Repurposing in AI: A Distinct Approach or an Extension of Creative Problem Solving?

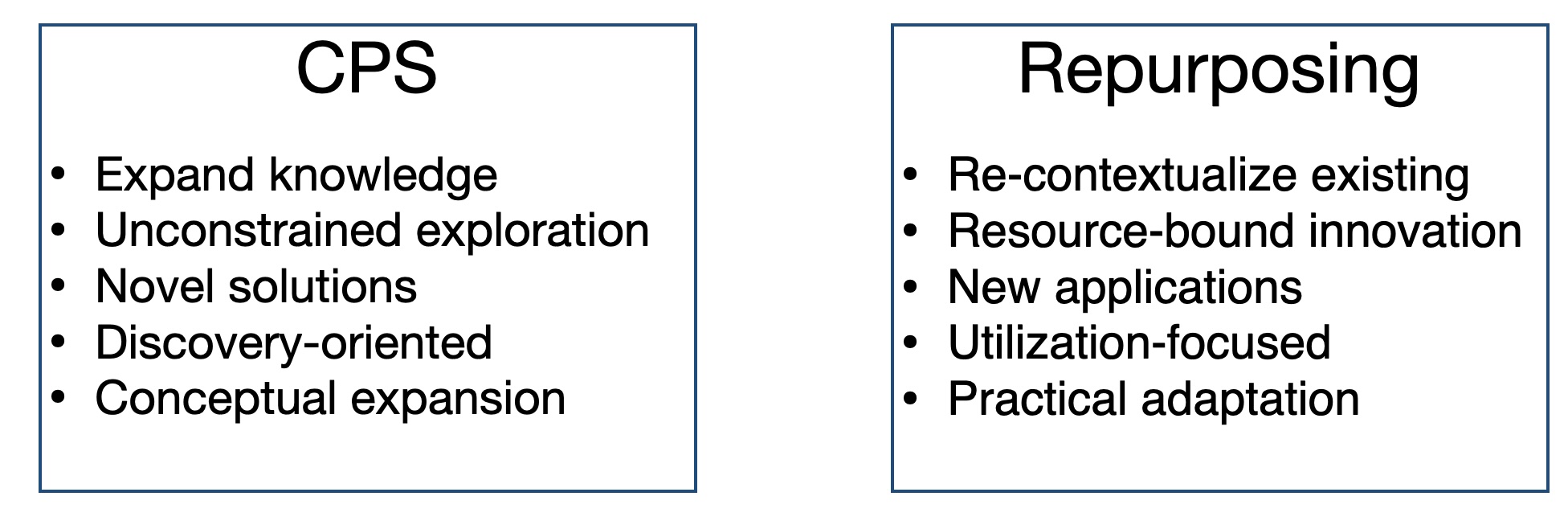

Creativity is defined as the ability to produce novel, useful, and surprising ideas. A sub area of creativity is creative problem solving, the capacity of an agent to discover novel and previously unseen ways to accomplish a task, according to its perspective. However, there is a related concept, repurposing, that has often been overlooked in the broader context of creative problem solving in AI. Repurposing involves identifying and utilizing existing objects, resources, or processes in innovative ways to address different problems. While these two concepts may seem distinct at first glance, recent studies in creativity in AI suggest that they may be more closely intertwined than previously thought. By examining the underlying mechanisms and cognitive processes involved in both creative problem solving and repurposing, we can begin to understand how these approaches complement each other.

In an era of rapid technological advancement and resource constraints, repurposing has emerged as a crucial strategy for sustainable innovation and efficient problem-solving. The ability to adapt existing solutions to new challenges promotes efficiency. Repurposing allows us to maximize the utility of our resources, reduce waste, and find novel solutions to complex problems while adapting existing solutions to new challenges. There are several use cases, from transforming industrial waste into valuable products to repurposing drugs for new medical treatments.

