Flaws of ImageNet, Computer Vision's Favorite Dataset

Since its release, ImageNet-1k has been a gold standard for evaluating model performance. It has served as the foundation of numerous other datasets and it has been widely used for pretraining.

As models have improved, issues related to label correctness have become increasingly apparent. In this blog post, we analyze the issues, including incorrect labels, overlapping or ambiguous class definitions, training-evaluation domain shifts, and image duplicates. The solutions for some problems are straightforward. For others, we hope to start a broader conversation about how to improve this influential dataset to better serve future research.

Disclaimer: By undertaking this work, we have no intention to diminish the significant contributions of ImageNet, whose value remains undeniable. It was, at the time of its publication, far ahead of all existing datasets. Given ImageNet-1k’s continued broad use, especially in model evaluation, fixing the issues may help the field move forward. With current tools, we believe it is possible to improve ImageNet-1k without huge manual effort.

Introduction to ImageNet-1k

Brief History

The concept of ImageNet

Introduced in 2012, ImageNet-1k

Problems

We were aware that ImageNet-1k had issues, which is common in real-world datasets. However, while analyzing model errors for another project, we were surprised by the size of the effects of the problems related to the ground truth. We decided to investigate them in greater detail. The initial goal looked simple: correct the labels to reduce noise — a task we assumed would be straightforward. However, upon further examination, we discovered that the issues were complex and far more deeply rooted.

The easy-to-solve issues, such as incorrect image labels, redundant classes, and duplicate images, can be addressed by relabeling, merging classes, and cleaning up duplicates. However, there are other issues, such as a distribution shift between the training and evaluation subsets, where we see no fully backward-compatible solution. The domain shift could even be seen as a feature rather than a bug since in real deployment, test and training data are never i.i.d. (independent and identically distributed). The inclusion of images depicting objects from multiple ImageNet classes, called multilabel images, poses another problem with no straightforward solution. Their removal is a possibility when ImageNet-1k is used for training. However, their prevalence, which we estimate to be in the 15 to 21% range in the validation set, probably rules out adopting this solution. Other modifications of the evaluation protocol might be preferable, e.g. considering any predicted label from the multilabel ground-truth set as correct. Referred to as ReaL accuracy

Known ImageNet-1k Issues

Prior studies identified and analyzed many ImageNet issues, but they each deal only with a specific concern and usually focus on the validation set. The topic that received the most attention is annotation errors, which distort the evaluation of model accuracy

Prior Work in Detail

Bringing the Errors Together

After downloading the available corrected labels from prior studies and analyzing them, we discovered that approximately 57.2% of the images in the validation set had been reviewed by multiple studies. Further examination revealed that only 33% of the entire validation set has identical labels across all the studies. This finding reminds us that error-correction processes are not error-free. We analyzed the images with consistent labels, and for nearly 94% of them, the original labels were correct. The remaining 6% consists of ambiguous and multilabel images, as well as images where annotators fully agreed on a label different from the original.

Results Evaluation Note

Bottom: Images checked by more than one paper where the annotators agreed and disagreed .

This analysis highlights significant inconsistencies in the labeling of reannotated images. The discrepancies between the studies arise from each following its own methodology, leading to varying interpretations of the class definitions and different approaches to resolving issues encountered during annotation.

Dataset Construction Issues

Let us first examine the two-step process used to construct ImageNet:

- Image collection. Images were scraped from the web and organized according to the WordNet hierarchy, which will be revisited later. Both automated and manual methods were involved: automated tools initially assigned labels based on metadata available (textual description, category) at the image source, often flickr.

- Annotation process. The preliminary labels were then reviewed by MTurk workers, who were only asked to confirm whether the object with the given label was present in the image. Notably, no alternative labels were suggested, such as other similar classes. The MTurkers were shown the target synset definition and a link to Wikipedia.

ImageNet-1k consists of three sets: a training set with over 1 million images, a validation set with 50,000 images, and a test set with 100,000 images. The training set is drawn from ImageNet. Images for the evaluation subsets were obtained through a process that tried to replicate the one used for the ImageNet. The new data were collected up to three years later than training data and then they were randomly split between the validation and test sets.

ImageNet links each image category to a WordNet noun synset. WordNet is a comprehensive lexical database of English. It organizes nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs into synonym sets, or synsets, each representing a unique concept (see the official website).

