A primer on analytical learning dynamics of nonlinear neural networks

The learning dynamics of neural networks—in particular, how parameters change over time during training—describe how data, architecture, and algorithm interact in time to produce a trained neural network model. Characterizing these dynamics, in general, remains an open problem in machine learning, but, handily, restricting the setting allows careful empirical studies and even analytical results. In this blog post, we review approaches to analyzing the learning dynamics of nonlinear neural networks, focusing on a particular setting known as teacher-student that permits an explicit analytical expression for the generalization error of a nonlinear neural network trained with online gradient descent. We provide an accessible mathematical formulation of this analysis and a JAX codebase to implement simulation of the analytical system of ordinary differential equations alongside neural network training in this setting. We conclude with a discussion of how this analytical paradigm has been used to investigate generalization in neural networks and beyond.

Background

The dynamics of learning in artificial neural networks capture how the parameters of a network change over time during training as a function of the data, architecture, and training algorithm. The internal representations and external behaviors of the network evolve during training as a consequence of these dynamics. In neural networks with at least one hidden layer, these dynamics are nonlinear even when the activation function is linear

Empirical studies of learning dynamics

Empirical work uses simulations of training dynamics to visualize and characterize the geometry of neural network loss landscapes and the trajectories networks take during optimization. Early work by Choromanska et al.

Theoretical analyses of learning dynamics

Theoretical approaches to understanding neural network learning dynamics use mathematical tools to describe how network parameters evolve during training. These analyses have revealed two distinct training regimes. The first regime, known as lazy training

The second regime, termed feature learning

Statistical physics for learning dynamics

Statistical physics offers tools for characterizing macroscopic behavior emerging from collections of microscopic particles

Our focus: The teacher-student setting

The teacher-student framework, introduced by Gardner

Much recent work builds on these classical analyses to expand the frontier of solvable training regimes, and these techniques have also found applications beyond generalization error dynamics. We detail both directions in the final section of this blog post. First, we provide a pedagogical introduction to the classicial analytical results, focusing on the derivation of Saad & Solla

Methods

In this section, we introduce the teacher-student setup of Saad & Solla

The teacher-student setup

In the teacher-student setting of Saad & Solla

The teacher, including that of Saad & Solla

where \(f^{*}( \cdot , W^{*})\) is the mapping defining the teacher with parameters \(W^{*}\) of dimension to be defined, \(\xi^{u} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\), and \(\sigma \in \mathbb{R}\) scales the output noise.

The student network is generally defined as

\[\begin{equation} \hat{y}_{s}^{u} = f(x_{s}^{u}, W), \end{equation}\]where \(f( \cdot , W)\) is the mapping defining the student, and \(W\) are the parameters of the student of dimension to be defined. In teacher-student, \(f\) and \(f^{*}\) usually share the same parameterizaton to enable finegrained comparison between the learning of the student and the teacher defining the task. Commonly, they are both neural networks and the parameters \(W\) and \(W^{*}\) are the weights of the networks. In Saad & Solla

To train the student network, Saad & Solla

where samples to fill a batch consist of $(x_{s}, y_{s})^{u}$ pairs with $i = 1, \ldots, B$, $x_{s}^{u} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)$ of dimension $N$, and the target $y_{s}^{u}$ is generated by feeding $x_{s}^{u}$ to the teacher network. The weights of the student network are updated using gradient descent as

\[\begin{equation} W^{u+1} = W^{u} - \eta_{w} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}^{u}}{\partial W}~, \end{equation}\]where $\eta_{W}$ is the learning rate for parameters \(W\). This procedure can be shown to converge to near-zero training error (up to irreducible error due to noise ) in the limit of infinite data and infinitesmal learning rate if the student is sufficiently parameterized with respect to the teacher

Gradient flow dynamics: Learning with infinitesimal step size

One way to analyze learning dynamics of neural networks like that denoted in (4) is treat the optimization process as a dynamical system where the gradient descent updates effectively evolve through continuous time as the parameters of a dynamical system. This transformation is commonly known as the gradient flow limit

where \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle_{x,y}\) is physics notation for the expectation taken over the distribution of the data. In the gradient flow limit, the generalization error at each step can be written as

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{E}(W^u) = \frac{1}{2} \left\langle \left( \hat{y}^u - y \right)^{2} \right\rangle_{x,y}~. \end{equation}\]One way to think about the limit defined by (5) is by considering that as the learning rate gets smaller, the amount of data observed by the network at a fixed timescale increases, becoming virtually infinite when the learning rate is zero. This converts the finite average over data in the loss function in (3) to an expectation over the data as in (6).

