Reexamining the Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty Dichotomy

When discussing uncertainty estimates for the safe deployment of AI agents in the real world, the field typically distinguishes between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty. This dichotomy may seem intuitive and well-defined at first glance, but this blog post reviews examples, quantitative findings, and theoretical arguments that reveal that popular definitions of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties directly contradict each other and are intertwined in fine nuances. We peek beyond the epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty dichotomy and reveal a spectrum of uncertainties that help solve practical tasks especially in the age of large language models.

The Fuzzy Clouds of Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty

When asking insiders and outsiders of the uncertainty quantification field, the terms aleatoric uncertainty and epistemic uncertainty seem to have an agreed-upon meaning. Epistemic uncertainty is reducible uncertainty, such as when a model could be trained with more data from new regions of the input manifold to produce more definite outputs. Aleatoric uncertainty is irreducible uncertainty, when the data itself is too noisy or lacks features to make predictions that come without a risk of error, regardless of how good the model is. These terms date back to philosophical papers from the 17th century

| School of Thought | Main Principle |

|---|---|

| Epistemic Uncertainty as Number of Possible Models | Epistemic uncertainty is how many models a learner believes to be fitting for the data. |

| Epistemic Uncertainty via Disagreement | Epistemic uncertainty is how much the possible models disagree about the outputs. |

| Epistemic Uncertainty via Density | Epistemic uncertainty is high if we are far from seen examples and low within the train dataset. |

| Epistemic Uncertainty as Leftover Uncertainty | Epistemic uncertainty is the (estimated) overall uncertainty minus the (estimated) aleatoric uncertainty. |

| Aleatoric Uncertainty as Bayes-optimal Model | Aleatoric uncertainty is the risk that the best model inside a model class still has, assuming infinite data. |

| Aleatoric Uncertainty as Pointwise Ground-truth Variance | Aleatoric uncertainty is the variance that the output variable has on each input point, and errors because the model class is too simple is not part of it. |

| Aleatoric and Epistemic as Labels of the Practitioner | Aleatoric and epistemic are just terms with which practitioners communicate which uncertainties they intend to reduce and which not. |

| Source-wise Uncertainties | To reduce uncertainties, it is more important which factors cause uncertainties than which uncertainties are aleatoric or epistemic. |

| Task-wise Uncertainties | Each task requires a customized uncertainty and the performance is measured by a customized metric rather general aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties. |

It can already be seen that some of these definitions directly contradict each other. This blog post aims to guide the reader through the cloudy mist of definitions and conflicts in the recent uncertainty disentanglement literature. By a mix of examples, quantitative observations, and theoretical findings from the literature, we reach one core insight: The strict dichotomy between aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty is detrimental for many practical tasks. Instead, we provide viewpoints above the fuzzy clouds of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty. By viewing the uncertainty estimation field as uncertainty tasks and uncertainty sources, we provide the reader with a more pragmatic map of its vast landscapes. We give a particular emphasis on uncertainty types that arise in the context of large language models and chatbots, and draw avenues for future research paths that peak beyond the aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty dichotomy.

Conflicts in the Literature

Epistemic Uncertainty: Maximal or Minimal?

We start with a definition conflict that can be seen directly by example. Suppose a learner is parametrized by \(\theta\) and models a binary classification problem. In this section, we focus on only one input sample \(x \in \mathcal{X}\), so the learner is simply tasked to estimate the probability \(p \in [0, 1]\) of a Bernoulli distribution \(y\mid x \sim \text{Ber}(p)\) with the parameter \(\theta \in [0,1]\). We train the learner with some data \(\{y_n\}_{n=1}^N\), so that it forms a second-order distribution \(Q(\theta)\) that tells which parameters it finds plausible for the data. In Bayesian terms, the parameter \(\theta\) is a random variable \(\Theta\) itself. Suppose that after training, the learner concludes that there are only two possible models left that could fit the data, either \(\theta=0\) or \(\theta=1\), i.e., \(Q\) is a mixture of two Diracs. Does this reflect a state of maximal or minimal epistemic uncertainty?