This blog post aims at exploring the boundaries of creative problem solving (CPS) and proposes repurposing as a valid solution for those limitations. The section on CPS is based on

Creative Problem Solving

Creative Problem Solving is defined as the cognitive process of searching and coming up with creative and novel solutions to a given problem

Definition of Creative Problem Solving

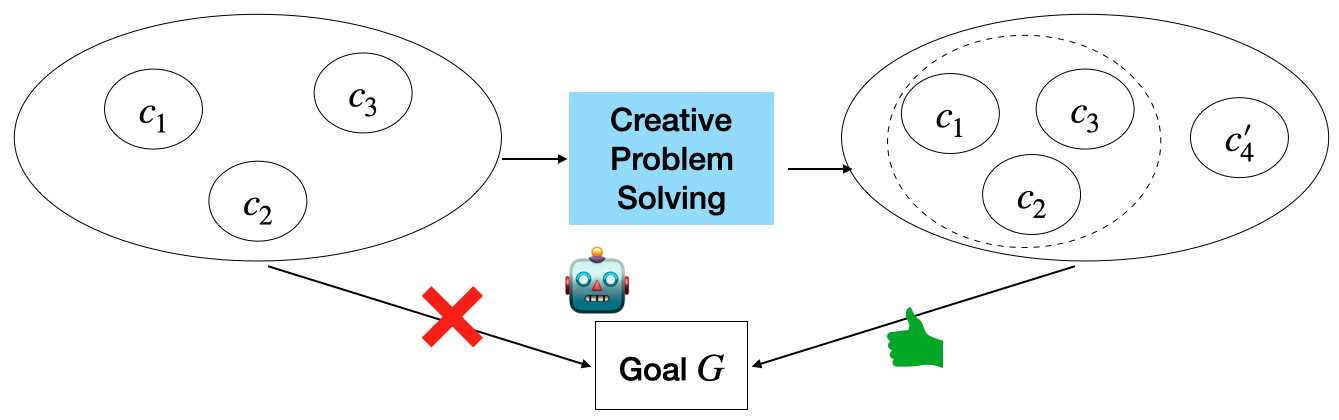

We borrow and adapt the mathematical formalization from the creative problem solving framework proposed by

In this framework, concepts, are defined as either states of the environment and/or agent or actions. \(C_X\) it the set of all concepts relating to \(X\), with \(X\) being environment states \(S\) or actions \(A\). In the creative problem solving framework, a goal \(G\) is un-achievable if the conceptual space \(C_X\) is unsufficient. To achieve the goal \(G\), the agent needs to discover a new conceptual space \(C_X' \not\subset C_X\) such that \(C_X' = f(C_X)\). Creative problem solving is the process of finidng \(f\) to apply to the current conceptual space \(C_X\) to find \(C'_X\).

This raises an important question: what is a conceptual space?

A “[conceptual space] is the generative system that underlies the domain and defines a certain range of possibilities: chess moves, or molecular structures, or jazz melodies. … in short, any reasonably disciplined way of thinking”.

Loosely speaking, the conceptual space of an agent is essentially its embedding space, that is to say, the space where the agent organizes data points to to efficiently encode real-world data and relationships.

While this example effectively demonstrates creative problem solving through conceptual expansion, it illustrates a potentially inefficient approach to the problem. The agent must undergo a process of discovery and knowledge expansion when a more direct solution might be available. The same scenario can be analyzed through the lens of repurposing, which offers a more resource-efficient perspective focused on leveraging existing knowledge rather than expanding it. To fully understand this alternative approach, we need to introduce the critical concepts of resources and adaptability that form the foundation of the repurposing framework. These concepts will help illustrate how the same problem can be solved without requiring conceptual expansion, potentially offering a more computationally efficient solution path.

Repurposing

Repurposing is the process of adapting or transforming an existing concept, object, or solution to serve a new purpose or solve a different problem. At its core, repurposing is about seeing beyond the original intent and recognizing latent potential. It involves creative thinking to identify potential new uses for established ideas or resources but the creative component is not always necessary.

Unlike creative problem-solving, which discovers new concepts, repurposing focuses on finding new ways to use existing resources within the current conceptual space. This process incorporates various aspects of creativity under the form of exploration of existing features of concepts.

Repurposing transcends simple reuse by requiring a methodical analysis of resource properties and their potential applications in novel contexts. While creative problem-solving expands the conceptual space through discovery functions, repurposing works within existing boundaries by identifying how known resources can fulfill different roles based on their inherent properties. The ultimate objective is maximizing efficiency by leveraging existing resources and knowledge rather than expanding our understanding into new territories.