Each synset should consist of one or more terms referred to as “synonyms”, for example, “church, church building”. However, they are not synonyms in all cases. For example, consider the synset “diaper, nappy, napkin”. The first two terms are synonyms, the third one is not. Moreover, there are cases where the same term is in more than one synset, e.g. there are two synsets named “crane” — one defining a bird and the second a machine. In ImageNet-1k, they are separate classes. Think about the consequences for zero-shot classification with vision-language models (VLMs) like CLIP

We will demonstrate some issues related to dataset construction with a few examples.

The Cat Problem

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Looking at the “tiger cat” images above, you might think “This seems to be a really diverse dataset…”. Let us have a closer look. The “tiger cat” class is defined in WordNet as “a cat having a striped coat”, which aligns precisely with (a).

To understand the issue with (b), we must know that ImageNet-1k also includes a “tabby, tabby cat” class, defined as “a cat with a grey or tawny coat mottled with black”. In common usage, tabby cat refers broadly to any domestic cat with a striped, spotted, or swirled coat pattern, all of which must include an “M” marking on their forehead (which can be seen in this image). Most dictionaries agree that all tiger cats are tabbies, but not all tabby cats have the tiger pattern. However, even if we look at image (b) through the lens of WordNet definitions, it shows a grey cat, but its coat is not clearly visible. Moreover, the term “mottled coat” in the tabby cat definition can be somewhat confusing, as some dictionaries consider stripes to be a type of mottling. So, how do we determine which type of cat this is?

We find modern large language models (LLMs) to be more accurate when handling such questions, so we asked them whether these two definitions overlap:

– ChatGPT-4o

– Claude 3.5 Sonnet

– Microsoft Copilot

This raises the question: If WordNet definitions are not precise enough, what is the ultimate source for correct image labels? ChatGPT, Wikipedia, GBIF?

We are not wildlife experts, but we may say that either an oncilla, ocelot, or margay is in (c). While this might seem like harmless noise, common in such large datasets, these animals do appear more than once in the training set. In everyday language, “tiger cat” is more commonly used to refer to these wild cats than to striped domestic ones; however, these usages coexist simultaneously.

We have already mentioned the WordNet definition of the “tiger cat” synset; WordNet also contains a “tiger cat, Felis tigrina” synset, defined as “a medium-sized wildcat of Central America and South America having a dark-striped coat”. All three cat species we have mentioned as possible labels for (c) fit the definition. Consistently annotating “tiger cat” images given such confusing background information is difficult for experts, and probably impossible for MTurkers.

Obviously, (d) is a tiger, which has a class, “tiger, Panthera tigris”. Tigers make up a significant portion of the “tiger cat” class in both the training and validation sets. Distinguishing between a tabby and a tiger is not a challenging recognition task and yet the non-expert annotators made many mistakes. This highlights the need to think carefully about the expertise of and guidelines for the annotators.

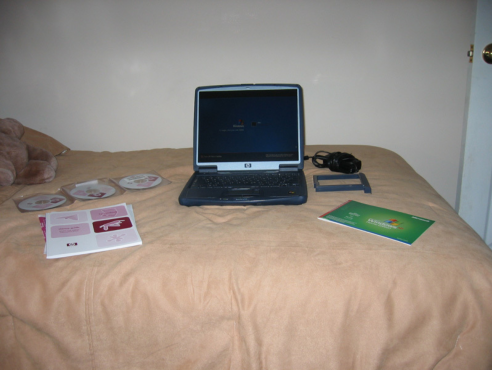

The Laptop Problem

"laptop, laptop computer"

"notebook, notebook computer"

Consider two synsets: “laptop, laptop computer” and “notebook, notebook computer”. Their respective WordNet definitions are “a portable computer small enough to use in your lap” and “a small compact portable computer”. In this case, the definitions overlap, with the former being a subset of the latter. We again asked modern LLMs about the difference between laptop and notebook:

– ChatGPT-4o

This raises a question whether there is any other solution besides merging these two classes into a single class with 2600 training images or changing the evaluation protocol so that laptop – notebook swaps are not penalized.