There are multiple, equally grounded answers to this question. On the one hand, one can define epistemic uncertainty as a form of disagreement. For example, epistemic uncertainty is often defined from a mutual information perspective as \(\mathbb{I}_{P(y, \theta \mid x)}\left(y; \theta\right)\).

On the other hand, epistemic uncertainty can be defined based on the number of plausible models that could explain the data. For instance, Wimmer et al.

If we understand your criticism correctly, it boils down to a concept of disagreement rather than ignorance and lack of knowledge, which is what epistemic uncertainty is actually supposed to capture. Please note that your suggestion of a second-order distribution ... https://t.co/qetef7YQra

— Lisa Wimmer (@WmLisa) August 1, 2024

Besides these two conflicting schools of thought, there is a third one that defines epistemic uncertainty as the (latent) density of the training data

In conclusion, there are multiple schools of thought on what epistemic uncertainty really is, and each of them has equally well-grounded justifications. These approaches conflict with each other even in the above simplistic example, which is both entirely theoretical (leaving estimation errors of the epistemic estimators aside) and inside one fixed context (the input and output spaces \(\mathcal{X}, \mathcal{Y}\) are fixed, and the model class covers all possible data-generating processes). We will see next that these conflicts do not only occur with epistemic uncertainty.

Aleatoric Uncertainty: Reducible Irreducibility

Let us expand the above example. We now regard different inputs \(x \in [0, 10]\), and use a linear model that estimates \(f(x, \theta) = p(Y=1\mid X=x, \theta)\). Recall that aleatoric uncertainty is often vaguely mentioned as the irreducible uncertainty that, even with infinite data, is impossible to improve on. But what does irreducible mean?

One can try to formalize aleatoric uncertainty as the uncertainty that even the Bayes-optimal model has

This problem is accentuated whenever epistemic uncertainty is defined as the “remaining” uncertainty after subtracting aleatoric from predictive uncertainty

Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty Are Intertwined

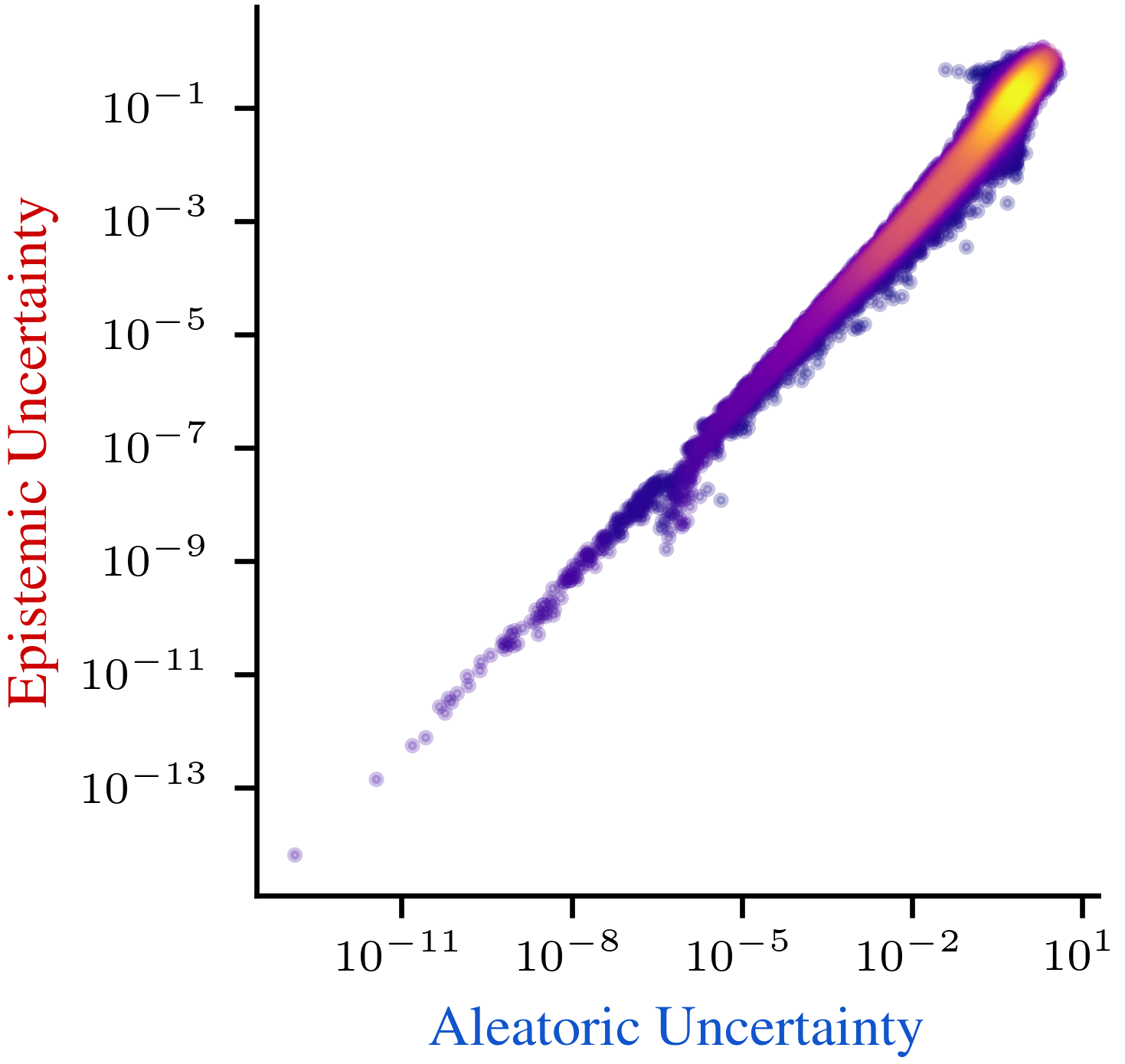

If aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty were distinct, orthogonal categories (and there were no further categories), they could be added up to obtain predictive uncertainty. This is proposed by information-theoretical decompositions

At the first look, the two summands resemble aleatoric uncertainty (average entropy of the prediction) and epistemic uncertainty (disagreement between ensemble members). However, Mucsányi et al.

One may argue that these experimental observations are due to confounded approximation errors and that additive disentanglement is still possible in theory. However, Gruber et al.

[A]leatoric uncertainty estimation is unreliable in out-of-distribution settings, particularly for regression, with constant aleatoric variances being output by a model. [...] [A]leatoric and epistemic uncertainties interact with each other, which is unexpected and partially violates the definitions of each kind of uncertainty. — Valdenegro-Toro and Mori

These practical and theoretical observations lead to the same conclusion, namely, that aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty cannot be split exactly. Most evidence on this is on additive splits, but the latter arguments on epistemic approximation uncertainty about the aleatoric uncertainty estimator (

From Epistemic to Aleatoric and Back: Uncertainties and Chatbots

The concepts of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty become even more blurred when we go towards agents that interact with the real world. A chatbot is able to ask follow-up questions, which changes the features \(x\) responsible for the answer \(y\). Let us denote a conversation up to a certain time point \(t\in \mathbb{N}\) as some (concatenated) string \(x_t\), and let us assume, for simplicity, that the question of the conversation remains the same, so that the true answer distribution \(P(Y)\) does not change with \(t\). Now that the information that the chatbot gathered in a conversation \(x_t\) is dynamic in \(t\), is the uncertainty about \(Y\) aleatoric or epistemic?

One can argue to only look at fixed time points \(t\) in the conversation, where the information \(x_t\) collected up to this point poses an irreducible uncertainty for predicting $y$, hence the agent experiences aleatoric uncertainty. Its reduction via follow-up questions would just be a paradoxical illusion as the point \(x_t\) in the input space \(\mathcal{X}\) for which we calculate the (possibly lower) aleatoric uncertainty changes. However, one can equally argue that – even when still only looking at one fixed point \(x_t\) – it is possible to gain more information in future time steps by further questions or retrieval augmentation

Der Kiureghian and Ditlevsen

Beyond the Aleatoric/Epistemic Dichotomy

The recent findings presented above suggest that research should not focus on binarizing uncertainties into either aleatoric or epistemic, as if there were some ground-truth notions of it. So what do we suggest future researchers instead?

