Pitfalls of Evidence-Based AI Policy

Evidence is of irreplaceable value to policymaking. However, there are systematic biases shaping the evidence that the AI community produces. Holding regulation to too high an evidentiary standard can lead to systmatic neglect of certain risks. If the goal is evidence-based AI policy, the first regulatory objective must be to actively facilitate the process of identifying, studying, and deliberating about AI risks.

At this very moment, I say we sit tight and assess.

Abstract

Nations across the world are working to govern AI. However, from a technical perspective, there is uncertainty and disagreement on the best way to do this. Meanwhile, recent debates over AI regulation have led to calls for “evidence-based AI policy” which emphasize holding regulatory action to a high evidentiary standard. Evidence is of irreplaceable value to policymaking. However, holding regulatory action to too high an evidentiary standard can lead to systematic neglect of certain risks. In historical policy debates (e.g., over tobacco ca. 1965 and fossil fuels ca. 1985) “evidence-based policy” rhetoric is also a well-precedented strategy to downplay the urgency of action, delay regulation, and protect industry interests. Here, we argue that if the goal is evidence-based AI policy, the first regulatory objective must be to actively facilitate the process of identifying, studying, and deliberating about AI risks. We discuss a set of 15 regulatory goals to facilitate this and show that Brazil, Canada, China, the EU, South Korea, the UK, and the USA all have substantial opportunities to adopt further evidence-seeking policies.

How Do We Regulate Emerging Tech?

Recently, debates over AI governance have been ongoing across the world. A common underlying theme is the challenge of regulating emerging technologies amidst uncertainty about the future. Even among people who strongly agree that it is important to regulate AI, there is sometimes disagreement about when and how. This uncertainty has led some researchers to call for “evidence-based AI policy.”

“Nope, I am against evidence-based policy.”

See how awful that sounds? This highlights a troublesome aspect of how things are sometimes framed. Of course, evidence is indispensable. But there is a pitfall of holding policy action to too high an evidentiary standard:

As we will argue, focusing too much on getting evidence before we act can paradoxically make it harder to gather the information we need.

A Broad, Emerging Coalition

Recently, there have been a number of prominent calls for evidence-based AI policy. For example, several California congressmembers and Governor Gavin Newsom recently argued against an AI regulatory bill in California by highlighting that it was motivated by mitigating future risks that have not been empirically observed:

There is little scientific evidence of harm of ‘mass casualties or harmful weapons created’ from advanced models.

— Zoe Lofgren et al. in an open letter to Gavin Newsom

[Our] approach…must be based on empirical evidence and science…[we need] AI risk management practices that are rooted in science and fact.

Others in Academia have echoed similar philosophies of governing AI amidst uncertainty. For example, in their book AI Snake Oil

The whole idea of estimating the probability of AGI risk is not meaningful…We have no past data to calibrate our predictions.

— Narayanan and Kapoor (2024), AI Snake Oil

They follow this with an argument against the precautionary principle

Meanwhile, Jacob Helberg, a senior adviser at the Stanford University Center on Geopolitics and Technology, has argued that there just isn’t enough evidence of AI discrimination to warrant policy action.

This is a solution in search of a problem that really doesn’t exist…There really hasn’t been massive evidence of issues in AI discrimination.

— Jacob Helberg on priorities for the current US presidential administration

And Martin Casado, a partner at Andreesen Horowitz, recently argued in a post that we should hold off on taking action until we know the marginal risk:

We should only depart from the existing regulatory regime, and carve new ground, once we understand the marginal risks of AI relative to existing computer systems. Thus far, however, the discussion of marginal risks with AI is still very much based on research questions and hypotheticals.

— Casado (2024), Base AI Policy on Evidence, Not Existential Angst

And finally, the seventeen authors of a recent article titled, A Path for Science- and Evidence-Based AI Policy, argue that:

AI policy should be informed by scientific understanding…if policymakers pursue highly committal policy, the…risks should meet a high evidentiary standard.

— Bommasani et al. (2024), A Path for Science‑ and Evidence‑based AI Policy

Overall, the evidence-based AI policy coalition is diverse. It includes a variety of policymakers and researchers who do not always agree with each other. We caution against developing a one-dimensional view of this coalition or jumping to conclusions from quotes out of context. However, this camp is generally characterized by a desire to avoid pursuing highly committal policy absent compelling evidence.