Exploring VLM Results

We expected the issues described above to have an impact on the results of Vision Language Models. To test the hypothesis, we selected a zero-shot open-source model, OpenCLIP (ViT-H-14-378), and examined its predictions on the training set for the classes discussed above. The confusion matrices below show the discrepancies between the original and predicted labels.

| Predicted Label (OpenCLIP) → | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Label ↓ | tabby, tabby cat | tiger cat | tiger, Panthera tigris | Other classes |

| tabby, tabby cat | 76.4% | 8.5% | 0% | 15.1% |

| tiger cat | 57.2% | 6.9% | 23.8% | 12.1% |

| tiger, Panthera tigris | 0.1% | 0% | 99.2% | 0.7% |

Note that the differences can be both due to OpenCLIP’s errors and wrong ground truth labels. Nearly a quarter of the images in “tiger cat” class are predicted to be tigers, which we trust to be an estimate of the percentage of tigers in the training data of the class. Only 6.9% of the images are predicted as “tiger cat”, highlighting the conceptual overlap with “tabby, tabby cat”.

| Predicted Label (OpenCLIP) → | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Original Label ↓ | laptop, laptop computer | notebook, notebook computer | Other classes |

| laptop, laptop computer | 35.8% | 44.6% | 19.6% |

| notebook, notebook computer | 17.2% | 65.8% | 17% |

Approximately 80% of the images in these classes were predicted as either a notebook or a laptop, with an error not far from random guessing. The remaining 20% were assigned to other labels. This will be discussed in the section on multilabels.

Key Takeaways

The examples demonstrate that the incorrect labels are not caused just by random noise, but they are also a consequence of the dataset’s construction process. WordNet is not error-free and fully consistent; the issues propagate to ImageNet. Also, some meanings shift over time, which is a problem in the era of VLMs. Perhaps WordNet and ImageNet should co-evolve.

Relying solely on MTurkers and using Wikipedia (a source that may be continuously edited by non-experts and may lack precise definitions) not only led to the inclusion of noisy labels but also sometimes distorted the very concepts that the classes were intended to represent. For example, the “sunglasses, dark glasses, shades” and “sunglass” classes represent the same object — sunglasses. While this is accurate for the “sunglasses”, the “sunglass” class is defined in WordNet as “a convex lens that focuses the rays of the sun; used to start a fire”. This definition was lost during the dataset construction process, resulting in two classes representing the same concept.

Distribution Shift Between Training and Validation Sets

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

As mentioned earlier, for ImageNet-1k, additional images were collected using the same strategy as the original ImageNet. However, even with the same process, issues arose.

For example, in the training set, the “canoe” class mainly consists of images of canoes, but it also includes many images of kayaks and other types of boats. In contrast, the “canoe” class in the validation set only contains images of kayaks, with no canoes at all.

To clarify, the difference is not only in the boat shapes, with a kayak being flatter, but also in how they are paddled. A canoe is typically paddled in a kneeling position (though seated paddling is common) with a short single-bladed paddle, while a kayak is paddled from a seated position with a long double-bladed paddle. Interestingly, “paddle, boat paddle” is a separate class in ImageNet-1k.

The “planetarium” class exhibits another issue. In the validation set, 68% of the images (34 out of 50) feature the same planetarium in Buenos Aires. The building appears many times in the training set too, but the range of planetaria is much broader. Perhaps it is a beautiful location, and the authors enjoyed featuring it, but it is not i.i.d.

Here, the solution is fairly straightforward - collecting a more representative set of images. Nevertheless, this breaks backward compatibility, rendering old and new results incomparable.

Images Requiring Multiple Labels

We illustrate the problem of multilabel images with an extreme example. What do you think is the correct label for the following image?

The following objects in the image have a class in ImageNet-1k:

- Space bar

- Monitor

- Screen

- Laptop

- Desktop computer

- Desk

- Website

- Printer

One could argue that in the presence of multiple objects from distinct classes, the dominant should be labeled, but here and elsewhere, it is not clear what the dominant object is.