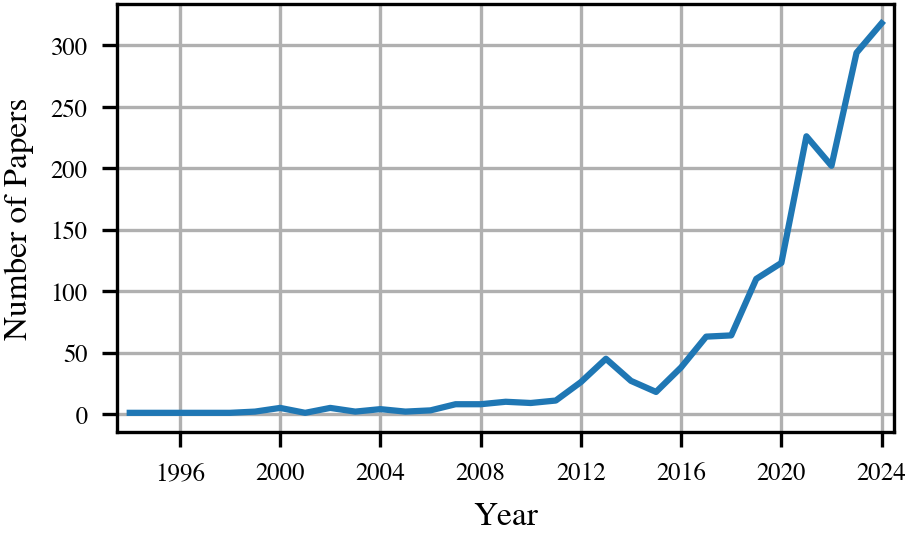

First, we want to point out what we do not intend. We do not suggest deleting the words “aleatoric” and “epistemic” from our vocabularies. As touched upon in the introduction, they serve a good purpose in roughly communicating what an uncertainty’s goal is and, as the plot below shows, their popularity is on an all-time high. However, after using one of those two umbrella terms, we propose to relentlessly follow-up by defining what exactly is meant, and what exactly one intends to solve with a specific uncertainty estimator. Maybe, the most basic common denominator we propose to the field is to spare a couple of characters: To start talking about aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties, reflecting that both are broad regions with many subfields and overlaps. This view is rising in recent uncertainty papers, as put by Gruber et al.

[A] simple decomposition of uncertainty into aleatoric and epistemic does not do justice to a much more complex constellation with multiple sources of uncertainty. — Gruber et al.

Our main suggestion for theoreticians is to keep the challenges in mind that practitioners face. Instead of binarizing uncertainties into two categories, and trying to estimate one ground-truth for each (if it exists), we suggest to pragmatically view uncertainties from the tasks they are trying to solve. This opens three new research avenues.

