Multi-LLM-Agents Debate - Performance, Efficiency, and Scaling Challenges

Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) explores leveraging collaboration among multiple large language model (LLM) agents to improve test-time performance without additional training. This blog evaluates five MAD frameworks across nine benchmarks, revealing that current MAD methods fail to consistently outperform simpler single-agent strategies, even with increased computational resources. Analysis of factors such as agent configurations and debate rounds suggests that existing MAD designs fall short in fully utilizing additional inference-time computation.

Introduction

An age-old saying, two heads are better than one, encapsulates the enduring lesson that collaboration often triumphs over solitary effort. While traditionally rooted in human interactions, this principle has recently found applications in the field of large language models (LLMs)

A typical MAD works as follows: given a question, multiple LLM agents independently generate initial answers in parallel; over several rounds, agents review other agents’ answers and incorporate collective feedback to refine their answers; finally, the refined answers are aggregated to form the final answer. Besides, agents are often prompted to role-play certain personas, as shown by existing research, to be effective in stimulating critical thinking and divergent feedback. Moreover, some advanced MAD frameworks incorporate a summarizer agent to dynamically construct the final answer when simple majority voting fails, e.g., on coding tasks. Since MAD somewhat mirrors how humans engage in group discussions, it is perhaps unsurprising that MAD can improve the performance of LLMs at test time by utilizing more inference budgets and aggregating diverse information extracted from multiple agents.

However, despite the appealing intuition that deliberative collective thinking can integrate larger inference-time computation to improve the outputs, questions remain regarding its performance w.r.t. efficiency, particularly when compared to single-agent test-time computation strategies

In this blog, we take a systematic review of existing MAD frameworks, with a special focus on their performance and efficiency in comparison to widely used single-agent inference techniques, such as Chain-Of-Thought (COT)

Multi-Agent Debate Formulation

In this section, we take a brief review of existing MAD frameworks and then present a general framework that encapsulates the main ideas of MAD frameworks.

Inspired by The Society of Mind, Du et al.

Multi-Persona

While leveraging multi-persona role-playing, ChatEval

Exchange-of-Thought

AgentVerse

Current MAD methods can be represented as a directed graph, where each node corresponds to invoking an LLM agent, and each edge denotes the transfer of outcomes between agents. Specifically, the action performed at each node is defined as follows:

\[a \sim F(G(q,x;h,\theta,\beta,p))\]where $h$ denotes the chat history of the agent, $\theta$ denotes parameters of the pre-trained base model, $\beta$ denotes inference hyper-parameters, $p$ denotes formatting prompts guiding the debate, $q$ denotes the input question, and $x$ denotes the answers from other agents (output from input nodes). $G$ represents invoking an LLM agent with specified configurations and $F$ denotes the post-processing of the agent’s output. For instance, in EoT, the post-processing function $F$ assigns a confidence score to each agent’s output, enabling other agents to assess whether the outcome was generated with high confidence. The final response, $a$, is sampled from the conditional distribution $F(G(\circ; \circ))$. A digraph denoted as $G= (V,E)$ can describe the architecture of the MAD framework. A directed edge $e = (v_i, v_j) \in E$ will transmit an output $a_i$ from node $v_i$ to its subsequent neighbor $v_j$, which gives $a_i \in x_j$. If $(v_i, v_j)$ is the only incoming edge for $v_j$, then $x_j={a_i}$. Additionally, the workflow of MAD frameworks can sometimes be conditional, depending on specific outputs from certain agents. For instance, in AgentVerse, the verifier’s output may determine whether the solver is invoked again to provide a refined solution.

Evaluation

Experimental setup

Datasets We conduct our evaluation on nine widely adopted benchmarks: MMLU

Foundation models We consider representative close-sourced LLMs GPT-4o-mini

MAD methods and baselines We consider five state-of-the-art MAD frameworks in our evaluation: Multi-Agent-Debate (MAD)