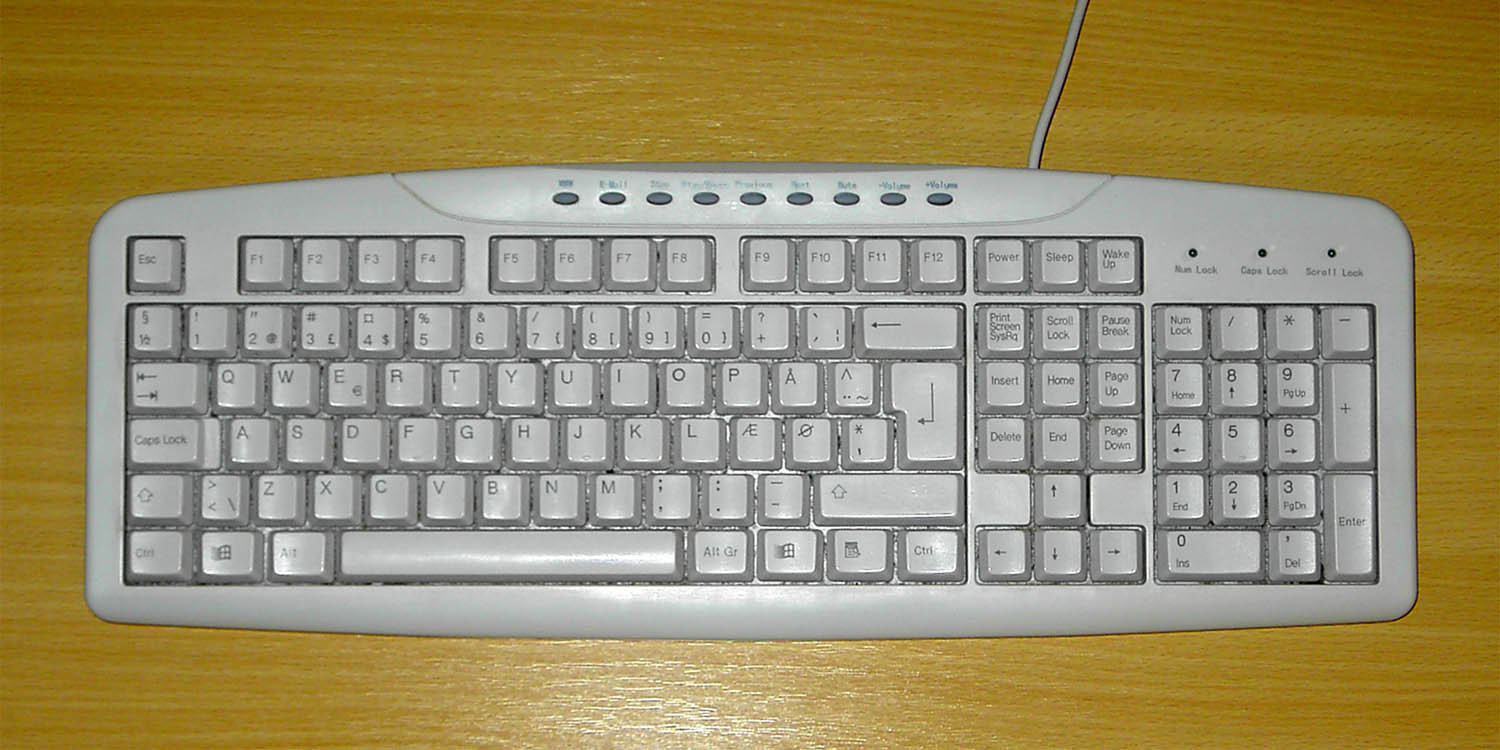

As with the “canoe” and “paddle” classes in the section about domain shift, some objects naturally appear together in photos. In everyday usage, desktop computers are accompanied by a computer keyboard and a monitor (all of which are ImageNet-1k classes). The difference between a monitor and a screen, another pair of questionable ImageNet-1k classes, is an issue in its own right. Additionally, desktop computers are generally placed on desks (also a class), so these two objects often appear together in images. Many cases of multilabel image issues stemming from frequently co-occurring classes exist.

The issue runs deeper, and the authors’ claim that there is no overlap and no parent-child relationship between classes appears to be incorrect. Consider the example of a “spacebar” and a “computer keyboard”. The “space bar” may not always be part of a “computer keyboard”, but most “keyboards” do have a “space bar”.

Let us look at another example.

"car wheel"

"sports car, sport car"

A wheel can exist without a car, but a car — except for some rare cases, say in a scrapyard — cannot exist without a wheel. When an image contains both, and many do, it is unclear which label should take priority. Even if MTurkers were familiar with all 1000 ImageNet-1k classes, assigning a single accurate label would still be challenging.

As mentioned in the section about dataset construction, MTurkers were asked to determine whether an image contains an object that matches a given definition. Such a process of annotation may not be inherently problematic. However, when paired with the problematic class selection, our next topic, it is.

ILSVRC Class Selection

The ImageNet-1k classes were chosen as a subset of the larger ImageNet dataset. One reason the dataset is so widely used is that it is perceived to reflect the diversity of the real world. Yet, the class distribution is skewed. Does having more than 10% of the dataset represent dog breeds truly capture the human experience as a whole, or is it more reflective of dog owners’ perspective? Similarly, is having a separate class for “iPod” — rather than a broader category like “music player” — a durable representation of the world?

