Understanding Methods for Scalable MCTS

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is a versatile algorithm widely used for intelligent decision-making in complex, high-dimensional environments. While MCTS inherently improves with more compute, real-world applications often demand rapid decision-making under strict inference-time constraints. This blog post explores scalable parallelization strategies for MCTS, covering classical methods (leaf, root, and tree parallelism) and advanced distributed approaches—including virtual loss, transposition-driven scheduling, and distributed depth-first scheduling. By examining the practical trade-offs and performance implications of each method, we identify effective techniques for achieving high-throughput, low-latency planning—critical for applications like autonomous vehicles, emergency response systems, and real-time trading.

Intro

Recently, there has been a significant focus on training large language models (LLMs) with billions or even trillions of parameters, using vast amounts of compute for training. However, expecting these models to produce perfect answers instantaneously—especially for complex queries—is unrealistic. Consequently, the AI industry is shifting its focus toward optimizing inference-time compute, seeking ways to harness computational resources more effectively. One promising approach is to leverage scalable search algorithms that enable models to plan, reason, and refine outputs more effectively.

Rich Sutton’s bitter lesson highlights why scalability is key:

“One thing that should be learned from the bitter lesson is the great power of general-purpose methods, of methods that continue to scale with increased computation even as the available computation becomes very great. The two methods that seem to scale arbitrarily in this way are search and learning.”

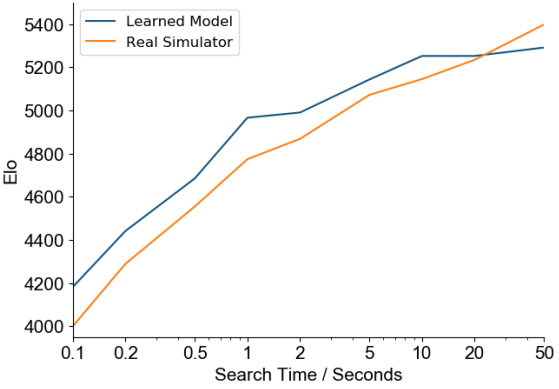

One method that exemplifies Sutton’s principle—continuing to scale effectively with more computation—is Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), demonstrating remarkable results with increased computation. This is evident in the performance of DeepMind’s MuZero in the game of Go, where MCTS-based planning achieves significant improvements as the amount of search time grows:

MuZero’s success reveals a characteristic relationship between search time and performance for the MCTS algorithm: performance typically improves logarithmically, where each doubling of computational resources adds a relatively constant increment to playing strength

In this post, we’ll explore various parallelization strategies—from leaf, root, and tree parallelism to advanced methods such as virtual loss, transposition-driven scheduling, and distributed depth-first scheduling. Our goal is to understand the practical trade-offs involved, evaluating how effectively these parallelization strategies scale MCTS in real-world scenarios.

MCTS Background

We’ll focus on MCTS with the Upper Confidence bounds applied to Trees (UCT) algorithm, which is a widely used variant that effectively balances exploration and exploitation. For simplicity, we will refer to this variant as “MCTS” throughout the post. MCTS, a powerful algorithm for decision making in large state spaces, is commonly used in games, optimization problems, and real-world domains such as protein folding and molecular design. It stands out for its ability to search complex spaces without the need for additional heuristic knowledge, making it adaptable across a variety of problems. Before MCTS became prominent, techniques like minimax with alpha-beta pruning were the standard in game AI. While alpha-beta pruning could efficiently reduce the search space, its effectiveness often depended on the quality of evaluation functions and move ordering. MCTS offered a different approach that could work without domain-specific knowledge, though both methods can benefit from incorporating heuristics

The Four Phases of MCTS

MCTS operates in an environment that defines states, actions, a transition function, and a reward function. In the diagrams below, we assume a simplified environment where both states and actions are represented as single nodes due to the environment’s deterministic transition function, and only terminal nodes yield rewards (either 0 or 1). While the diagrams represent both states and actions as single nodes for visual clarity, in MCTS it is generally the state-action pairs that collect key decision-making statistics such as average reward $Q(s, a)$ and visit counts $N(s, a)$, which are crucial inputs to the UCT formula that guides the selection process. States themselves also track visit counts $N(s)$, which influence exploration decisions.