The nonlinear gradient flow dynamics of teacher-student are solvable

It is possible to solve the system of ordinary differential equations in (5) for several classes of deep linear networks

In the next sections, we will rederive the dynamical equations for two paradigmatic cases of the teacher-student setting, the classical case of Saad and Solla

Rederivations

In this section, we present a pedagogical tour of the analytical framework of to characterize the gradient descent learning dynamics of the student network in terms of its order parameters, resolving some inconsistencies in the original derivations

Solvable learning dynamics for the soft committee machine

To solve the system of ordinary differential equations in (5), we need to assume a specific form for the teacher and student networks and convert the dynamical equation that describes gradient descent to the corresponding order parameters equations. In Saad and Solla’s work

where $g( \cdot )$ is the activation function, \(m\) and \(k\) index the perceptrons in the teacher and student (rows of \(W^*, W \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times N}\)), and $M$ and $K$ are the number of neurons in the teacher and student networks, respectively. Saad and Solla

To train the student, we minimize the mean squared error between the teacher and student outputs:

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{L^{u}} = & \frac{1}{2B} \sum_{i=1}^{B} \left( y_{s}^{u} - \hat{y}_{s}^{u} \right)^{2} \\ = & \frac{1}{2B} \sum_{s=1}^{B} \left[ \sum_{m=1}^ {M} g\left( \frac{W^{*}_{m}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) + \sigma \xi^{u} -\sum_{k=1}^{K} g\left( \frac{W_ {k}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \right]^{2} \end{align}\]We then perform gradient descent to update the student’s weights:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial W_{i}} = & \frac{1}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \left[\sum_{m=1}^ {M} g\left( \frac{W^{*}_{m}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) + \sigma \xi ^{u} -\sum_{k=1}^{K} g\left( \frac{W _{k}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \right] \cdot \left( -g'\left( \frac{W_{i}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \\ = & - \frac{1}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \frac{W_{i}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}}~. \end{align}\]with \(\Delta_{s}^{u} = \sum_{m=1}^{M} g\left( \frac{W^{*}_{m}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) + \sigma \xi^{u} - \sum_{k=1}^{K} g\left( \frac{W_{k}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right)\). Hence, the gradient descent update equations for the student network are

\[\begin{equation} W_{i}^{u+1} = W_{i}^{u} + \frac{\eta_{w}}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \frac{W_{i}x_ {s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}}~. \end{equation}\]From this expression, we could take the gradient flow limit as in (5). However, the expectation over the data distribution induced in the right hand side does not have a closed form solution in this case. Instead, we can write the update equation in terms of order parameters, which fully define the state of the system, and for which this expectation has a solution. We emphasize that the order parameters are a design choice to make analytical results tractable, and the choice of order parameters is not always obvious in any given problem. Saad & Solla

Instead of describing the learning using the gradient descent updates for the weights, we can describe it in terms of the order parameters in (14). To do this, we can simply multiply the gradient updates equation by \((W^{*}_{n})^{T}/N\) to obtain $R$ updates and by \((W_{j}^{u+1})^{T}/N\) to obtain $Q$ updates. Starting with the $R$ updates, we have