Taxonomy of class selection problems

We categorize the problems with class selection as follows:

Class Is a Subset or a Special Case of Another Class

- “Indian elephant, Elephas maximus” & “African elephant, Loxodonta africana” are also “tusker”

- “bathtub, bathing tub, bath, tub” is also a “tub, vat”

"bathtub, bathing tub, bath, tub”

"tub, vat”

Class Is a Part of Another Class Object

- “space bar” is a part of “computer keyboard, keypad”

- “car wheel” is a part of any vehicle class (“racer, race car, racing car”, “sports car, sport car”, “minivan”, etc.)

"space bar"

"computer keyboard, keypad"

Near Synonyms as Understood by Non-experts

- “laptop, laptop computer” & “notebook, notebook computer”

- “sunglasses, dark glasses, shades” & “sunglass”

"sunglasses, dark glasses, shades"

"sunglass"

Mostly Occur Together

- “sea anemone” & “anemone fish”

- “microphone, mike” & “stage”

"sea anemone"

"anemone fish"

We ran hierarchical clustering on the confusion matrix of EfficientNet-L2

The full list of problematic categories is here. OpenCLIP accuracies for both problematic and non-problematic groups of classes are given in Table 3.

| Dataset | Overall Accuracy | Problematic Classes Accuracy | Non-problematic Classes Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation | 84.61% | 73.47% | 86.59% |

| Training | 86.11% | 75.44% | 88.02% |

The classes from problematic groups have a significantly lower OpenCLIP accuracy.

Addressing Duplicates

"lynx, ..." ×

"timber wolf, ..." ✓

"dingo, ..." ×

"white wolf, ..." ×

"red wolf, ..." ×

"coyote, ..." ×

Of all prior studies, When Does Dough Become a Bagel?

The “planetarium” class mentioned earlier is a great example. It contains many near-duplicate images, as was noted in the section focused on distribution shift. Specifically, 68% of the validation images feature the same building in Buenos Aires. This observation naturally led us to investigate the issue of image duplicates more comprehensively.

Our analysis focuses on three types of duplicate sets:

- Cross-duplicates between the validation and training sets (identified in earlier research).

- Duplicates within the validation set (new findings).

- Duplicates within the training set (new findings).

The search began with the duplicate candidate detection process. We then categorized duplicates into 2 groups: exact duplicates and near duplicates, and the results are surprising…

Candidate Detection Details

- Each image $I_i$ has an embedding, $\mathbf{e}(I_i)$, in the feature space.

- The K-NN algorithm finds the 5 closest neighbors for each image.

- $d(\mathbf{e}(I_i), \mathbf{e}(I_j))$ represents the cosine distance between the embeddings of two images.

- $\tau$ is a predefined confidence threshold chosen high enough to ensure that no true positives are lost.

Exact Duplicate Search: Pixel-Level Comparisons

Key Findings

- In the validation set, 29 duplicate pairs were found. Each image in a pair belonged to a different ImageNet class.

- In the training set, 5,836 distinct images fall into duplicate groups, with 2 to 4 images per group. Most of these groups (with 5,782 distinct images) contained images assigned to different classes. This highlights that cross-class deduplication was not performed during the dataset creation.

- For the cross-validation-training search, we confirm that 797 images in the validation set had duplicates in the training set. All these duplicate groups also consisted of images assigned to different ImageNet classes which is in agreement with previous studies

.

Bonus

-

In the test set, 89 duplicate pairs were found.

Since labels for the test set are not publicly available, we cannot determine whether the images in each pair have the same label or not. However, given that the test and validation sets were created simultaneously by splitting the collected evaluation data, we can infer that the situation is likely similar to the validation set. This suggests that each image in a pair belongs to a different class, which sets a lower bound on accuracy on the test set.

After finding exact duplicates, we removed them and recalculated the accuracies of two models: OpenCLIP and an ImageNet-pretrained CNN EfficientNetV2. We conducted three experiments. First, we removed all duplicate pairs in the validation set (Table 4, x Val). Next, we removed all duplicate images in the validation set that were also present in the training set (Table 4, x Cross). Finally, we combined these two methods to remove all exact duplicates (Table 4, x Val+Cross). In summary, our approach led to a 0.7% accuracy increase for the zero-shot model and a 1% accuracy increase for the pretrained CNN. We remind the reader that all exact duplicates have different labels and their erroneous classification is very likely; the improvement is thus expected.

| Model | Standard | × Val | × Cross | × Val+Cross |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenCLIP | 84.61 | 84.67 | 85.27 | 85.32 |

| EfficientNetV2 | 85.56 | 85.62 | 86.51 | 86.57 |

Near Duplicate Detection Method

The initial automatic search for duplicates was followed by a careful manual review of duplicate candidate images. After the review, each image was classified into one of the following near-duplicate groups.