The core of MCTS lies in its iterative tree-building process, which unfolds through a repeated cycle of four distinct phases. In the diagrams that follow, note that the values shown in the nodes represent the average rewards $Q(s, a)$ accumulated through multiple iterations. Let’s now take a closer look at how these four phases work together to guide the overall search process:

1. Selection

Starting from the root, the algorithm traverses child nodes using a policy that balances exploration and exploitation until it reaches a node with unexplored children (allowing for expansion) or a terminal node.

2. Expansion

If the selected node is not terminal, the algorithm chooses an unexplored child node randomly and adds it to the tree.

3. Simulation

From the newly expanded node, a simulation (or 'rollout') is performed by sampling actions using a default (often random) policy until a terminal state is reached. The cumulative reward obtained during this phase serves as feedback for evaluating the node.

4. Backpropagation

Once a terminal state is reached, the simulation's result is propagated back up the tree. At each node along the path, visit counts are incremented, and average rewards are updated to reflect the outcome.

MCTS is an anytime algorithm, meaning it can be stopped at any point during its execution and still return the best decision found up to that point. This is particularly useful when dealing with problems where the state space is too large to be fully explored. In practical applications, MCTS operates within a computational budget, which could be defined by a fixed number of iterations or a set amount of time.

At the conclusion of the search process, the algorithm recommends the action $a_{final}$ that maximizes the average reward $Q(s_0, a)$ among all possible actions $a$ from the root state $s_0$:

\[a_{final} = \underset{a \in A(s_0)}{\operatorname{argmax}} Q(s_0, a) \tag{1}\]where:

- $A(s_0)$ represents the set of actions available in the root state $s_0$.

- $Q(s_0, a)$ represents the average reward from playing action $a$ in state $s_0$ based on simulations performed so far.

As the number of iterations grows to infinity, the average reward estimates $Q(s_0, a)$ for each of the actions from the root state converge in probability to their minimax optimal values

The UCT Selection Policy

A key component of MCTS is the Upper Confidence Bounds for Trees (UCT) algorithm, introduced by Kocsis and Szepesvári

During the selection phase, the algorithm chooses actions based on the statistics of actions that have already been explored within the search tree. The action $a_{selection}$ to play in a given state $s$ is selected by maximizing the UCT score shown in brackets below:

\[a_{selection} = \underset{a \in A(s)}{\operatorname{argmax}} \left\{ \underbrace{Q(s, a)}_{\text{exploitation term}} + \underbrace{C \sqrt{\frac{\ln N(s)}{N(s, a)}}}_{\text{exploration term}} \right\} \tag{2}\]where:

- $a_{selection}$ is the action selected from state $s$.

- $A(s)$ is the set of actions available in state $s$.

- $Q(s, a)$ represents the average reward from playing action $a$ in state $s$ from simulations performed so far.

- $N(s)$ is the number of times state $s$ has been visited.

- $N(s, a)$ is the number of times action $a$ has been played from state $s$.

- $C$ is a constant controlling the balance between exploration and exploitation. In general, it is set differently depending on the domain.

In the formula, the exploitation term favors actions that have yielded high rewards in past simulations, encouraging the algorithm to revisit promising search paths. The exploration term, in contrast, gives a bonus to actions that have been selected less frequently, pushing the algorithm to try out underexplored branches of the tree.

This concludes our discussion of the foundational elements of MCTS, providing the necessary context for understanding scalable adaptations of the algorithm. For a deeper dive into MCTS, I highly recommend this guide by Tim Miller.

How can we scale MCTS?

While MCTS naturally improves solution quality with additional computation time, one of its most compelling advantages is its ability to leverage parallel compute to find better solutions within a fixed time budget. This capability is critical for real-world applications where decisions must be made under strict time constraints. By distributing computation across multiple processors, parallel MCTS implementations can deliver dramatically better solutions without extending wall-clock time—a fundamental advantage in time-sensitive domains.