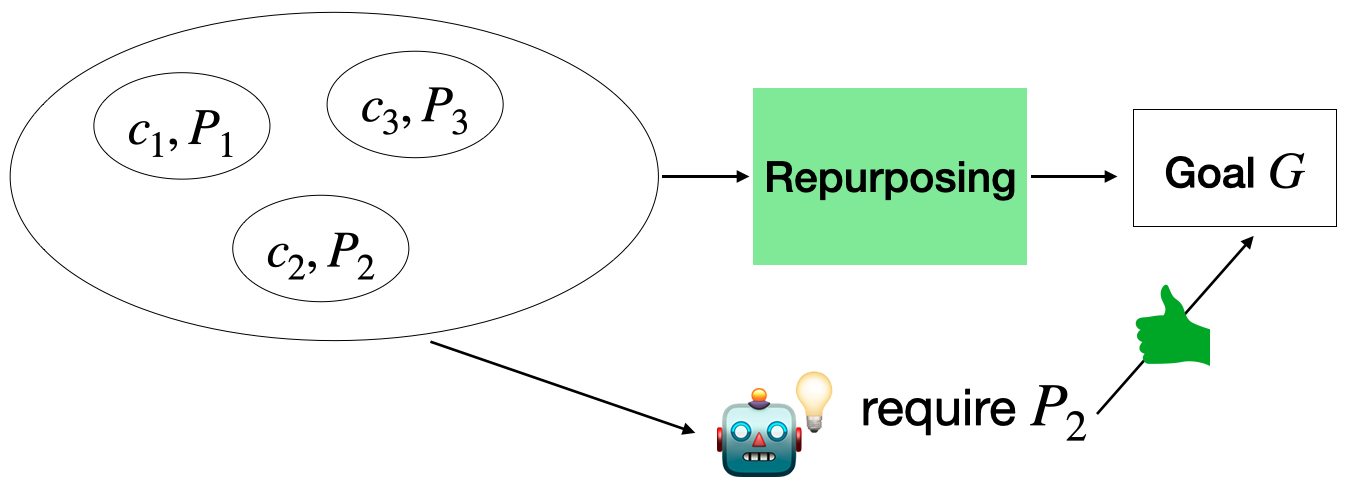

Definition of Repurposing

Contrary to creative problem solving, repurposing does not involve expanding the conceptual space, but rather involves finding new ways to use or interpret existing concepts within the current conceptual space \(C_X\) to achieve the goal \(G\). In other words, repurposing works within an existing conceptual space but changes the mapping between concepts based on their properties.

Let \(P\) be the set of all properties, and \(p: R → P\) be a property mapping function that identifies the properties of resources. Repurposing can be formally defined as a process that operates within:

- An existing conceptual space \(C_X\)

- A set of available resources \(R = {r_1, r_2, ..., r_n}\)

- A property mapping function \(p\) to achieve a goal \(G\).

Unlike creative problem solving which expands the conceptual space, repurposing focuses on finding new mappings between existing resources and concepts based on their shared properties.

The success of repurposing depends on three key factors:

- The existing conceptual space C_X

- The properties of available resources identified through \(p(R)\)

- The adaptability (\(a\)) of the available resources \(R\) which quantifies how effciently the existing resources can be repurposed to meet the new goal. It’s a measure of the flexibility of our resources and the efficiency of our repurposing solution. We define the adaptability score as: \(a = 1 - \frac{n}{N}\), where:

- $n$ is the number of resources that need to be replaced or added to achieve the repurposing goal

- $N$ is the total number of resources in the original concept

- a = 1 indicates perfect repurposing (using existing resources as-is)

- a = 0 indicates complete replacement (not really repurposing)

A higher adaptability score indicates a more efficient repurposing solution, as it requires fewer modifications to existing resources. This metric provides a quantitative way to evaluate and compare different repurposing strategies, prioritizing those that maximize the utility of available resources.

Therefore, repurposing finds a function \(r\) where: \(r: (C_X, R, p) → G\) where \(r\) is a new interpretation/mapping function that achieves \(G\) using the same \(C_X\) by leveraging the properties identified by \(p\).