Image Augmentations: images that result from various transformations applied to the original image, such as cropping, resizing, blurring, adding text, rotating, mirroring, or changing colors. An example is shown below.

(a) "computer mouse" from the validation set

(b) "mousetrap" from the training set

(c) pixels that differ in (a) and (b)

Similar View: images of the same object taken from slightly different angles at different times. An example is depicted below.

"dam, dike, dyke" from the validation set

"dam, dike, dyke" from the training set

Key Findings

- In the validation set, 26 near-duplicate groups were found, involving 69 images in total. All duplicates in a group had consistent labels.

- For the cross validation-training search, we discovered that 269 images from the validation set matched 400 training images.

We continued evaluating models with near duplicates removed. First, we removed all near duplicate groups in the validation set (Table 5, x Val). Next, we removed validation images that appeared in the training set (Table 5, x Cross), and then we removed both (Table 5, x Val + Cross). Lastly, we removed all exact duplicates and near duplicates from the validation set (Table 5, x All). As shown in Table 5, removing near duplicates had minimal impact on accuracy, as these images were mostly consistently assigned the same label within each duplicate group.

| Model | Standard | × Val | × Cross | × Val+Cross | × All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenCLIP | 84.61 | 84.60 | 84.63 | 84.62 | 85.32 |

| EfficientNetV2 | 85.56 | 85.54 | 85.59 | 85.59 | 86.59 |

Prompting Vision-Language Models

CLIP zero-shot classification is based on the distance of the image embeddings to the text embeddings representing each class. A natural approach is to create class embeddings based on the WordNet synset names. However, there are problems, such as overlapping synsets or WordNet synsets whose meanings evolve over time. For example, the term maillot appears in both “maillot” and “maillot, tank suit”. The first synset definition is “tights for dancers or gymnasts”, while the second one is “a woman’s one-piece bathing suit”.

Class Text Prompt Modifications: An Empirical Study

To illustrate the impact of class names in zero-shot recognition, we developed a new set of “modified” class names, building on OpenAI’s version of the ImageNet-1k class names. In the notebook, the authors suggest further work with class names is necessary. In the experiments, we decided to use OpenCLIP, an open-source implementation that outperforms the original CLIP model.

Table 6 shows recognition accuracy for the five classes with the most significant gain when using OpenAI class names vs. the original ImageNet names. The changes primarily address CLIP’s need for a broader context. For instance, in ImageNet, “sorrel” refers to a horse coloring, while in common usage, we’re used to hearing it refer to a plant. This can be a problem for VLMs due to the lack of context, which in turn the new class name “common sorrel horse” provides.

| ImageNet Class Name (WordNet) | OpenAI Class Name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| "sorrel" | 0% | 98% | "common sorrel horse" |

| "bluetick" | 0% | 78% | "Bluetick Coonhound" |

| "redbone" | 0% | 78% | "Redbone Coonhound" |

| "rock beauty, Holocanthus tricolor" | 22% | 96% | "rock beauty fish" |

| "notebook, notebook computer" | 16% | 66% | "notebook computer" |

Table 7 demonstrates the improvement of our modifications w.r.t. OpenAI’s class names. Notably, renaming “coffee maker” to “coffeepot” not only increased accuracy within this class but also positively impacted the class “espresso machine”, where no changes were made.

| OpenAI Class Name | "Modified" Class Name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| "canoe" | 48% | 100% | "kayak" |

| "vespa" | 42% | 82% | "motor scooter" |

| "coffeemaker" | 48% | 84% | "coffeepot" |

| "sailboat" | 76% | 100% | "yawl (boat)" |

| "espresso machine" | 50% | 72% | "espresso machine" |

Our modifications were found by trial and error, which suggests that there is a large space for possible improvement in VLM text prompting.

Fixing ImageNet Labels: A Case Study

Do you know the precise difference between a weasel, mink, polecat, black-footed ferret, domestic ferret, otter, badger, tayra, and marten? Most likely not. We use these animal species to illustrate the complexity of image labeling in ImageNet-1k.