\[\begin{align} \frac{W_{i}^{u+1}(W_{n}^{*})^{T}}{N} & = \frac{W_{i}^{u}(W_{n}^{*})^{T}}{N} + \frac{\eta_{w}}{NB}\sum_{s= 1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^ {u} \cdot g'\left( \frac{W_{i}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u} (W_{n}^{*})^{T}}{\sqrt{N }}~, \\ R_{in}^{u+1} & = R_{in}^{u} + \frac{\eta_{w} \mathrm{d}t}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^ {u} \cdot g'\left( \frac{W_{i}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u} (W_{n}^{*})^{T}}{\sqrt{N}}~. \end{align}\]From this equation, we define $\mathrm{d}t=1/N$, and by moving $R_{in}^{u}$ to the left hand side, dividing by $\mathrm{d}t$, and taking the thermodynamic limit $N \rightarrow \infty$ corresponding to large input dimension, we obtain the time derivative of $R_{in}$ as

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\mathrm{d} R_{in}}{\mathrm{d} t} = \eta_{w} \left< \Delta_{s}^{u} g'(\lambda_{i}^{u}) \rho_{n}^{u} \right> \end{equation}\]where we define the local fields

\[\begin{equation} \lambda_{i}^{u} = \frac{W_{i}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \hspace{0.3cm} \text{and} \hspace{0.3cm} \rho_{n}^{u} = \frac{(W_ {n}^{*})^{T}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}}. \end{equation}\]The equation for $\frac{\mathrm{d}R_{in}}{\mathrm{d}t}$ is now in a convenient form, where the local fields are simply a Gaussian scalar since $x \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)$, and so the expectation because an integral over Gaussian distribution with covariances defined by the order parameters. Before solving this expectation, let’s derive the same equation for the order parameters $Q$ (slightly trickier). We go back to the gradient descent update equation for the weights, and multiply by $(W_{j}^{u+1})^{T}/N$ giving

\[\begin{align} \frac{W_{i}^{u+1}(W_{j}^{u+1})^{T}}{N} & = \frac{W_{i}^{u}(W_{j}^{u+1})^{T}}{N} + \frac{\eta_{w}}{NB}\sum _{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \lambda_{i}^ {u} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}}(W_{j}^{u+1})^{T}, \\ Q^{u+1}_{ij} & = \frac{W_{i}^{u}}{N}\left( W_{j}^{u} + \frac{\eta_{w}}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left ( \frac{W_{j}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right)^{T} \\ & + \frac{\eta_{w}}{NB}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \lambda_{i}^ {u} \right) \cdot \frac{ x_{s}^{u}} {\sqrt{N}} \left( W_{j}^{u} + \frac{\eta_{w}}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left ( \frac{W_{j}x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right) \cdot \frac{x_{s}^{u}}{\sqrt{N}} \right)^{T}, \\ Q^{u+1}_{ij} & = Q^{u}_{ij} + \frac{\eta_{w}dt}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \lambda_{j }^ {u} \right) \lambda_{i}^{u} + \frac{\eta_{w}dt}{B}\sum_{s=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \cdot g'\left( \lambda_{i}^{u } \right) \lambda_{j}^{u} \\ & + \frac{\eta_{w}^{2}dt}{B^{2}}\sum_{s=1}^{B}\sum_{s'=1}^{B} \Delta_{s}^{u} \Delta_{s'}^{u}g'\left( \lambda_{i}^{u} \right)g'\left( \lambda_{j}^{u} \right) \frac{x_{s}^{u}(x_{s}^{u})^{T}}{N}. \end{align}\]Now dividing by $\math{d}t$ and taking the limit $N \rightarrow \infty$, (hence $\mathrm{d}t \rightarrow 0$), $\frac{x_{s }^{u}(x_{s} ^{y})^{T}}{N} \rightarrow 1 $ by the central limit theorem, and expectations over \(s\) and \(s'\) are $0$ as they are independent samples, we obtain the time derivative of $Q_{ij}$ as

\[\begin{equation} \frac{\mathrm{d}Q_{ij}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \eta_{w} \left< \Delta_{s}^{u} g'(\lambda_{j}^{u}) \lambda_{i}^{u} \right> + \eta_{W } \left<\Delta_{s}^{u} g'(\lambda_{i}^{u}) \lambda_{j}^{u} \right> + \eta_{w}^{2} \left< (\Delta_{s}^{u})^{2} g'(\lambda_{i}^{u}) g'(\lambda_{j}^{u}) \right>. \end{equation}\]Finally, having the order parameters, we can write the generalization error from (6), the expected mean squared error between teacher and student over the entire data distribution, as