Results

| GPT-4o-mini | MMLU | MMLUPRO | CommenSenseQA | ARC-Challenge | AGIEval | GSM8K | MATH | HumanEval | MBPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 65.33 ± 0.93 | 58.07 ± 0.50 | 79.47 ± 0.25 | 88.27 ± 0.41 | 63.87 ± 1.05 | 91.13 ± 0.34 | 71.67 ± 1.31 | 66.67 ± 1.15 | 58.11 ± 0.66 |

| CoT | 80.73 ± 0.34 | 62.80 ± 0.99 | 82.87 ± 0.25 | 93.53 ± 0.41 | 66.40 ± 1.30 | 93.60 ± 0.82 | 72.87 ± 1.20 | 78.05 ± 1.49 | 62.26 ± 0.84 |

| SC | 82.13 ± 0.66 | 66.27 ± 1.39 | 83.80 ± 0.28 | 93.93 ± 0.25 | 67.07 ± 0.84 | 95.67 ± 0.19 | 73.96 ± 0.54 | – | – |

| MAD | 74.73 ± 0.52 | 62.80 ± 1.02 | 80.73 ± 0.93 | 90.80 ± 0.43 | 64.33 ± 0.34 | 94.93 ± 0.34 | 75.40 ± 0.71 | 68.09 ± 1.25 | 56.94 ± 1.12 |

| MP | 75.47 ± 0.84 | 60.53 ± 1.27 | 68.07 ± 1.57 | 90.27 ± 0.25 | 61.67 ± 1.43 | 90.87 ± 0.19 | 51.87 ± 0.66 | 63.01 ± 2.30 | 45.78 ± 0.80 |

| EoT | 67.87 ± 0.41 | 61.20 ± 0.65 | 80.07 ± 0.52 | 86.40 ± 0.28 | 65.07 ± 0.66 | 94.40 ± 0.57 | 75.93 ± 1.23 | 73.78 ± 2.17 | 56.16 ± 0.49 |

| ChatEval | 79.13 ± 0.90 | 62.20 ± 0.49 | 81.07 ± 0.84 | 93.20 ± 0.28 | 68.87 ± 0.94 | 93.60 ± 0.00 | 69.36 ± 1.58 | 71.75 ± 0.76 | 53.70 ± 0.55 |

| AgentVerse | 80.40 ± 0.00 | 62.07 ± 0.52 | 80.73 ± 0.41 | 92.47 ± 0.09 | 63.87 ± 1.23 | 92.73 ± 0.50 | 64.49 ± 1.38 | 85.37 ± 0.00 | 58.88 ± 0.18 |

| Llama3.1-8b | MMLU | MMLUPRO | CommenSenseQA | ARC-Challenge | AGIEval | GSM8K | MATH | HumanEval | MBPP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 43.13 ± 1.04 | 34.27 ± 0.50 | 66.00 ± 0.16 | 81.67 ± 0.68 | 33.60 ± 0.75 | 70.40 ± 0.43 | 36.47 ± 1.09 | 54.07 ± 0.29 | 50.45 ± 1.75 |

| CoT | 57.47 ± 1.18 | 41.20 ± 1.14 | 71.13 ± 0.84 | 86.40 ± 0.99 | 46.73 ± 1.09 | 80.13 ± 1.23 | 40.13 ± 0.66 | 37.60 ± 1.52 | 43.71 ± 2.88 |

| SC | 64.96 ± 1.08 | 47.49 ± 0.08 | 74.43 ± 0.30 | 86.60 ± 1.13 | 42.47 ± 1.58 | 79.53 ± 0.68 | 30.04 ± 1.53 | – | – |

| MAD | 53.40 ± 0.28 | 36.57 ± 1.27 | 70.93 ± 0.82 | 82.00 ± 0.65 | 37.13 ± 0.47 | 63.87 ± 0.93 | 40.20 ± 0.85 | 47.56 ± 2.28 | 45.91 ± 1.15 |

| MP | 53.33 ± 2.54 | 36.44 ± 2.74 | 46.07 ± 0.62 | 61.93 ± 1.39 | 44.50 ± 1.65 | 47.60 ± 2.73 | 10.30 ± 0.93 | 24.19 ± 3.67 | 23.09 ± 1.81 |

| EoT | 48.97 ± 0.58 | 36.04 ± 0.21 | 66.15 ± 0.61 | 81.60 ± 0.43 | 33.42 ± 0.84 | 61.87 ± 2.39 | 26.61 ± 1.53 | 22.36 ± 2.07 | 23.87 ± 0.97 |

| ChatEval | 61.81 ± 0.88 | 43.56 ± 1.22 | 68.66 ± 2.62 | 84.70 ± 0.51 | 57.87 ± 1.25 | 81.13 ± 0.81 | 39.77 ± 0.54 | 41.46 ± 0.00 | 40.73 ± 1.60 |

| AgentVerse | 13.27 ± 0.47 | 20.53 ± 1.23 | 16.33 ± 1.52 | 24.60 ± 0.98 | 50.33 ± 2.49 | 5.47 ± 1.31 | 13.30 ± 1.26 | 40.24 ± 2.59 | 40.73 ± 1.60 |

We record experimental results in the tables above. Observe that most MAD frameworks are not able to achieve consistently better performances than CoT, which is a surprising outcome given the larger inference computation required by MAD frameworks. When we compare MAD frameworks to SC, which resamples from the same LLM agent to obtain the most consistent answer, we can observe that most MAD frameworks fail to surpass SC.