A Vague Agenda?

Calls for evidence-based AI policy are not always accompanied by substantive recommendations. However, Bommasani et al. (2024)

Milestone 1: A taxonomy of risk vectors to ensure important risks are well-represented

Milestone 2: Research on the marginal risk of AI for each risk vector

Milestone 3: A taxonomy of policy interventions to ensure attractive solutions are not missed

Milestone 4: A blueprint that recommends candidate policy responses to different societal conditions

These milestones are extremely easy to agree with. Unfortunately, they are also unworkably vague. It is unclear what it would mean for them to be accomplished. In fact, for these milestones, it is not hard to argue that existing reports reasonably meet them. For example, the AI Risk Repository

These milestones are an encouraging call to actively improve our understanding. However, absent more precision, we worry that similar arguments could be misused as a form of tokenism to muddy the waters and stymie policy action. In the rest of this post, we will argue that holding regulatory action to too high an evidentiary standard can paradoxically make it harder to gather the information that we need for good governance.

The Evidence is Biased

In its pure form, science is a neutral process. But it is never done in a vacuum. Beneath the cloak of objectivity, there are subjective human beings working on problems that were not randomly selected

Selective Disclosure

In February 2023, Microsoft announced Bing Chat, an AI-powered web browsing assistant. It was a versatile, semi-autonomous copilot to help users browse the web. It was usually helpful, but sometimes, it went off the rails. Users found that it occasionally took on shockingly angsty, deceptive, and outright aggressive personas. It would go so far as to sometimes threaten users chatting with it. Rest assured, everyone was fine. Bing Chat was just a babbling web app that could not directly harm anyone. But it offers a cautionary tale. Right now, developers are racing to create increasingly agentic and advanced AI systems

Following the Bing Chat incidents, Microsoft’s public relations strategy focused on patching the issues and moving on. To the dismay of many AI researchers, Microsoft never published a public report on the incident. If Microsoft had nothing but humanity’s best interests at heart, it could substantially help researchers by reporting on the technical and institutional choices that led to Bing Chat’s behaviors. However, it’s just not in their public relations interests to do so.

Historically, AI research and development has been a very open process. For example, code, models, and methodology behind most state-of-the-art AI systems were broadly available pre-2020. More recently, however, developers like Microsoft have been exercising more limited and selective transparency

Easy vs. Hard-to-Measure Impacts

The scientific process may be intrinsically neutral, but not all phenomena are equally easy to study. Most of the downstream societal impacts of AI are difficult to accurately predict in a laboratory setting. The resulting knowledge gap biases purely evidence-based approaches to neglect some issues simply because they are difficult to study.

Thoroughly assessing downstream societal impacts requires nuanced analysis, interdisciplinarity, and inclusion…there are always differences between the settings in which researchers study AI systems and the ever-changing real-world settings in which they will be deployed.

— Bengio et al. (2024), International Scientific Report on the Safety of Advanced AI

Differences in the measurability of different phenomena can cause insidious issues to be be neglected. For instance, compare explicit and implicit social biases in modern language models. Explicit biases from LLMs are usually easy to spot. For example, it is relatively easy to train a language model against expressing harmful statements about a demographic group. But even when we do this to language models, they still consistently express more subtle biases in the language and concept associations that they use to characterize different people

Meanwhile, benchmarks provide the main scaffolding behind research progress in AI

Precedented vs. Unprecedented Impacts

In the history of safety engineering, many major system failures follow a certain story

Ingroups vs. Outgroups

The AI research community does not represent humanity well. For example, AI research is dominated by White and Asian

Since AI technologies are mostly conceived and developed in just a handful of countries, they embed the cultural values and practices of these countries.