The importance of this parallelization becomes clear when addressing high-stakes scenarios such as autonomous vehicle navigation, emergency response planning, or real-time financial trading, where improving decision quality without sacrificing response time is critical. However, parallelizing MCTS without degrading its performance is non-trivial, as each iteration depends on information accumulated in previous iterations to maintain an effective exploration-exploitation tradeoff

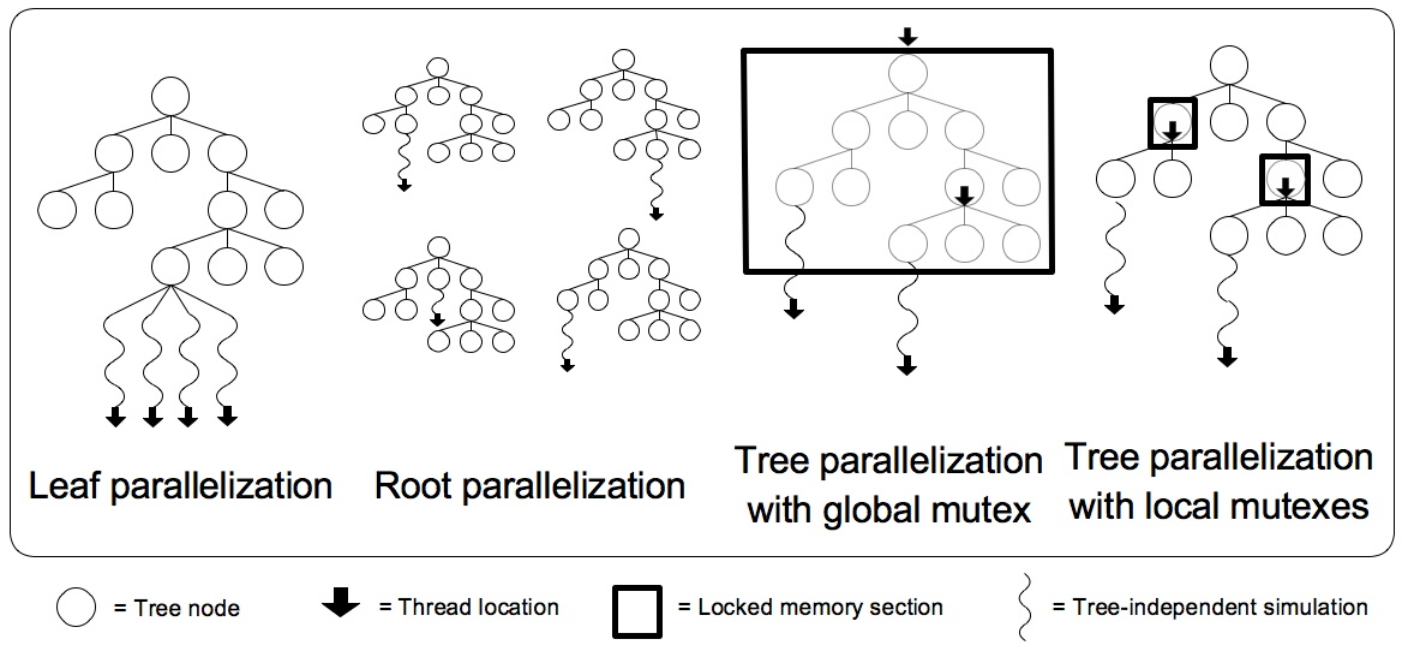

To tackle the challenges of parallel MCTS, researchers have introduced three primary strategies—leaf, root, and tree parallelism—each with different tradeoffs in coordination and efficiency. The figure below provides a visual overview of these approaches, which we’ll explore in the sections that follow.

Leaf Parallelism

Leaf parallelism focuses on the simulation phase of MCTS. Once a new leaf node is expanded, simulations from that node can be distributed across multiple workers. This enables a high degree of parallelism with minimal coordination overhead, as each worker can perform rollouts independently. The results are then aggregated to update the value estimate for the expanded node. By increasing the number of rollouts performed in the same amount of wall-clock time, leaf parallelism helps reduce the variance of value estimates, leading to more stable evaluations of action quality.