Specifically, we find that Multi-Persona significantly underperforms almost any other baselines. We attribute this to the fact that Multi-Persona explicitly instructs the devil agent to counter whatever the angel agent says. However, once the judge agent determines the devil’s side is correct, the angel agent has no opportunity to continue debating. This limitation results in a more pronounced performance drop, particularly when a weaker model, such as Llama 3.1-8b, is used as the base. As a result, Multi-Persona consistently performs the worst among all MAD methods across nearly all datasets. What’s more, AgentVerse performs worse using Llama3.1:8b as the foundation model, which can be explained by the fact that AgentVerse has a strict formatting requirement. Once the agent responds in an unexpected way, the debate fails. \hf{footnote about re-execution}

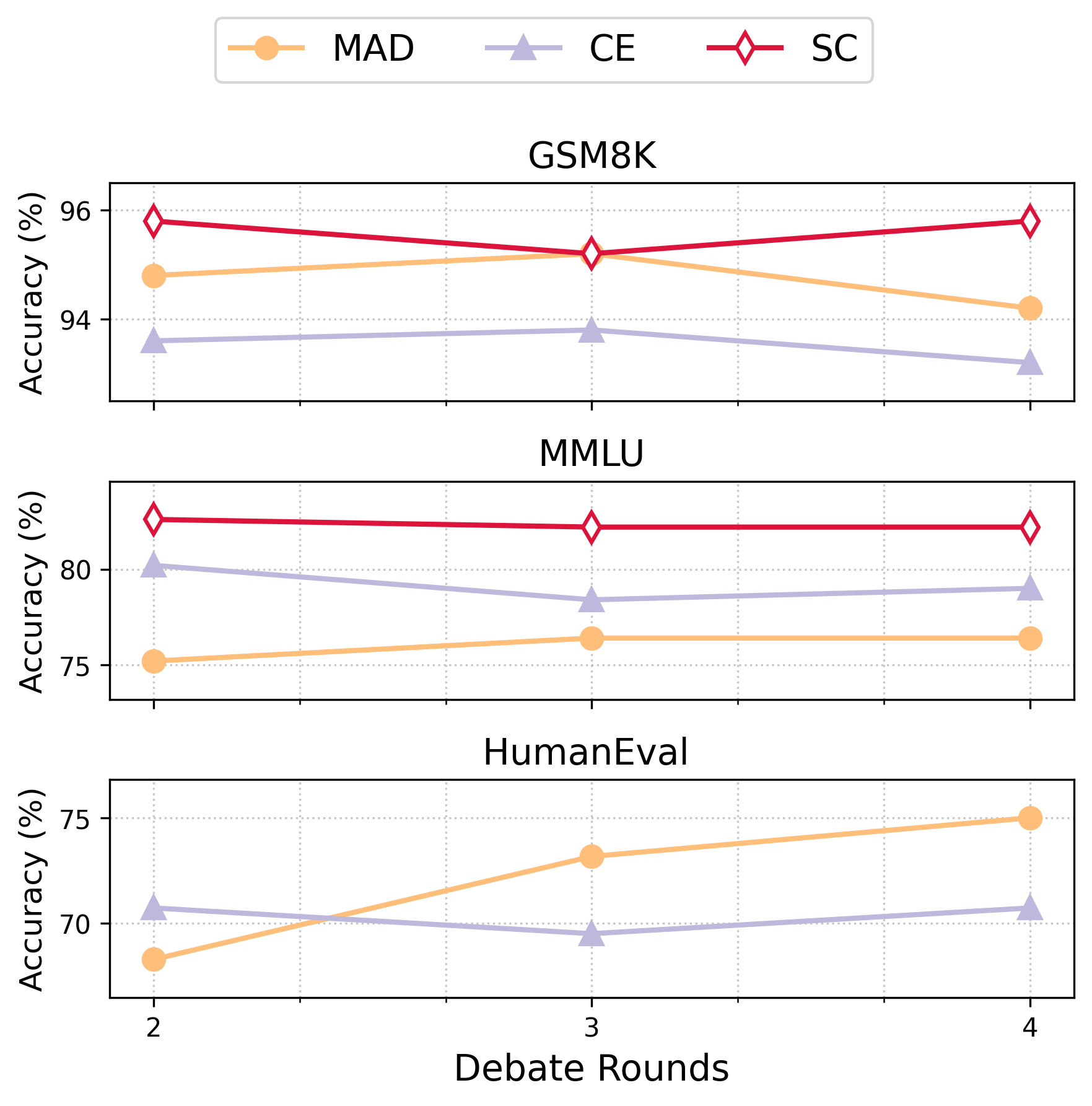

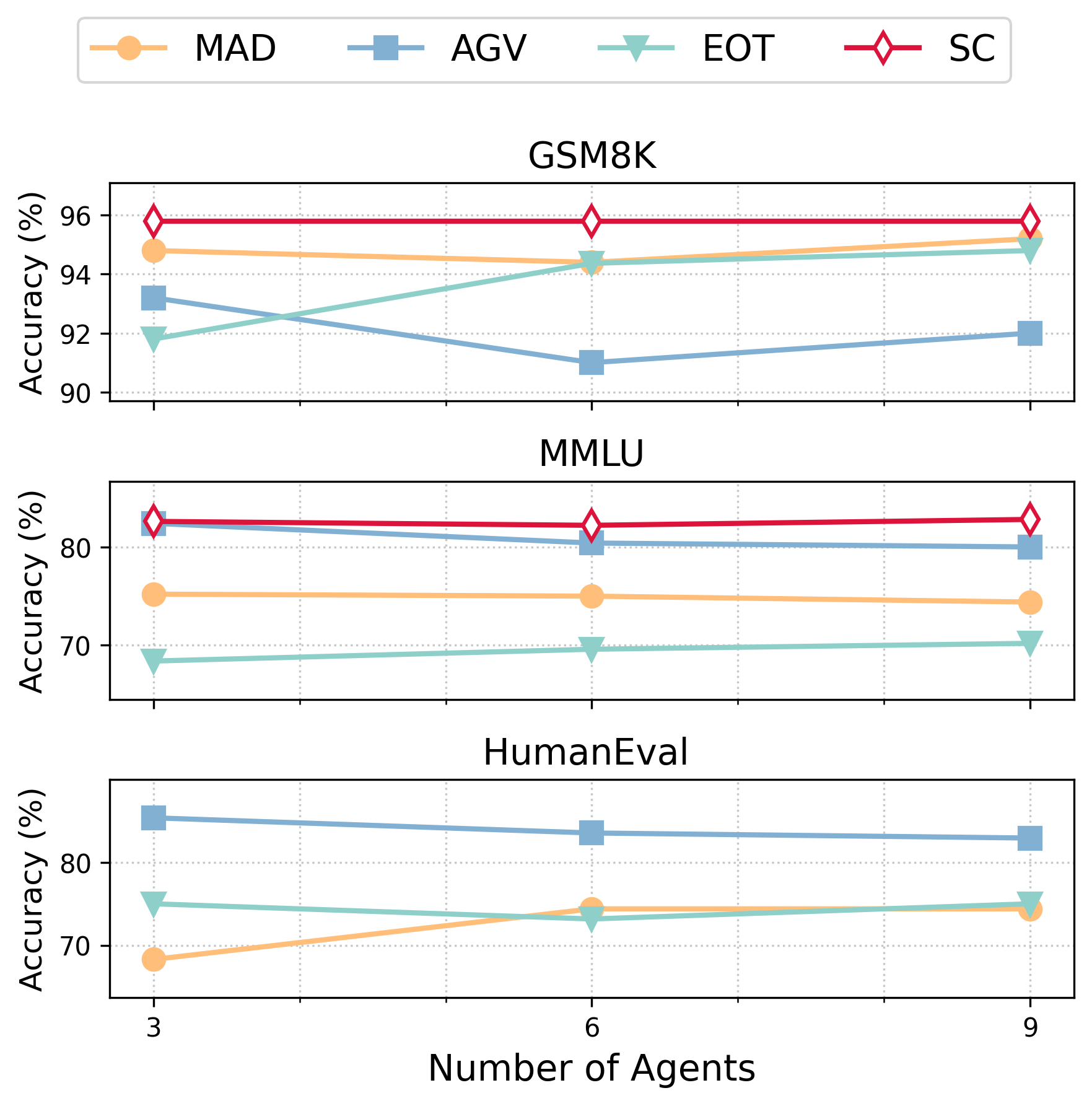

We differentiate hyperparameters in MAD frameworks to assess whether limited performances are due to suboptimal hyperparameter selection. For instance, without an appropriate configuration, MAD may fail to scale effectively. Specifically, we increase the number of agents and the number of debating rounds to allow MAD to leverage greater test-time computation in its search for better responses.