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{E} = & \frac{1}{2} \left< \left( \hat{y} - y \right)^{2} \right> \\ = & \frac{1}{2} \sum_ {i=1}^{K} \sum_{j=1}^{K} \left< g(\lambda_{i}^{u}) g(\lambda_{j}^{u}) \right> - \sum_{m=1}^{M} \sum_{i=1}^{K} \left< g(\rho_{m}^{u}) g(\lambda_{i}^{u}) \right> + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{m=1}^{M} \sum_{n=1}^{M} \left< g(\rho_{m}^{u}) g(\rho_ {n}^{u}) \right> + \frac{\sigma^{2}}{2} \end{align}\]Here, we encounter the first expectation that can be integrated in closed form for $g$ defined as the error function. Now, we introduce the useful expectations that will appear in the computation of expectations in the generalization error and order parameters:

\[\begin{align} I_{2}(a, b) & = \left< g(\nu_{a}) g(\phi_{b}) \right> \\ I_{3}(a, b, c) & = \left< g'(\nu_{a}) \phi_{b} g(\psi_{c}) \right> \\ I_{4}(a, b, c, d) & = \left< g'(\nu_{a}) g'(\phi_{b}) g(\psi_{c}) g(\gamma_{d}) \right> \\ J_{2}(a, b) & = \left< g'(\nu_{a}) g'(\phi_{b}) \right>~. \end{align}\]These expectations can be solved in closed form as a function of the covariance between each of the variables $\nu_ {a}, \phi_{b}, \psi_{c}$ and $\gamma_{d}$. Let’s start with an example from the terms in the generalization error. First, closed form expression for $I_{2}$, with $g$ as the Gauss error function, is

\[\begin{align} I_{2}(a, b) = & \frac{2}{\pi} \text{arcsin}\left( \frac{C_{ab}}{\sqrt{1 + C_{aa}} \sqrt{1+C_{bb}}} \right) \end{align}\]where $C_{ab}$ is the covariance between $\nu_{a}$ and $\phi_{b}$, and $C_{aa}$ and $C_{bb}$ are the variances of $\nu_{a}$ and $\phi_{b}$, respectively. The way to select the correct covariance structure, is to look at the arguments of the expectation. Recall the index notation, $i, j, k$ for the student, and $m, n, p$ for the teacher, then $a$ and $b$ can be any of these indices depending on the corresponding local field. For instance, if $a=k$, the notation implies that $\nu = \lambda$, if $b=m$, then $\phi = \rho$. From here, we can write the generalization error in terms of this integral

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{E} = & \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{K} \sum_{j=1}^{K} I_{2}(i, j) - \sum_{n=1}^{M} \sum_{i=1}^{K} I_{2}(i, n)+ \frac{1}{2} \sum_{m=1}^{M} \sum_{n=1}^{M} I_{2}(n, m) + \frac{\sigma^{2}}{2}~. \end{align}\]The covariances between the local fields are defined by the order parameters. For instance, the covariance for \(I_{2} (i, n)\) (student-teacher indexes) is \(C_{12} = R_{in}\), \(C_{11}=\text{diag}(Q)_{i}\) and \(C_{22}=\text{diag}(T)_{n}\), or the covariance for \(I_{2}(i, j)\) is \(C_{12}=Q_{ij}\), \(C_{11}=\text{diag}(Q)_{i}\) and \(C_{22}=\text{diag}(Q)_{j}\). In other words, the covariance structure for these expectation is given by the local field covariance, which are the order parameters. Hence, we can take advantage of broadcasting to compute all elements of \(I_{2}\) matrix as a function of the corresponding order parameters matrices:

def get_I2(c12, c11, c22):

e_c11 = jnp.expand_dims(jnp.diag(c11), axis=1)

e_c22 = jnp.expand_dims(jnp.diag(c22), axis=0)

denom = jnp.sqrt((1 + e_c11) * (1 + e_c22))

return jnp.arcsin(c12 / denom) * (2 / jnp.pi)

and the generalization error being

def order_parameter_loss(Q, R, T, sigma):