However, the effectiveness of this approach depends heavily on the quality of the rollouts. If early simulations suggest an action has low value, continuing to allocate resources to that action may be a poor use of compute. Additionally, leaf parallelism only accelerates a single phase of MCTS and doesn’t improve the overall tree-building process. Chaslot et al. found that the benefits of this method are relatively limited and concluded that it is not an effective strategy for scaling MCTS in practice

Root Parallelism

Root parallelism distributes the entire MCTS process across multiple worker machines, with each worker building an independent search tree from the same root state. This approach is conceptually simple and avoids the complexity of coordinating shared memory or synchronizing updates. It resembles ensemble methods in machine learning, where multiple models independently evaluate a problem and their outputs are aggregated to form a final decision.

Since each tree explores the search space independently, root parallelism promotes diversity in the trajectories explored, increasing the likelihood of discovering high-quality actions that might be missed by a single search. However, it also leads to redundant computations across workers, as each tree may revisit similar states without benefiting from the insights gathered by others

At the end of the time budget, results from all trees are aggregated—typically by majority vote or averaging the action-value estimates—to select the most promising action. While root parallelism is easy to implement and requires minimal communication, its lack of information sharing often leads to inefficiencies, limiting its effectiveness compared to more coordinated approaches.

Tree Parallelism

Tree parallelism, which will be the focus for the remainder of this blogpost, is widely used in modern distributed MCTS implementations and is the method of choice in the AlphaGo line of work

There are many compelling reasons to use tree parallelism:

- It often yields higher-quality solutions within a fixed wall-clock time.

- It explores more of the game tree, increasing the likelihood of discovering the optimal trajectory (sequence of actions).

- It fully utilizes accelerators (GPUs, TPUs, etc.).

Yet at the same time, there are many challenges:

- MCTS relies on the statistics gathered from previous iterations to guide future decisions. In tree-parallel implementations, these statistics may become outdated due to concurrent updates, potentially leading to suboptimal traversal of the search tree.

- Evaluating actions far from the optimal trajectory can degrade performance, as rollout variability and approximation errors may cause suboptimal actions to appear overly promising

. - Managing concurrent access to the tree and ensuring data integrity introduces complexity. For instance, race conditions or data overwrites could corrupt the search process

.

To fully leverage tree parallelism while maintaining decision quality, researchers have developed a range of strategies to address its key challenges: avoiding redundant work, coordinating concurrent updates, and maintaining consistency in shared memory. In the sections that follow, we’ll explore how techniques like virtual loss, synchronization mechanisms (both lock-based and lock-free), and distributed scheduling (e.g., TDS) tackle these issues and enable scalable, high-performance MCTS implementations.