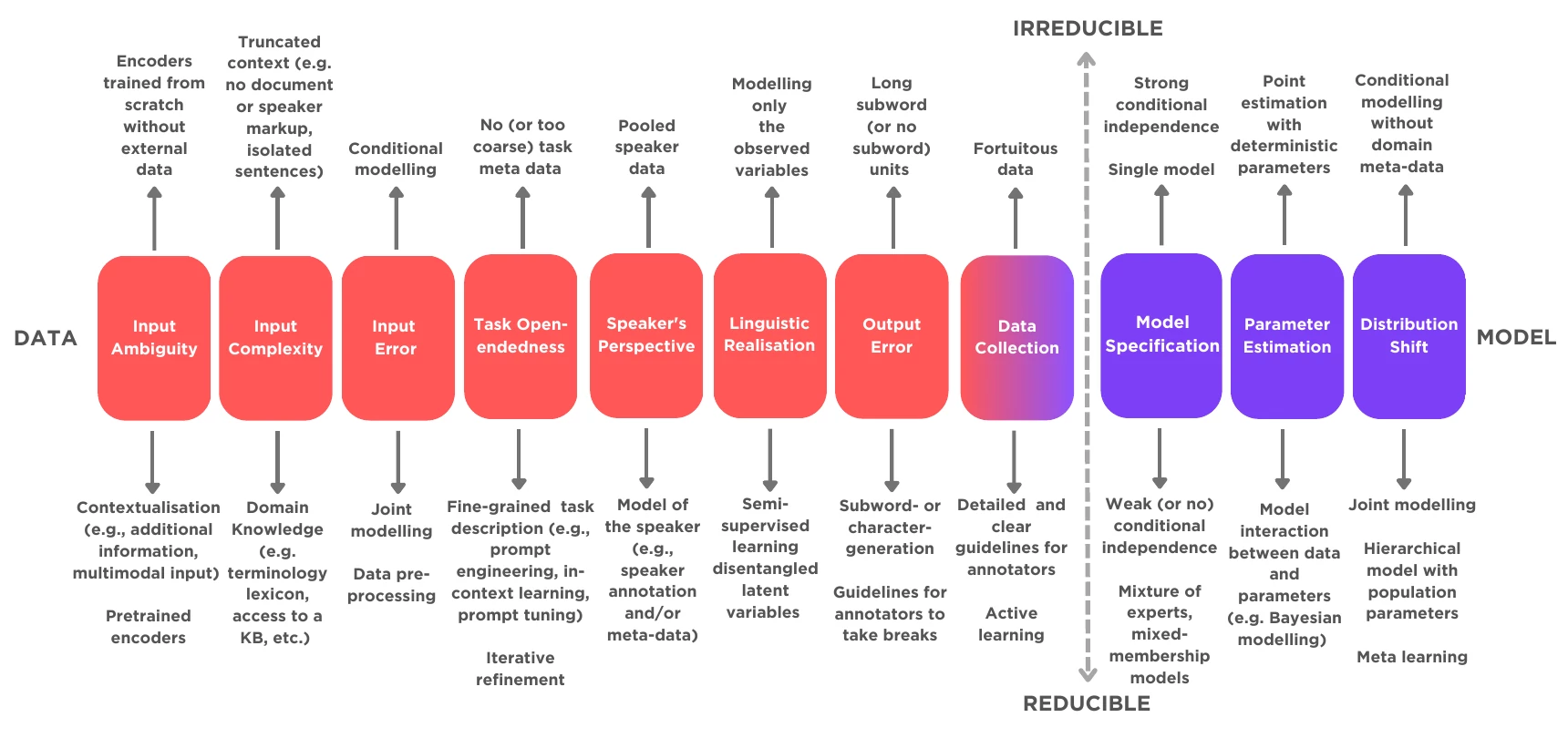

The first prospect is reflect on the sources of uncertainties that can be tackled to reduce the overall uncertainty

The second research avenue is to reflect on the metrics that uncertainty estimators are evaluated by, and thus developed along. Mucsányi et al.

The third path for future research may explore the various types of uncertainties that arise with the application of large language models and text-to-speech systems, regardless of whether they should be called aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties. One example that has gained recent attention is uncertainty arising from expressing the same factoid in different equivalent grammatical forms, known as semantic entropy

Conclusion

This blog post critically assessed the recent literature in aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty decompositions. Through our examples and references to quantitative and theoretical findings in the literature, we have shown that binarizing uncertainties into either aleatoric or epistemic can create conflicts, and that a strict dichotomy is not supportive for many future applications related to large language models. We anticipate that our recommendations – to initiate uncertainty quantification research from specific application contexts and to investigate appropriate theoretical frameworks and types of uncertainty pertinent to those contexts – will inspire future researchers to develop more practically oriented and nuanced uncertainty measures. By moving beyond the traditional dichotomy of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty and considering specific practical categories such as model bias, robustness, structural uncertainty, or computational/generation uncertainty such as in NLP applications, researchers can develop comprehensive uncertainty quantification methods tailored to real-world applications. This approach not only aligns uncertainty measures more closely with the practical needs of specific domains but also contributes to the creation of more robust predictive models and more informed decision-making processes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kajetan Schweighofer and Bálint Mucsányi. The exchanges on what the true nature of aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty is, if there is any at all, have motivated and shaped this work.