– Prabhakaran et al. (2022), Cultural Incongruities in Artificial Intelligence

For example, AI ethics researchers have contrasted India and the West to highlight the challenges posed by cultural homogeneity in the research community. In the West, societal discussions around fairness can, of course, be very nuanced, but they reflect Western experiences and are often characterized by a focus on race and gender politics. In India, however, the axes of social disparity are different and, in many ways, more complex. For example, India has 22 official languages, a greater degree of religious conflict, and a historical Caste system. This has led researchers to argue that the AI community is systematically poised to neglect many of the challenges in India and other non-Western parts of the world

The Culture and Values of the AI Research Community

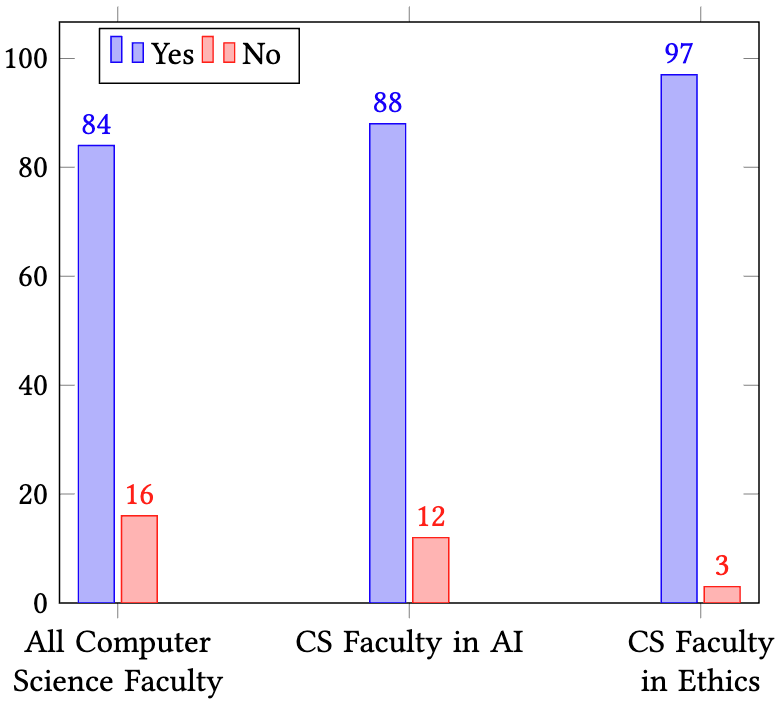

Perhaps the most important ingroup/outgroup contrast to consider is the one between the AI research community and the rest of humanity. It is clear that AI researchers do not demographically represent the world