Our empirical results, presented in figures above, reveal that increasing test-time computation does not always improve accuracy. This finding suggests that current MAD frameworks may not effectively utilize larger inference budgets. We note that EOT demonstrates scalability to some extent, but we also observed that under the same conditions, EOT performs worse than other MAD methods.

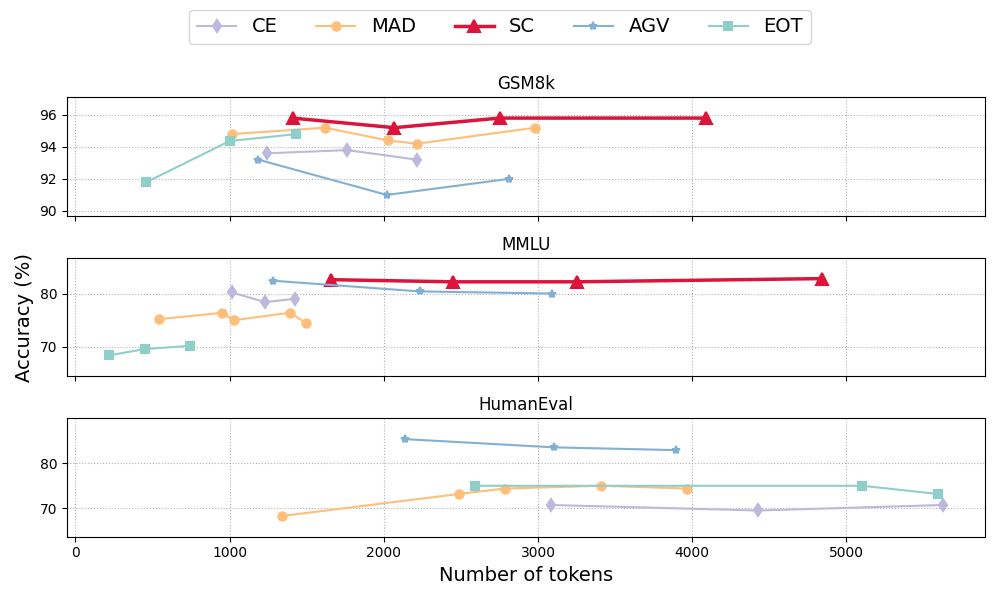

Note that prompts and response styles in MAD frameworks differ, adjusting the number of rounds and agentsn, therefore, cannot clearly reflect how well MAD frameworks utilize test-time computation. We further compare accuracy concerning consumed tokens in Figure. 2 to learn whether MAD frameworks can scale with increased test-time computation. We find that, only EOT (on GSM8k and MMLU) and MAD (on HumanEval) exhibit scalability. However, these methods are not the optimal one in both scenarios. Interestingly, while we did not observe obvious scalability in single MAD framework, we do find that the accuracy improves as the inference method (including SC) generate more tokens.

We also conduct a statistical analysis of agents’ behavior during the debating process. Specifically, we compare the outcomes of different inference methods to those of a single agent. From this comparison, four scenarios emerge: the inference method produces a consistent answer (correct or incorrect) or transforms a correct/incorrect answer into an incorrect/correct one. Ideally, the ratio of correcting wrong answers should be higher than the ratio of turning correct answers into incorrect ones to improve overall accuracy. Our results are presented in Figure. 3, where a green bar represents the number of corrected answers, and a red bar represents the number of answers erroneously reversed compared to standard single-agent prompting. Shorter red bars and taller green bars denote better performances.