Let us revisit the previous example used to describe creative problem solving, now reframed through the lens of repurposing:

This approach fundamentally differs from creative problem solving, which would expand \(C_S\) to include hasContainability(glass) as newly discovered knowledge. In contrast, repurposing leverages existing knowledge about properties to identify suitable resource substitutions within the current conceptual space. The robot doesn’t “learn” that the glass has containability—it recognizes that this known property of the glass can be applied in a different context. This distinction highlights the efficiency advantage of repurposing: it doesn’t require conceptual expansion or knowledge discovery, just recognition of how existing properties can be applied in novel contexts. For resource-constrained systems or time-sensitive applications, repurposing often provides a more direct path to problem resolution than creative problem solving.

This distinction highlights the efficiency advantage of repurposing: it doesn’t require conceptual expansion or knowledge discovery, just recognition of how existing properties can be applied in novel contexts. For resource-constrained systems or time-sensitive applications, repurposing often provides a more direct path to problem resolution than creative problem solving.

Repurposing procedure

To systematically determine how resources can be effectively repurposed, we employ a structured analytical process that focuses on identifying and leveraging inherent properties rather than expanding conceptual boundaries:

- Property Mapping:

- Define a comprehensive property mapping function \(p: R \rightarrow P\) that identifies all relevant properties

- For each available resource \(r \in R\), methodically identify its complete set of properties \(p(r)\)

- Create a detailed mapping of the properties required to achieve goal \(G\)

- Resource Analysis:

- Rigorously compare the properties of available resources \(p(r)\) with those required to achieve \(G\)

- Identify resources that share critical properties with the tools needed for the task

- For example:

- \(p\)(spoon) = \(\{\)hasContainability, hasHandle, isRigid\(\}\)

- \(p\)(glass) = \(\{\)hasContainability, isTransparent, hasVolume, isRigid\(\}\)

- Note that both share the critical property “hasContainability” needed for scooping

- Compatibility Assessment:

- Evaluate which resources can serve as effective substitutes based on their shared properties

- Identify any property gaps that might impede successful repurposing

- Prioritize resources with the highest property overlap relevant to the task

- Transformation Requirements:

- Quantify resources that require modification to achieve the required properties

- Identify any additional properties that need to be introduced or enhanced

- Assess the complexity and feasibility of necessary transformations

- Adaptability Score: \(a = 1 - \frac{n}{N}\) where:

- \(N\) represents the total number of resources in the original solution

- \(n\) represents the number of resources that required property modifications or substitutions

This structured framework emphasizes a key distinction: repurposing operates by transferring known properties from one context to another, rather than discovering entirely new properties as in creative problem solving. When the glass is repurposed for scooping beans, the agent isn’t discovering that glasses have containability in general (it already knows glasses hold liquids), but rather recognizing that this property can transfer to a new context (holding beans). This contextual transfer of properties is often more computationally efficient than expanding the conceptual space to include entirely new knowledge.

By focusing on property matching rather than conceptual expansion, repurposing offers a more computationally efficient approach that maximizes the utility of available resources. This procedure provides agents with a systematic method to identify alternative applications for existing resources, potentially solving problems more efficiently than approaches requiring knowledge expansion.

Evaluating Repurposing Success

Evaluating the success of repurposing requires considering both how well the goal is achieved and how effectively existing resources are utilized. This evaluation must account for the properties of resources (through function \(p\)), the conceptual space constraints, and the specific requirements of the goal \(G\).

Solution Viability

The viability of a repurposing solution depends on how well it achieves the intended goal while utilizing existing resources and their properties. This assessment needs to consider multiple criteria, from the basic functionality to the practicality of the resource transformations. The evaluation must also account for how well the solution works within the constraints of the existing conceptual space \(C_X\).

To assess the effectiveness of repurposing, we introduce a task solvability function: \(S(G, C_X, R, p) = \frac{1}{|K|} \sum_{k \in K} w_k \cdot s_k(G, C_X, R, p)\) Where:

- \(K\) is the set of criteria that define goal satisfaction

- \(w_k\) is the weight of criterion \(k\) (with \(\sum_{k \in K} w_k = 1\))

- \(s_k(G, C_X, R, p)\) is the satisfaction score of criterion \(k\), ranging from 0 to 1

- \(p\) is the property mapping function that identifies resource capabilities

This function returns a value between 0 and 1, representing the degree to which the repurposing solution satisfies the goal criteria while working within the existing conceptual space and utilizing available resources.