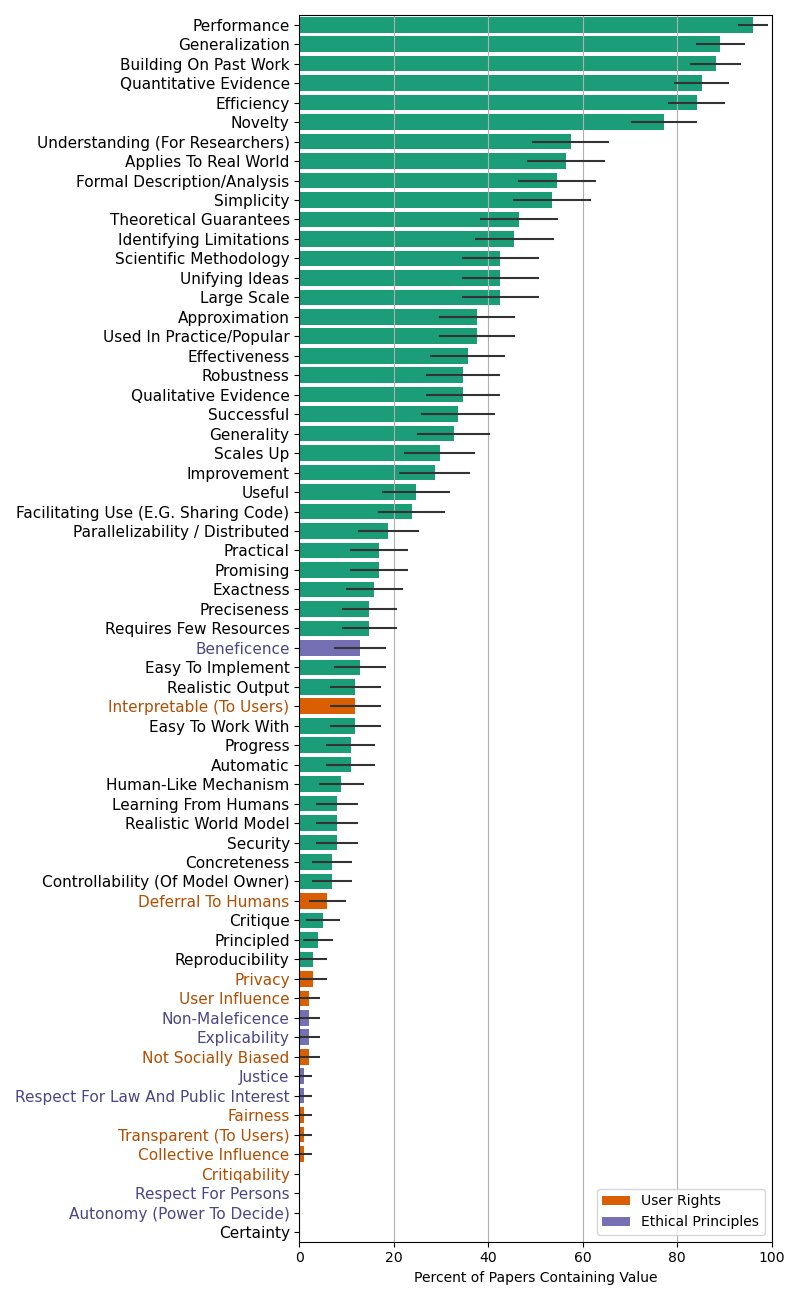

In their paper, The Values Encoded in Machine Learning Research, Birhane et al. (2021)

They found an overwhelming predominance of values pertaining to system performance (green) over the other categories of user rights and ethical principles. This suggests that the AI community may be systematically predisposed to produce evidence that will disproportionately highlight the benefits of AI compared to its harms.