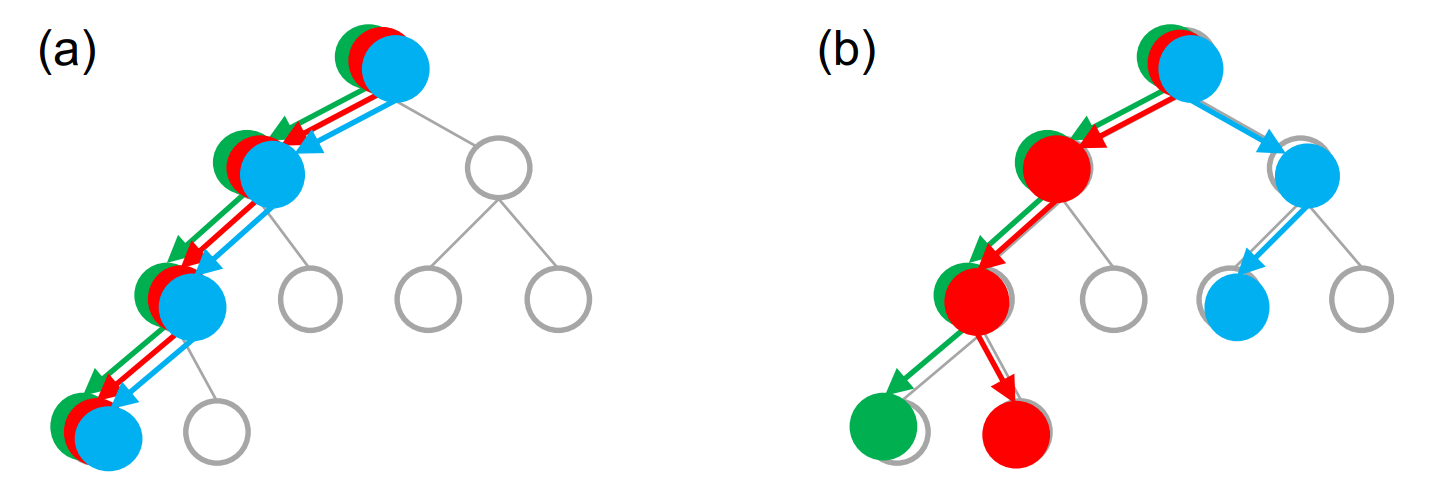

Virtual Loss

A key challenge in parallelizing MCTS is that multiple workers may select the same path through the tree during the selection phase, leading to redundant exploration and wasted compute. A common technique for addressing this issue is virtual loss, which temporarily penalizes nodes being explored to encourage diversity among worker trajectories. The idea is to adjust UCT scores dynamically: when a node is selected by one worker, it is treated as temporarily less favorable for others. This is typically achieved by assuming the node will return a reward of zero until the rollout is complete and the result is backpropagated.

To illustrate how virtual loss increases trajectory diversity, consider the following diagram from Yang et al., which compares parallelization with and without virtual loss. In this scenario, we assume that there are multiple workers traversing the search tree at the same time, but they perform selection in some specific order. As a result, virtual loss reduces UCT scores for nodes being explored, enabling subsequent workers to take distinct search paths and avoid redundant computation.

To implement virtual loss, the UCT selection policy is modified to account for ongoing rollouts. The adjusted formula is:

\[a_{selection} = \underset{a \in A(s)}{\operatorname{argmax}} \left\{ \frac{N(s, a)Q(s, a)}{N(s, a) + T(s, a)} + C \sqrt{\frac{\ln (N(s) + T(s))}{N(s, a) + T(s, a)}} \right\} \tag{3}\]In this formula, two additional terms—$T(s, a)$ and $T(s)$—are introduced to account for ongoing parallel rollouts.

- $T(s, a)$ is the number of ongoing searches through action $a$ in state $s$.

- $T(s)$ is the number of ongoing searches through state $s$, defined as $\sum_{a \in A(s)} T(s, a)$

The exploitation term (first term) is modified by assuming that rollouts currently in progress contribute zero reward, which lowers the average value estimate for that action. This discourages multiple workers from selecting the same action simultaneously. Meanwhile, the exploration bonus (second term) is adjusted to reflect the presence of ongoing searches, encouraging selection of actions that are both underexplored and not currently being evaluated.

While virtual loss encourages exploration, its fixed assumption of zero reward for in-progress rollouts can overly penalize promising nodes, limiting exploitation

Just as in virtual loss, $T(s, a)$ penalizes nodes that are part of many ongoing searches. However, instead of assuming a reward of zero, WU-UCT assumes the reward will be $Q(s, a)$—the average observed so far. By penalizing only the exploration term, WU-UCT aims to balance trajectory diversity with more accurate value estimation.

Liu et al. found that their WU-UCT approach achieved near-linear speedups as the number of workers increased, with only minor performance degradation compared to sequential MCTS across a benchmark suite of 15 Atari games

Lock-Based and Lock-Free Tree Parallelism

One of the main challenges in tree parallelism is managing resource contention when multiple threads attempt to read or write to the shared tree simultaneously. To address this, the literature proposes two primary synchronization strategies: lock-based and lock-free methods.

Global mutex methods use a single lock to control access to the entire tree during critical operations such as selection, expansion, and backpropagation. Simulations—which don’t modify the tree—can proceed without acquiring the lock. This approach is simple to implement but introduces a major bottleneck: only one thread can modify the tree at a time, causing others to wait. As a result, global mutex methods offer poor scalability and are only practical for systems with a small number of threads.