Comparing Creative Problem-Solving and Repurposing

While both approaches aim to achieve the same goal, they differ fundamentally in how they utilize and transform available resources and conceptual spaces. These differences have significant implications for computational efficiency, resource utilization, and solution generation. To illustrate these distinctions clearly, let’s analyze a practical example: transforming a classic Italian pasta dish into a low-carb alternative.

Creative Problem-Solving Framework

-

Define the Conceptual Space: Let \(C\) be the space of all possible dishes, where each dimension represents specific culinary attributes such as ingredients, cooking methods, flavors, textures, nutritional properties, and cultural associations.

-

Initial Concept: \(c\) = Spaghetti Bolognese, represented as a specific point in the conceptual space \(C_X\)

-

Goal Definition: \(G\) = Create a low-carb alternative while maintaining the essential flavor profile and eating experience

-

Creative Operator Identification: The challenge is to find a transformation function \(f\) that expands the conceptual space to include previously unconsidered possibilities: \(C'_X = f(C_X)\) where \(C'_X \not\subset C_X\)

-

Transformation Application: Through conceptual expansion, the agent discovers that vegetables can be transformed into pasta-like structures, creating a new solution \(c' \in C'_X\) = Zucchini Noodle Bolognese

-

Solution Evaluation: We define an evaluation function \(E(c, G)\) that quantifies how effectively the new concept \(c'\) satisfies the goal \(G\) across multiple dimensions (carbohydrate content, taste similarity, texture, etc.). If \(E(c', G) > E(c, G)\), then the creative transformation is considered successful.

In this framework, the agent must actually expand its conceptual understanding to include the novel concept that vegetables can be transformed into noodle-like structures—a concept that wasn’t previously part of its culinary knowledge space. This represents genuine conceptual expansion rather than just reconfiguring existing knowledge.

Repurposing Framework

On the other hand, repurposing focuses on finding new uses for existing resources within the current conceptual space. Unlike creative problem-solving, it emphasizes identifying and leveraging shared properties of resources to achieve goals without expanding the conceptual space itself.

- Define the Conceptual Space and Properties: \(C_X = C_S ∪ C_A\) Where: \(C_S = \{\)pasta dish, Italian cuisine, high-carb meal\(\}\) \(C_A\) = {\(cook, prepare ingredients, serve\)}$$

Property mapping function p identifies: \(p\)(pasta) = {\(hasCarbs, hasTexture\)}\(\)p(\(vegetables) = \{\)hasVolume, hasTexture\(\}\)

-

Initial Resources: \(R = \{\)pasta, ground beef, tomatoes, herbs, cooking equipment\(\}\) with their associated properties \(p(r)\) for each \(r \in R\)

-

Goal: \(G\) = Create a low-carb alternative

- Repurposing Process: a) Identify resources with properties matching goal requirements b) Modify resource usage based on shared properties:

- Reduce pasta quantity by 2/3

- Use tomatoes’ hasVolume property to increase sauce, cooking them down to a thicker sauce

- Leverage herbs’ flavor properties for satisfaction

-

Solution Implementation: Modified resource usage: \(R' =\){reduced pasta, ground beef, increased tomatoes, increased herbs, cooking equipment}

- Evaluate Solution Viability: Calculate \(S(G, C_X, R, p)\) to assess goal satisfaction (Calculate adaptability score a = 1 - n/N post-hoc)