Industry Entanglement with Research

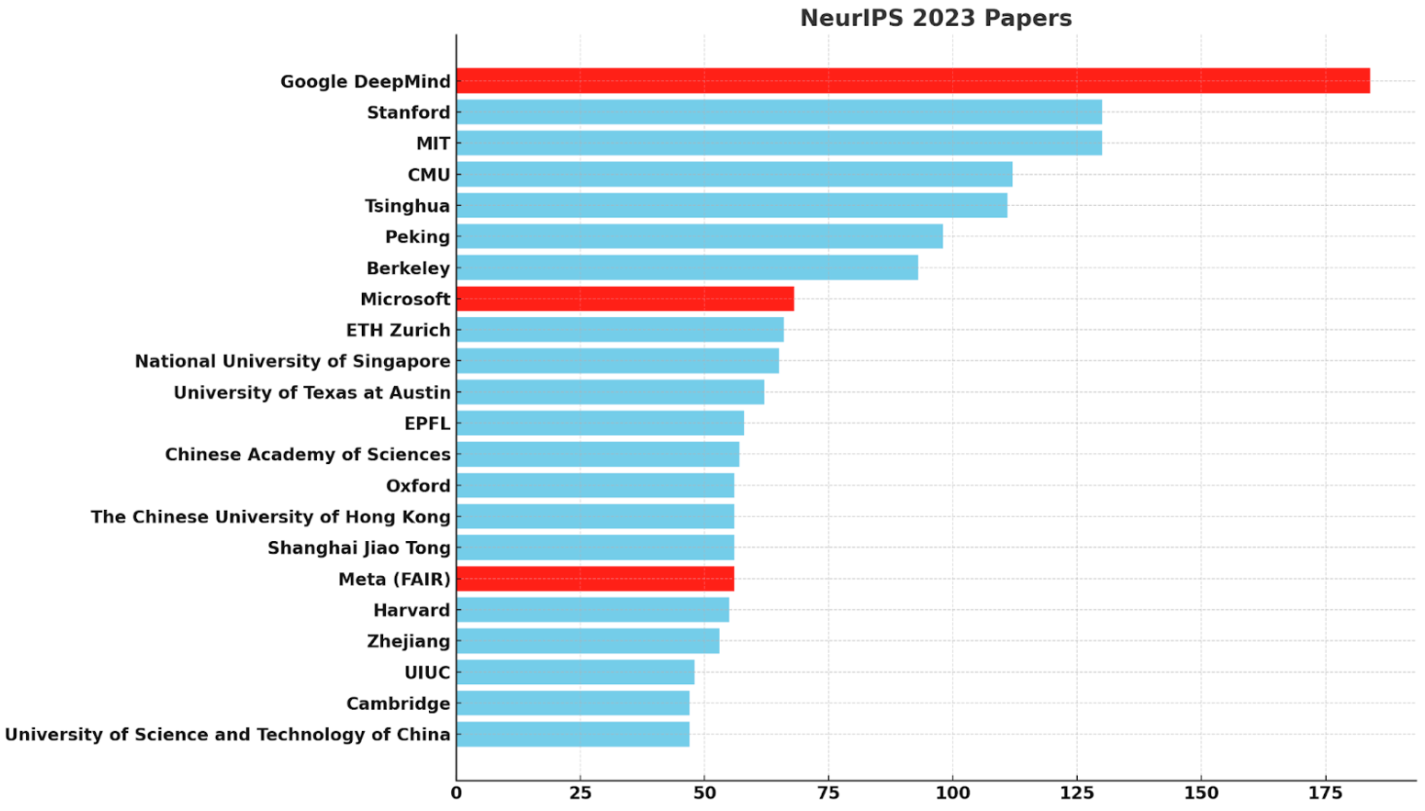

Who is doing the AI research? Where is the money coming from? In many cases, the answer to both is the tech companies that would be directly affected by regulation. For instance, consider last year’s NeurIPS conference. Google DeepMind, Microsoft, and Meta all ranked in the top 20 organizations by papers accepted:

Meanwhile, other labs like OpenAI and Anthropic may not publish as many papers, but they nonetheless have highly influential work (e.g.,

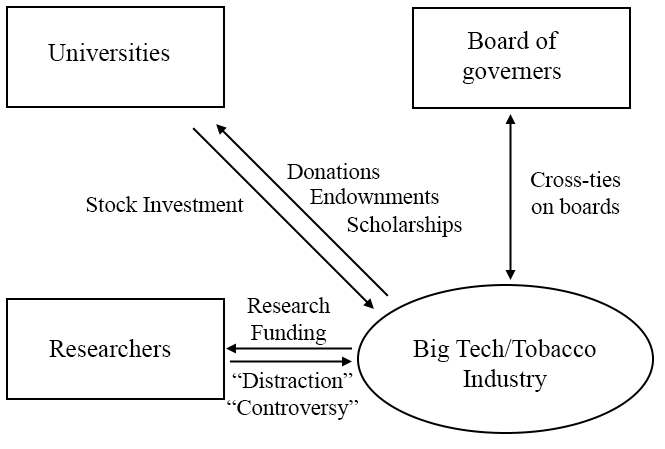

The reach of industry labs into the research space involves more than just papers. AI academia’s entanglement with industry runs deep:

Imagine if, in mid-December of 2019, over 10,000 health policy researchers made the yearly pilgrimage to the largest international health policy conference in the world. Among the many topics discussed…was how to best deal with the negative effects of increased tobacco usage… Imagine if many of the speakers who graced the stage were funded by Big Tobacco. Imagine if the conference itself was largely funded by Big Tobacco.

– A discussion alluding to the NeurIPS 2019 conference from Abdalla and Abdalla (2020), The Grey Hoodie Project Big Tobacco, Big Tech, and the threat on academic integrity

When a powerful industry is facing regulation, it is in its interest to pollute the evidence base and public discussion around it in order to deny risks and delay action. A key way that this manifests is with assertions that we need more evidence and consensus before we act.

Is it any wonder that those who benefit the most from continuing to do nothing emphasize the controversy among scientists and the need for continued research?

– Giere et al. (2006), Understanding Scientific Reasoning

A common ‘Deny and Delay Playbook’ has been used in historical policy debates to delay meaningful regulation until long after it was needed. A common story has played out in debates around tobacco, acid rain, the ozone layer, and climate change

Any evidence can be denied by parties sufficiently determined, and you can never prove anything about the future; you just have to wait and see.