Local mutex methods offer a finer-grained alternative by locking only the node currently being accessed. This allows multiple threads to operate on different parts of the tree in parallel, dramatically improving throughput. However, it also introduces additional overhead due to the need to manage many locks. Chaslot et al. recommend using fast-access synchronization primitives such as spinlocks, which are well-suited for situations where locks are held for very short durations

Because lock-based methods can incur coordination overhead and implementation complexity, some systems opt for lock-free approaches, which use atomic operations and memory consistency models to enable safe concurrent access without explicit locking

Distributed MCTS - WU-UCT

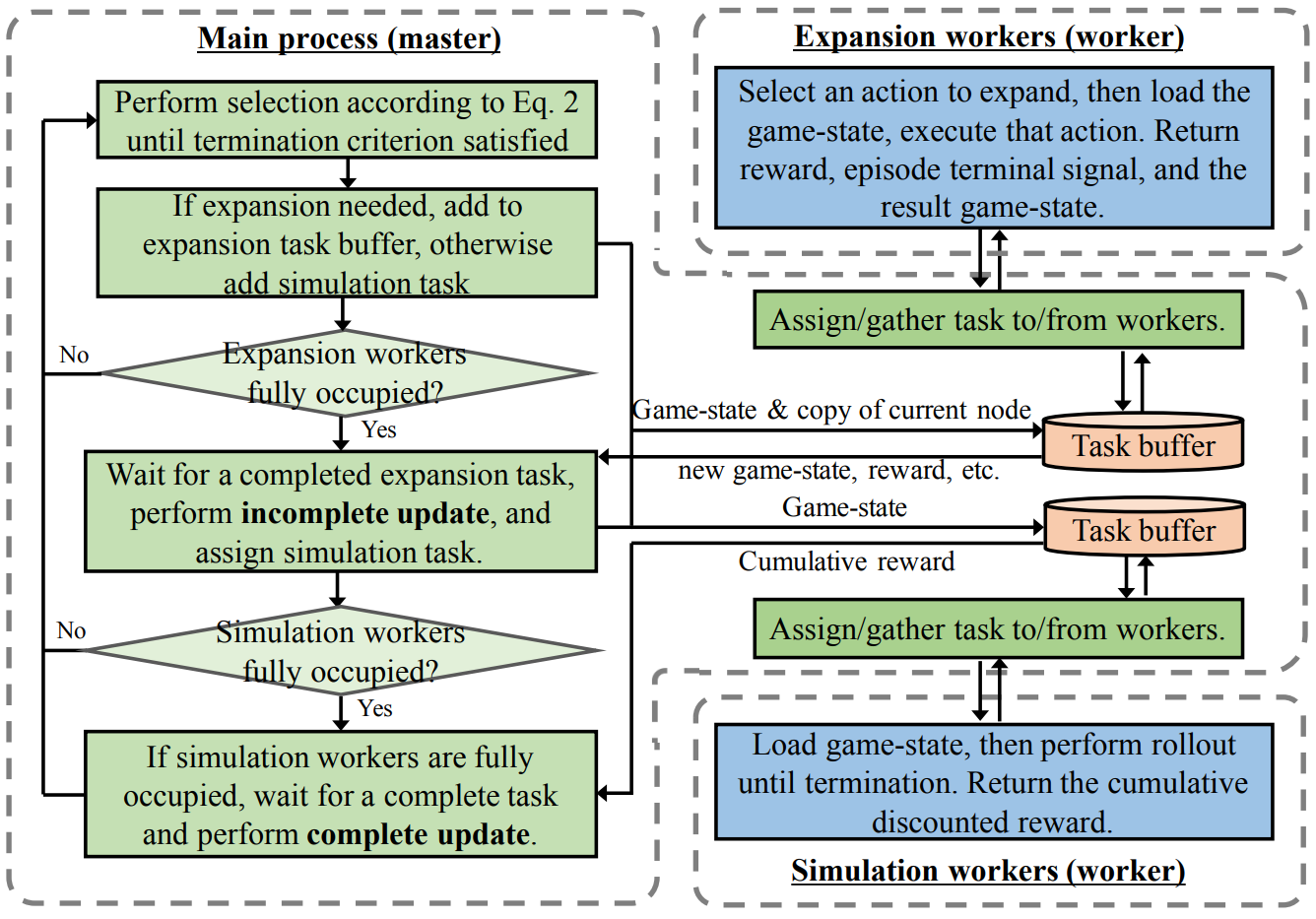

To scale MCTS to large state spaces, Liu et al. proposed a distributed framework that decouples the algorithm’s core phases into separate tasks. These tasks are executed in parallel across specialized roles: a master process, expansion workers, and simulation workers.

- Master Process: Coordinates the overall search and maintains the shared data structures, including the search tree and node statistics. It performs selection, manages task queues, and delegates expansion and simulation tasks to workers.

- Expansion Workers: Perform both selection and expansion by traversing the search tree with the UCT policy until an unexplored leaf node is reached. They then execute the selected action in the environment and return the resulting state, reward, and terminal signal to the master. Upon receiving this result, the master applies an incomplete update, adjusting statistics using the virtual loss formulation from WU-UCT.

- Simulation Workers: Perform rollouts from the states returned by expansion workers, simulating trajectories until termination. They return the cumulative discounted reward to the master, which then applies a full backpropagation update.

The diagram below from Liu et al. illustrates how the master process coordinates task assignment, worker communication, and updates during the distributed MCTS procedure.

By decoupling expansion from simulation, the framework parallelizes MCTS without interfering with the integrity of the search. The master tracks ongoing searches and ensures that updates to shared node statistics remain consistent.

Although this framework requires frequent communication between the master and workers, Liu et al. found that the computation time of expansion and simulation far outweighs the messaging overhead. As a result, the system scales effectively across many machines without communication becoming a bottleneck.