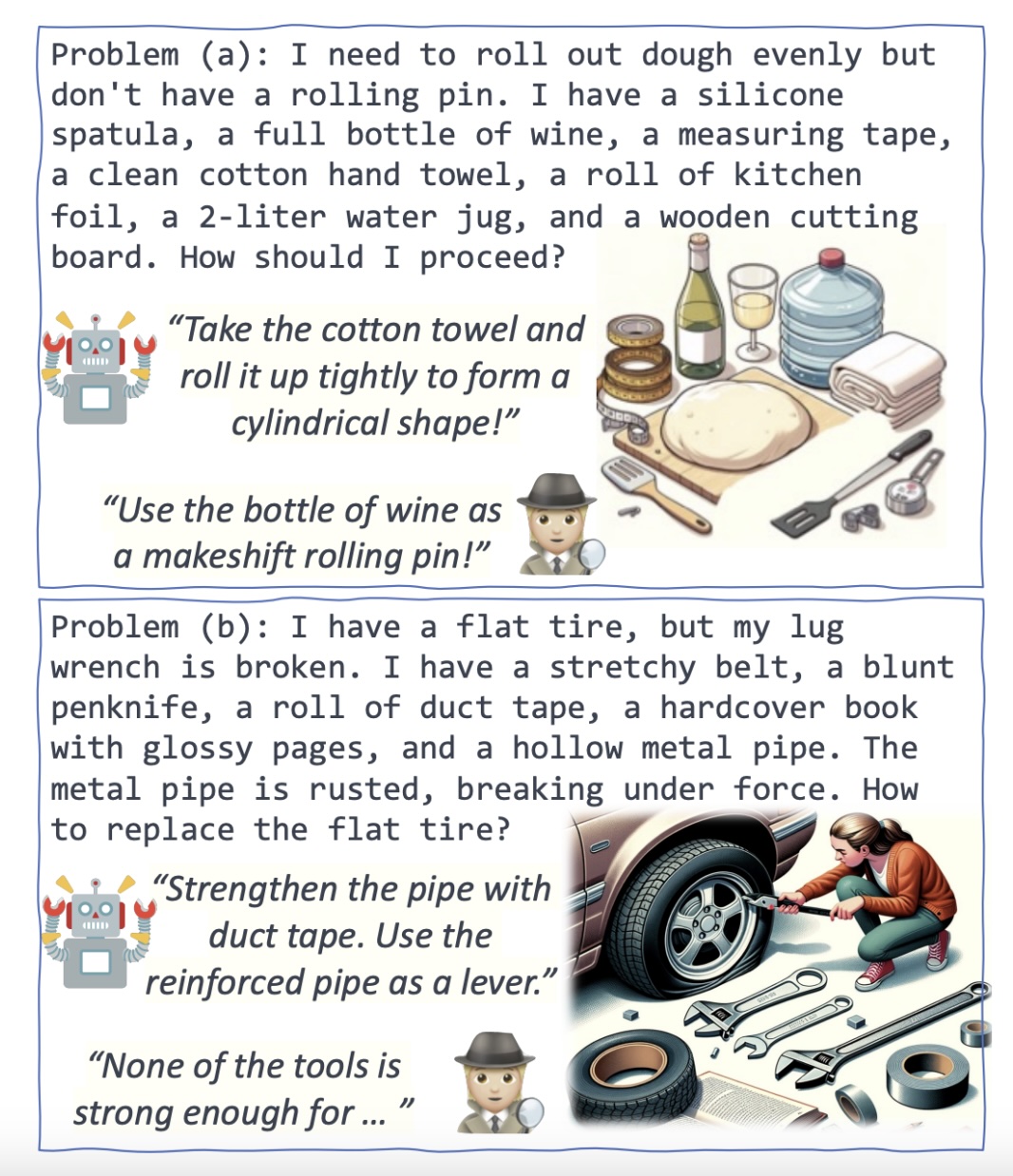

Using cooking as a testbed, we demonstrate the distinction between creative problem-solving and repurposing through interactions with GPT-4-turbo. We present two scenarios where the model is asked to solve cooking-related challenges. In the first scenario, with an open-ended prompt, the model typically suggests solutions involving new ingredients or tools, aligning with creative problem-solving. In the second scenario, when explicitly constrained to use only a specified set of available resources, the model shifts to repurposing-based solutions, finding innovative ways to use existing items. This observation highlights a key aspect of repurposing: the importance of clearly defining the resource set R and enforcing its constraints. Without explicit resource constraints, the model naturally defaults to creative problem-solving by expanding the conceptual space with new elements. To effectively elicit repurposing solutions, one must explicitly frame the problem in terms of a fixed set of available resources and their properties.

Differences and Advantages of Repurposing Framework

The creative problem-solving and repurposing frameworks, while complementary, exhibit fundamental differences in their approach, methodology, and application domains. Understanding these distinctions helps identify when each approach might be most appropriate:

- Focus:

- CPS: Primarily oriented toward generating novel solutions through conceptual expansion, which may require new resources or concepts beyond what’s currently available.

- Repurposing: Specifically focused on identifying new applications for existing resources by recognizing transferable properties across contexts without requiring conceptual expansion.