– Oreskes and Conway (2010), Merchants of Doubt

To illustrate this, we invite the reader to speculate about which of these quotes came from pundits recently discussing AI regulation and which came from merchants of doubt for the tobacco and fossil fuel industries.

To see an example of Big Tech entangled with calls for “evidence-based AI policy,” we need to look no further than Bommasani et al. (2024): A Path for Science‑ and Evidence‑based AI Policy

Lacking Evidence as a Reason to Act

So if the evidence is systematically biased? What do we do? How do we get more, better evidence?

Substantive vs. Process Regulation

We argue that a need to more thoroughly understand AI risks is a reason to pass regulation – not to delay it. To see this, we first need to understand the distinction between “substantive” regulation and “process” regulation. For our purposes, we define them as such:

- Substantive regulation limits what things developers can do with their AI systems.

- Process regulation limits how developers do what they do with their AI systems.

These two categories of regulations do not only apply to AI. In the food industry, for example, ingredient bans are substantive regulations while requirements for nutrition facts are process regulations. Process regulations usually pose significantly lower burdens and downsides than substantive ones. The key reason why this distinction is important is that, as we will argue:

Depending on whether we are considering substantive or process regulation, the argument can go different ways. To see an example, let’s consider some recent discussions on cost and compute thresholds in AI regulations.

In Defense of Compute and Cost Thresholds in AI Regulation

Some AI policy proposals set cost and compute thresholds such that, if a system’s development surpasses these, it would be subject to specific requirements. Some researchers have rightly pointed out that there are hazards associated with this; cost and compute can be poor proxies for societal risk

These are important and needed points about the limitations of cost and compute thresholds. For example, suppose that we are considering substantive regulations that prevent deploying certain models in certain ways. In this case, we would need careful cost-benefit analysis and the ability to adapt regulatory criteria over time. But until we have government agencies who are capable of performing high-quality evaluations of AI systems’ risks, cost and compute thresholds may be the only tenable proxy available.

In the case of process regulation, there is often a lack of substantial downside. For example, consider policies that require developers to register a system with the government if its development exceeds a cost or compute threshold. Compared to inaction, the upside is a significantly increased ability of the government to monitor the frontier model ecosystem. As for the downside? Sometimes certain companies will accidentally be required to do more paperwork than regulators may have intended. Compared to the laundry list of societal-scale risks from AI

We Can Pass Evidence-Seeking Policies Now

It is important to understand the role of process regulation in helping us to get evidence, especially since governments often tend to underinvest in evidence-seeking during institutional design

15 Evidence-Seeking AI Policy Objectives

Here, we outline a set of AI regulatory goals related to institutions, documentation, accountability, and risk-mitigation practices designed to produce evidence. Each is process-based and fully risk-agnostic. We argue that the current lack of evidence about AI risks is not a reason to delay these, but rather, a key reason why they are useful.

- AI governance institutes: National governments (or international coalitions) can create AI governance institutes to research risks, evaluate systems, and curate best risk management practices that developers are encouraged to adhere to.

- Model registration: Developers can be required to register

frontier systems with governing bodies (regardless of whether they will be externally deployed). - Model specification and basic info: Developers can be required to document intended use cases and behaviors (e.g.,

) and basic information about frontier systems such as scale. - Internal risk assessments: Developers can be required to conduct and report on internal risk assessments of frontier systems.

- Independent third-party risk assessments: Developers can be required to have an independent third-party conduct and produce a report (including access, methods, and findings) on risk assessments of frontier systems

. They can also be required to document if and what “safe harbor” policies they have to facilitate independent evaluation and red-teaming . - Plans to minimize risks to society: Developers can be required to produce a report on risks

posed by their frontier systems and risk mitigation practices that they are taking to reduce them. - Post-deployment monitoring reports: Developers can be required to establish procedures for monitoring and periodically reporting on the uses and impacts of their frontier systems.

- Security measures: Given the challenges of securing model weights and the hazards of leaks

, frontier developers can be required to document high-level non-compromising information about their security measures (e.g., ). - Compute usage: Given that computing power is key to frontier AI development

, frontier developers can be required to document their compute resources including details such as the usage, providers, and the location of compute clusters. - Shutdown procedures: Developers can be required to document if and which protocols exist to shut down frontier systems that are under their control.

