Preprint.