The results show that Self-Consistency effectively minimizes the frequency of errors while correcting a significant number of wrong answers. In contrast, while Multi-Persona and AgentVerse sometimes achieve comparably tall green bars, these methods often fail to preserve correct answers. This suggests that MAD methods can be overly aggressive, lacking the ability to reliably identify incorrect answers. Consequently, MAD methods generally exhibit taller red bars compared to CoT or Self-Consistency.

| CCC | CCL | CGG | CLL | GCC | GGG | GGL | GLC | GLL | LLL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSM8k | 87.80 | 90.28 | 94.40 | 90.49 | 91.60 | 94.80 | 95.00 | 94.34 | 94.40 | 84.00 |

| HumanEval | 64.02 | 65.85 | 74.39 | 64.58 | 72.56 | 68.29 | 77.44 | 77.44 | 76.83 | 69.51 |

| MMLU | 55.13 | 67.20 | 70.02 | 70.00 | 67.40 | 75.00 | 79.00 | 71.92 | 88.20 | 84.20 |

Finally, we explore whether different foundation models can serve as the key factor to a better performance. We enumerate different combinations of GPT-4o-mini, Llama3.1-70b, Claude-haiku

Limitations

In this part, we discuss the limitations of our evaluation design to mitigate concern about whether our evaluation can fairly compare MAD frameworks against other baselines. First, our evaluation of MAD configuration sensitivity is limited to the number of agents, the number of debating rounds, and the different foundation models incorporated. These configurations are paid extra attention during evaluation due to most MAD frameworks provide flexibility in adjusting them. Therefore these configurations are the prior candidates to be changed when the MAD framework is deployed. Due to the heavy expense involved in inferring with LLMs, we limit the scale of our ablation studies to control the total expense. However, in our evaluation, we didn’t observe obvious trends in performance concerning more agents or more debating rounds.

Another limitation in our evaluation is the prompt used to invoke LLM agents. We strictly followed the original prompt configuration of considered MAD frameworks with necessary modifications to make the MAD run in an expected way. While we didn’t extensively search for an optimal combination of MAD prompts, we made sure that all key ideas and components proposed in existing MAD frameworks were carefully implemented and observed in the debating procedure, e.g., the confidence level of agent in EoT and the expert-hiring stage in AgentVerse. Therefore, our implementation can be considered a qualitative reproduction of existing MAD frameworks.

Discussion

We obtain consistent observation with existing research

While the empirical results shown above are surprising that most MAD frameworks cannot even perform better than CoT, we want to clarify that our observation is not contradictory with previous outcomes in MAD research. Specifically, SoM, AgentVerse, and ChatEval were not compared against CoT on these widely used benchmarks. MP was evaluated against CoT only on a handcrafted dataset named Counter-Intuitive Arithmetic Reasoning (CIAR). EoT was compared to CoT on GSM8k only, in which EoT was shown to be slightly better than CoT. We observe the same result in our evaluation. Therefore, our empirical results are consistent with former observations.

Potential future directions

Although the previous part of this blog post mostly reflected a negative outcome of current MAD methods, we want to emphasize that this is by no means indicating that MAD is not worth further exploration. Instead, we would argue that the development of MAD methods is still in its early stages, with limited exploration of the deep-level mechanisms behind MAD frameworks. We list several possible future directions in the development of MAD frameworks.

First, most test cases in existing benchmarks only require a single knowledge point to be solved, which naturally makes MAD unnecessary. Under this circumstance, MAD degrades to an inefficient resampling method aggregating responses from agents via natural language communication. Such benchmarks cannot accurately reflect the complex reasoning capability of MAD. Besides, recently proposed MAD frameworks may be optimized to be effective on these benchmarks, which strictly limit the development of MAD methods.

What’s more, current MAD methods are not fine-grained enough. Agents debate based on their full responses to the given query. Consequently, agents overly assign weight to the final answer instead of the reasoning steps. When an agent receives different answers from another agent, it will establish its debating response mostly based on the fact that the other agent answers differently, instead of analyzing the gap between their reasoning and why they obtain different answers.

We also observe that directly adopting a pre-trained LLM for debating may be sub-optimal. As discussed above, LLM inherently has certain preferences for candidate answers, which may prohibit debaters from accurately selecting the answer fully based on its correctness. In other words, it may not be appropriate to directly deploy pre-trained LLMs in the MAD framework. In context learning or supervised fine-tuning could help pre-trained learn how to debate effectively.

Conclusion

In this blog, we review existing MAD frameworks, with a specific focus on the comparison between MAD frameworks and single-agent inference methods. With comprehensive evaluation, we conclude that current MAD frameworks do not consistently outperform baseline methods including Chain-of-Thought and Self-Consistency. Our ablation study showed that MAD cannot scale well with increased inference budget. However, we believe MAD frameworks still have the potential to take effect, given that combining multiple foundations models showed promising performance improvement. We also note that current MAD designs may have some drawbacks limiting the performance, which we list as future directions in our discussion.