- Documentation availability: All of the above documentation can be made available to the public (redacted) and AI governing authorities (unredacted).

- Documentation comparison in court: To incentivize a race to the top where frontier developers pursue established best safety practices, courts can be given the power to compare the documentation for defendants with that of peer developers.

- Labeling AI-generated content: To aid in digital forensics, content produced from AI systems can be labeled with metadata, watermarks, and notices.

- Whistleblower protections: Regulations can explicitly prevent retaliation and offer incentives for whistleblowers who report violations of those regulations.

- Incident reporting: Frontier developers can be required to document and report on substantial incidents in a timely manner.

Ample Room for Progress

As we write this in February 2025, parallel debates over AI safety governance are unfolding across the world. There are a number of notable existing and proposed policies.

- 🇧🇷 Brazil has recently introduced drafts of Bill No. 2338 of 2023

(proposed) on regulating the use of Artificial Intelligence, including algorithm design and technical standards. - 🇨🇦 Canada recently established an AI Safety Institute (exists), and its proposed AI and Data Act

(proposed) is currently under consideration in House of Commons Committee. - 🇨🇳 China has enacted its Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Internet Information Services

(enacted), Provisions on the Management of Algorithmic Recommendations in Internet Information Services (enacted), and Interim Measures for the Management of Generative AI Services (enacted). There are also working drafts of a potential future ‘The Model Artificial Intelligence Law’ (proposed). - 🇪🇺 In the European Union, the EU AI Act

(enacted) was passed in March 2024, and a large undertaking to design specific codes of practice is underway. - 🇰🇷 South Korea passed the Act on the Development of Artificial Intelligence and Establishment of Trust (AI Basic Act) in December 2024.

- 🇬🇧 The UK’s AI Security Institute (exists) is currently building capacity and partnerships to evaluate risks and establish best risk-management practices. Thus far, the UK’s approach to AI regulation has been non-statutory (but new draft legislation may exist within a few months).

- 🇺🇸 In the United States, Donald Trump overturned Executive Order 14110

after assuming office in January 2025. This may or may not lead the US AI Safety Institute (exists) to be shut down. It also might permanently stall a potential policy (proposed) on model and compute reporting that the Department of Commerce proposed in response to the executive order. Meanwhile, the AI Advancement and Reliability Act (proposed) was drafted last congress and will be re-introduced this congress. Finally, the Future of AI Innovation Act (drafted) and the Preserving American Dominance in Artificial Intelligence Act (drafted) were also introduced last congress. However, as of February 2025, they are currently simply drafts.

So how are each of these countries faring?

| Brazil | Canada | China | EU | Korea | UK | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AI governance institutes | 🟨 | ✅ | 🟨 * | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| 2. Model registration | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | 🟨 * |

| 3. Model specification and basic info | 🟨 | 🟨 * | 🟨 | ✅ | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ |

| 4. Internal risk assessments | ✅ | 🟨 * | 🟨 | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 5. Independent third-party risk assessments | ❌ | ❌ | 🟨 | 🟨 | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ |

| 6. Plans to minimize risks to society | 🟨 | ❌ | 🟨 | ✅ | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ |

| 7. Post-deployment monitoring reports | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 8. Security measures | ❌ | ❌ | 🟨 | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 9. Compute usage | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ | 🟨 * |

| 10. Shutdown procedures | ✅ | 🟨 * | ❌ | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 11. Documentation availability | ❌ | 🟨 * | 🟨 | 🟨 | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ |

| 12. Documentation comparison in court | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 13. Labeling AI-generated content | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | 🟨 | 🟨 | ❌ | ❌ |

| 14. Whistleblower protections | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 15. Incident reporting | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

The Duty to Due Diligence from Discoverable Documentation of Dangerous Deeds

The objectives outlined above hinge on documentation. 2-10 are simply requirements for documentation, and 11-12 are accountability mechanisms to ensure that the documentation is not perfunctory. This is no coincidence. When it is connected to external scrutiny, documentation can be a powerful incentive-shaping force

We refer to this phenomenon as the Duty to Due Diligence from Discoverable Documentation of Dangerous Deeds – or the 7D effect. Regulatory regimes that induce this effect are very helpful for improving accountability and reducing risks. Unfortunately, absent requirements for documentation and scrutiny thereof, developers in safety-critical fields have a perverse incentive to intentionally suppress documentation of dangers. For example, common legal advice warns companies against documenting dangers in written media:

These documents may not seem bad, but in the hands of an opposing attorney these cold hard facts can [be] used to swing a judge or a jury to their side. Often the drafters of these documents tend to believe that they are providing the company with some value to the business. For example, an engineer notices a potential liability in a design so he informs his supervisor through an email. However, the engineer’s lack of legal knowledge…may later implicate the company…when a lawsuit arises.