With the help of an expert, images from the following 4 classes are considered for re-annotation:

- "weasel"

- "mink"

- "polecat, fitch, foulmart, foumart, Mustela putorius"

- "black-footed ferret, ferret, Mustela nigripes"

"weasel"

"mink"

"polecat, fitch, foulmart, foumart, Mustela putorius"

"black-footed ferret, ferret, Mustela nigripes"

These classes have a high percentage of incorrect ground truth labels, both in the training and validation sets. Most of the errors are caused by confusion between the four classes but the sets also contain images depicting animals from other ImageNet-1k classes, such as otter or badger, as well as images from classes not in ImageNet-1k, e.g. vole or tayra. But that is not the sole issue.

The Weasel Problem

Let us look at the “weasel” class definitions:

- WordNet: small carnivorous mammal with short legs and elongated body and neck.

- Wikipedia: the English word weasel was originally applied to one species of the genus, the European form of the least weasel (Mustela nivalis). This usage is retained in British English, where the name is also extended to cover several other small species of the genus. However, in technical discourse and in American usage, the term weasel can refer to any member of the genus, the genus as a whole, and even to members of the related genus Neogale.

- Webster: any of various small slender active carnivorous mammals (genus Mustela of the family Mustelidae, the weasel family) that can prey on animals (such as rabbits) larger than themselves, are mostly brown with white or yellowish underparts, and in northern forms turn white in winter.

The definition of the “weasel” synset in WordNet is broad - it potentially encompasses all the other mentioned classes. Moreover, the interpretation of the term weasel varies, between UK and US English, further complicating its consistent application. In US English, the term weasel often refers to the whole Mustelidae, also called ‘the weasel family’. All of the following - weasel, mink, European polecat, and black-footed ferret - belong to the weasel family, as understood by US English. One possible solution is to define the “weasel” class more precisely as the subgenus Mustela, which contains the ‘least weasel’ and other very similar species, which would lead only to the removal of a few images.

The Ferret Problem

Another complication arises with the “black-footed ferret” and “polecat” classes:

- WordNet synset name: “black-footed ferret, ferret, Mustela nigripes”

- ferret, Webster: ‘a domesticated usually albino, brownish, or silver-gray animal (Mustela furo synonym Mustela putorius furo) that is descended from the European polecat’.

- black-footed ferret, Wikipedia: ‘the black-footed ferret is roughly the size of a mink and is similar in appearance to the European polecat and the Asian steppe polecat’.

The synset “black-footed ferret, ferret, Mustela nigripes” includes both the term ‘black-footed ferret’ and ‘ferret’. The latter refers to a domesticated variety of the European polecat. Consequently, the term ‘ferret’ is ambiguous; it may be understood both as a synonym for the black-footed ferret or as the domesticated polecat. Additionally, the domestic ferret and European polecat are nearly indistinguishable to non-specialists; even experts may face difficulties because these species can interbreed. There is also a potential for contextual bias in labeling, as ferrets are commonly found in domestic environments or in the presence of humans.

European polecat

domestic ferret

To make matters worse, in the validation set for the class “black-footed ferret”, only one image depicts this species! A solution to this problem thus requires not only removal, or transfer to the correct class, of the incorrectly labeled images, but also collection of new data.

The term polecat presents a similar ambiguity w.r.t. the term ferret, as it is currently included in two synsets. One synset refers to skunk (family Mephitidae), while the other to Mustela putorius, the European polecat. These are in line with the definitions of the word polecat here.

European polecat

skunk

To solve the ‘ferret’ issues, redefinition of classes might be needed, e.g.:

- Introduction of a distinct class for ferret, specifically denoting the domesticated form of the European polecat.

- Reclassification of the term polecat so that it no longer appears in the synset for skunk; instead, this term should be used to represent a broader category encompassing both the European polecat and American polecat (also referred to as the black-footed ferret), as well as other species, such as the marbled, steppe, and striped polecats.

- Create a class that encompasses both polecats and ferrets.

Results of Relabeling

After relabeling the weasel family classes, we found that only the “mink” class had more than 50% of the original labels correct. The percentage of the correctly labeled images in ImageNet-1k was:

| Class Name | Percentage Correctly Labeled |

|---|---|

| Weasel | 44% |

| Mink | 68% |

| Polecat | 32% |

| Black-footed ferret | 2% |

The misclassified images either show an animal from the aforementioned classes or from a different ImageNet class (such as otter or badger). There are also images of animals outside of ImageNet-1k classes, while some images are ambiguous, see Figure 22.