Distributed MCTS - TDS

In 2011, Yoshizoe et al.

TDS assigns each node in the search tree to a specific “home” worker using a hash function. This guarantees an even data distribution and allows each worker to store and manage only its assigned subset of the tree. Rather than transferring data across machines, workers forward requests to the appropriate owner, who processes them locally and returns the result. This design is very efficient, as moving data across a network is generally far slower than encoding requests to process that data and sending the requests where the data resides.

TDS communication is fully asynchronous: when a worker issues a request, it does not wait for the response before continuing its own computation. The target worker processes the request in parallel and returns the result when ready. This overlap between computation and communication maximizes throughput and avoids idle time.

Yoshizoe et al.

This architecture stands in sharp contrast to the WU-UCT framework. While WU-UCT distributes the phases of MCTS across workers—assigning selection, expansion, and simulation to different processes—it maintains a centralized tree, with all workers sharing access to global node statistics. In contrast, TDS distributes the tree itself, assigning each node to a specific worker via hashing, while allowing each worker to execute all phases of MCTS locally on its assigned nodes. This design difference leads to distinct trade-offs in communication patterns, load balancing, and update latency.

Despite its efficiency, TDS introduces several tradeoffs. Asynchronous communication can lead to stale reads, where workers operate on outdated node statistics. Moreover, nodes near the root receive a disproportionate number of requests, creating load imbalances that can bottleneck the entire system. These limitations must be managed carefully to preserve scalability.

Distributed Depth-First MCTS

To address workload imbalance in distributed MCTS, Yoshizoe et al.

Like TDS, TDS-df-UCT assigns nodes to workers using a hash-based partitioning scheme, enabling asynchronous computation and minimizing data movement. However, delaying backpropagation introduces several tradeoffs:

- Shallow Trees: With fewer backpropagations, important discoveries may not propagate in time, causing the tree to expand horizontally rather than deeply—unlike traditional MCTS, which updates statistics more frequently.

- Delayed Information Sharing: Since history is carried only in messages exchanged between workers, knowledge of promising trajectories spreads more slowly, limiting coordination.