FindLaw Attorney Writers (2016), Safe Communication: Guidelines for Creating Corporate Documents That Minimize Litigation Risks

We personally enjoyed the use of “when” and not “if” in this excerpt.

Meanwhile, there is legal precedent for companies to sometimes lose court cases when they internally communicate risks through legally discoverable media such as in Grimshaw v. Ford (1981)

Considering Counterarguments

“These 15 objectives would be too burdensome for developers.” It’s true that following protocols and producing documentation can impose burdens. However, these burdens are generally far lighter than those imposed by substantive regulations, and compliance with many of these requirements may be trivial for developers already planning to take similar actions internally. For instance, even the most potentially burdensome measures – such as risk assessments and staged deployments – are practices that major developers like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind have already publicly committed to implementing.

“It’s a slippery slope toward overreach.” A second concern is that these 15 regulatory objectives might generate information that could pave the way for future substantive regulations or liability for developers. Regulatory and liability creep are real phenomena that can harm industry interests. However, it’s important to emphasize that any progression from these objectives to future regulations or liability will ultimately depend on human decision-makers acting on evidence. Evidence is essential for society to engage in meaningful deliberation and exercise informed agency – this is the entire point of evidence-based policy. Therefore, if process-based AI regulations eventually lead to substantive regulations, it won’t be because the process regulations laid an inevitable framework. It would be because the information produced by those regulations persuaded policymakers to take further action. It would be very precarious to argue that a democratic society should be protected from its own access to information about what it is consuming.

Building a Healthier Ecosystem

Governing emerging technologies like AI is hard

[Early] studies of global warming and the ozone hole involved predicting damage before it was detected. It was the prediction that motivated people to check for damage; research was intended in part to test their prediction, and in part to stimulate action before it was too late to stop…It was too soon to tell whether or not widespread and serious…damage was occurring, but the potential effects were troubling…A scientist would be in a bit of a bind: wanting to prevent damage, but not being able to prove that damage was coming…There are always more questions to be asked.

– Oreskes and Conway (2010), Merchants of Doubt

We often hear discussions about how policymakers need help from AI researchers to design technically sound policies. This is essential. But there is a two-way street. Policymakers can do a great deal to help researchers, governments, and society at large to better understand and react to AI risks

Process regulations can lay the foundation for more informed debates and decision-making in the future. Right now, the principal objective of AI governance work is not necessarily to get all of the right substantive regulations in place. It is to shape the AI ecosystem to better facilitate the ongoing process of identifying, studying, and deliberating about risks. This requires being critical of the biases shaping the evidence we see and proactively working to seek more information. Kicking the can down the road for a lack of ‘enough’ evidence could impair policymakers’ ability to take needed action.

This lesson is sometimes painfully obvious in retrospect. In the 1960s and 70s, a scientist named S.J. Green was head of research at the British American Tobacco (BAT) company. He helped to orchestrate BAT’s campaign to deny urgency and delay action on public health risks from tobacco. However, he later split with the company, and after reflecting on the intellectual and moral irresponsibility of these efforts, he remarked:

Scientific proof, of course, is not, should not, and never has been the proper basis for legal and political action on social issues. A demand for scientific proof is always a formula for inaction and delay and usually the first reaction of the guilty. The proper basis for such decisions is, of course, quite simply that which is reasonable in the circumstance.

– S. J. Green, Smoking, Related Disease, and Causality

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for our discussions with Akash Wasil, Ariba Khan, Aruna Sankaranarayanan, Dawn Song, Kwan Yee Ng, Landon Klein, Rishi Bommasani, Shayne Longpre, and Thomas Woodside.