Images of animals that do not belong to any ImageNet class are assigned to the ‘non-ImageNet’ label in the graph shown in Figure 23. This category includes animals such as vole, tayra, marten, and Chinese ferret-badger. Although ‘domestic ferret’ is also a non-ImageNet label, it is shown separately because of its large representation in the sets.

characteristic features obscured

too far for identification

The ‘ambiguous’ label is used for images that are blurry, have the characteristic features of the species obscured, show the species from too great a distance, or have other flaws that prevent unequivocal identification of the species.

Let us take a closer look at the four examined classes.

The weasel class contains a wide variety of misclassified images. This includes minks (6%), polecats (16%), domestic ferrets (10%), otters (6%), and badgers (6%). The high rate of misclassification may be due to the unclear definition of this class, as all of these species belong to the weasel family discussed earlier.

The “mink” class is predominantly correctly labeled but a substantial portion (30%) of images is ambiguous; meaning they are low quality or the subject is obscured. These images should preferably be removed or assigned multiple possible labels (single object but ambiguous).

The “polecat” class has a significant percentage (40%) of images depicting domestic ferrets. That is not surprising as distinguishing between polecats and domestic ferrets is particularly challenging.

Finally, the “black-footed ferret” class contains only one image of this species, while the majority (80%) of the images depict domestic ferrets.

Luccioni and Rolnick (2022)

Conclusions

The blogpost deals with the problems of the ImageNet-1k dataset, both pertaining to image data selection and the ground truth labels. Most of the issues have been known to exist, like the presence of: incorrectly labeled images, multilabel images with no obvious correct label, overlapping class definitions, and the presence of intra-set duplicates and near-duplicate instances.

The analysis here is more in-depth provides new quantitative information about the phenomena and presents new findings, e.g. about the distribution shift between the training and validation sets, intra-set duplicates, and near-duplicate instances within both training and validation sets. We also introduce new, improved class names for zero-shot recognition with VLMs, as well as a refined taxonomy of problematic classes—such as hierarchical and duplicate classes—while introducing new ones, e.g. “part-of” and co-occurrence relationships.

For many problems, we provide exemplars, such as the expert-led case study of closely related weasel family species, which highlights the complexity of fine-grained classification. The training-validation domain shift is demonstrated on the canoe & kayak and planetaria classes. We discuss the causes of the problems, some rooted in ImageNet’s dataset collection process, particularly the reliance on untrained Mechanical Turk workers, and some originating from ambiguous WordNet definitions, exemplified by the tiger cat class.

At a technical level, we consolidate and publish prior ImageNet-1k label error corrections, resulting in the “clean validation set” with consistent image labels from previous studies, and provide the improved VLM zero-shot prompts for all ImageNet classes.

Outlook

The blog mainly focuses on a precise description of the issues and their scale, i.e., what fraction of the image-label pairs it affects. We hope that one of the outcomes of publishing this analysis will be a broader exchange of ideas on what is and what is not worth fixing. Every solution will involve trade-offs, at least between correctness and backward compatibility. The wide use of ImageNet-1k makes it difficult to assess the full impact of any change; possibly we are heading towards multiple evaluation protocols and ground-truth versions.

The activity opened many questions. First and foremost: “Is this worth it?” and “Will the community benefit from (much) more accurate ImageNet-1k re-labeling and class definitions?”. For the validation set, which is used for performance evaluation of a wide range of models, the answer seems a clear “yes”. For the training set, we see benefits too. For instance, it seems that learning a fine-grained model from very noisy data is very challenging. The answers to the questions above depend on the effort needed to re-label the images and to clean the class definitions. Our experience is that current tools, both state-of-the-art classifiers and zero-shot VLM models, reduce the need for manual effort significantly.

The effort to find precise, unambiguous definitions of the ImageNet-1k classes lead us to the use of VLMs and LLMs. The LLM responses were accurate and informative if prompted properly, even warning about common causes of confusion. Our experience suggests that LLMs are very suitable for both annotator training and decision support.

We hired an expert annotator in order to obtain precise annotation of the weasel-like animal classes analyzed in the case study. Expert annotators help identify subtle nuances and complexities within the dataset that might be easily overlooked by non-specialists. On the other hand, their understanding of certain terms might not coincide with common usage. We might need parameterizable VLM models, e.g., for professional and technical use as well as for the vernacular. Prior work

In many areas of computer vision, models reached accuracy comparable to the so-called ground truth, losing the compass pointing to better performance. As we have seen, improving ground truth quality is not a simple task of checking and re-checking, but touches on some core issues of both vision and language modeling. This blog is a small step towards resetting the compass for ImageNet-1k.