Even with these limitations, TDS-df-UCT delivers substantial speedups by leveraging distributed resources and reducing communication overhead.

To address the shortcomings of TDS-df-UCT, Yang et al. introduced Massively Parallel MCTS (MP-MCTS)—a refined algorithm designed for large-scale search tasks such as molecular design. MP-MCTS introduces several innovations to improve information sharing and search depth

- Node-Level History Tables: Unlike TDS-df-UCT, where history is carried only in messages, MP-MCTS stores detailed statistical histories (e.g., visit counts and rewards) within each node. This accelerates the dissemination of the latest simulation results across workers and allows for more informed decisions during traversal.

- Strategic Backpropagation: MP-MCTS introduces a more dynamic backpropagation strategy, where updates are performed as needed to maintain accurate UCT value estimates. This prevents over-exploration of less promising branches while ensuring timely propagation of critical information.

- Focused Exploration: By enabling workers to leverage the most up-to-date statistics, MP-MCTS directs rollouts toward deeper, more promising parts of the tree, resulting in higher-quality solutions.

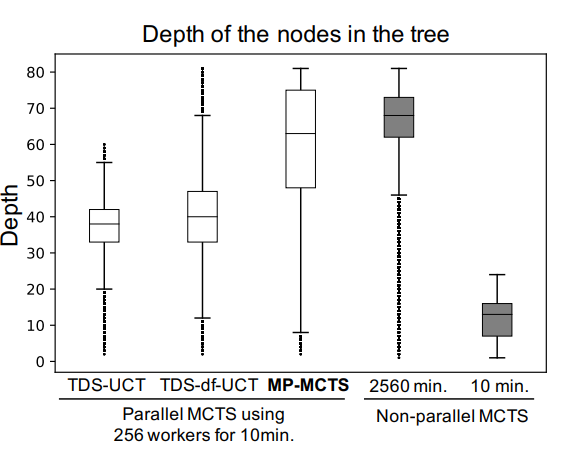

These enhancements enable MP-MCTS to approximate the behavior of sequential MCTS while achieving substantial speedups in distributed environments. The figure below demonstrates how MP-MCTS consistently produces deeper trees compared to TDS-df-UCT and even approaches the search depth achieved by non-parallel MCTS with equivalent computational resources:

Experiments show that MP-MCTS not only achieves deeper trees but also consistently outperforms TDS-df-UCT in solution quality. In molecular design benchmarks, MP-MCTS running on 256 cores for 10 minutes found solutions comparable to non-parallel MCTS running for 2560 minutes

Distributed depth-first MCTS approaches like TDS-df-UCT and MP-MCTS represent a significant step forward in scaling MCTS for large-scale distributed environments. While TDS-df-UCT introduced foundational ideas for mitigating communication bottlenecks, MP-MCTS refined these concepts to achieve better tree depth, scalability, and solution quality. By cleverly reducing backpropagation overhead and introducing node-level history tables, these methods achieve significant speedups while approximating the behavior of sequential MCTS.

Conclusion

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) remains one of the most powerful tools for intelligent decision-making, powering systems like MuZero and demonstrating flexibility across domains. While inherently sequential, MCTS can be scaled effectively through parallel and distributed strategies that preserve its core exploration-exploitation behavior. Techniques such as leaf, root, and tree parallelism—along with innovations like virtual loss and transposition-driven scheduling—make it possible to scale to deeper search trees and discover better solutions under tight time constraints.

No single parallel MCTS method is optimal in all contexts, as each involves inherent trade-offs between communication costs, compute efficiency, and information sharing. The choice of parallelization strategy must therefore align closely with the system’s architecture and practical constraints. This becomes particularly critical in time-sensitive domains—such as autonomous vehicle navigation, emergency planning, or high-frequency trading—where decisions are required within milliseconds. In these scenarios, the ability to effectively distribute computation to enhance decision quality without increasing latency is vital.

As inference-time compute becomes increasingly important, scalable planning algorithms like MCTS will play a central role in bridging learning and reasoning. Understanding when and how to apply different parallelization strategies is key to unlocking their full potential.