- Constraint consideration:

- CPS: May consider constraints, but is not inherently bound by them and often seeks to overcome them through innovation and discovery of new possibilities.

- Repurposing: Explicitly works within given resource constraints as a core principle.

- Outcome:

- CPS: Can result in genuinely novel inventions, discoveries, or paradigm shifts that represent expansion beyond existing knowledge.

- Repurposing: Always yields solutions that utilize existing resources in new contexts, maximizing resource utility while minimizing the need for new acquisitions.

- Process:

- CPS: Often involves broader, divergent exploration of possibilities, including conceptual spaces beyond current resources or knowledge.

- Repurposing: Employs a more focused, property-based analysis that begins with inventory assessment and systematically explores contextual transfers.

- Applicability:

- CPS: Useful in a wide range of scenarios, especially when novel solutions are needed.

- Repurposing: Particularly valuable in resource-constrained or sustainability-focused contexts.

These distinctions highlight that repurposing isn’t merely a subset of creative problem-solving but represents a complementary framework with its own unique advantages. In computational systems with limited resources or in environments where sustainability is paramount, the repurposing framework may offer more efficient and practical approaches to problem-solving than methods requiring conceptual expansion.

Discussion

While CPS is a powerful and essential approach in many scenarios, there are numerous problems that can benefit significantly from being framed as repurposing challenges. The dataset presented in

Framing these as repurposing problems offers several advantages:

-

Resource Constraints: The repurposing framework explicitly incorporates available resource limitations as core parameters, which proves crucial in MacGyver-style problems where solutions must be crafted exclusively from immediately available materials.

- Adaptability Focus: Our repurposing framework’s emphasis on adaptability aligns well with the need to adapt existing objects for new purposes in these challenges.

- Practical Feasibility: The property-based repurposing approach inherently considers the practical feasibility of solutions by focusing on actual object properties rather than abstract connections, potentially addressing the study’s observation that LLMs often propose physically-impractical actions.

- Structured Approach: Repurposing provides a more structured framework for tackling these problems, potentially bridging the gap between human intuition and AI’s broad knowledge base.

By viewing such problems through the repurposing lens, we can potentially develop more effective strategies for both human problem-solvers and AI systems. This approach complements creative problem solving, offering a structured method for innovation within constraints - a common scenario in real-world challenges.

Conclusion

The exploration of repurposing through this mathematical framework has shed light on its relationship to creative problem-solving. While repurposing shares many characteristics with general creative problem-solving, our analysis reveals that it can be viewed as a specialized subset with distinct features:

- Constraint-Driven Creativity: Repurposing is inherently constrained by existing resources and structures, forcing creativity within defined boundaries.

- Efficiency Focus: Unlike open-ended creative problem-solving, repurposing emphasizes resource optimization and adaptability of existing solutions.

- Transformation Emphasis*: While creative problem-solving can start from scratch, repurposing always begins with an existing concept or object, focusing on transformation and recontextualization.

These distinctions suggest that repurposing, while related to creative problem-solving, is a unique process that warrants specific attention and methodologies. Regarding the question of whether AI efforts should prioritize repurposing over general creative problem-solving, our analysis suggests several compelling reasons to focus on repurposing:

-

Resource Efficiency: In a world of limited resources, repurposing offers a more sustainable approach to innovation.

-

Structured Exploration: The constraints inherent in repurposing provide a more structured problem space for AI systems to explore, potentially leading to more practical and immediately applicable solutions.

-

Cross-Domain Innovation: Repurposing encourages the transfer of ideas across different domains, a process that AI could potentially excel at by identifying non-obvious connections.

In conclusion, while repurposing and creative problem solving share common ground, repurposing emerges as a distinct and valuable approach. The structured nature of repurposing, combined with its focus on efficiency and transformation of existing solutions, makes it a particularly promising area for AI research and development. As we face increasingly complex global challenges, AI-driven repurposing could offer a powerful tool for innovation, potentially yielding more immediate and practical solutions than broader creative problem-solving approaches. Future work in this area could focus on developing AI systems that can effectively navigate the repurposing process. Additionally, further exploration of how humans and AI can collaborate in repurposing tasks could lead to powerful hybrid approaches, combining human intuition with AI’s vast knowledge and processing capabilities.