# Student overlaps

I2_1 = get_I2(Q, Q, Q)

first_term = jnp.sum(I2_1)

# Student teacher overlaps

I2_2 = get_I2(R, Q, T)

second_term = jnp.sum(I2_2)

# Teacher overlaps

I2_3 = get_I2(T, T, T)

third_term = jnp.sum(I2_3)

return first_term/2 - second_term + third_term/2 + sigma**2/2

$I_{3}$, $I_{4}$ and $J_{2}$ follow a similar structure, with the covariance structure defined by the order parameters between the arguments of the expectation. These integrals appear in the order parameters dynamical equation by expanding the error signal $\Delta_{s}^{u}$, giving

\[\begin{align} \frac{\mathrm{d}R_{in}}{\mathrm{d}t} & = \eta_{w} \left[ \sum_{m=1}^{M} I_{3}(i,n,m) - \sum_{j=1}^{K} I_{3}(i, n, j) \right] \\ \frac{\mathrm{d}Q_{ik}}{\mathrm{d}t} & = \eta_{w} \left[ \sum_{m=1}^{M} I_{3}(i,k,m) - \sum_{j=1}^{K} I_{3}(i, k, j) \right] \\ & + \eta_{w} \left[ \sum_{m=1}^{M} I_{3}(k, i, m) - \sum_{j=1}^{K} I_{3}(k, i, j) \right] \\ & + \eta_{w}^{2} \left[ \sum_{m, n}^{M} I_{4}(i, k, n, m) - 2 \sum_{j, n} I_{4}(i, k, j, n) + \sum_{j, l} I_{4}(i, k, j, l) + \sigma^{2} J_{2}(i, j) \right]. \end{align}.\]The closed form expression for all integrals $I_{3}$, $I_{4}$ and $J_{2}$ can be found in

Solvable learning dynamics for neural networks with a hidden layer

From the equations above, extending to a two-layer network (i.e., a network with a hidden layer) can be done simply by adding another layer to both the teacher and student networks. The second layer of the student network can be treated as an additional order parameter, as in Goldt et al.

where we introduce the second layer of the teacher and student as $v^{*}$ and $v$, respectively. The generalization error equation is also modified to include the second layer:

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{E} = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i,k}v_{i}v_{k}I_{2}(i,k) + \frac{1}{2}\sum_{n,m}v_{n}^{*}v_{m}^{*}I_{2}(n,m) - \sum_{i, n}v_{i}v_{n}^{*}I_{2}(i,n)~. \end{align}\]The derivation of these equations follow in the same way as the soft-committee machine with the only difference being the inclusion of the second-layer weights. Another way to understand the connection between both frameworks is by considering, for example, the soft committee machine as a two-layer network, where the second layer is fixed with ones in all its entries, i.e., \(v^{*}_{n}=1\) and \(v_{i}=1\) for all entries of each vector. At this point, the reader should be well-equipped to follow the derivation in

Replications

The code to reproduce all plots in this blog post can be found at https://anonymous.4open.science/r/nndyn-E763. The code is written as a Python package called nndyn and implemented in JAX to take advantage of vectorization and JIT-compilation. The code has three main components: tasks, networks, and ordinary differential equations (ODEs).

A task is defined by a teacher network, which is used to sample $(x, y)$ pairs for training the student network. A common workflow in the teacher-student setup involves first simulating a student network trained numerically with gradient descent. The resulting dynamics are then compared to the derived ODEs for the order parameters of the student network.

To simulate numerical training of a student network, the following pseudo-code can be used to define the teacher and student networks:

from nndyn.tasks import TeacherNetErrorFunc

from nndyn.networks import ErfTwoLayerNet, SoftCommettee

data = TeacherNetErrorFunc(batch_size=batch_size, W1=W1, W2=W2, seed=batch_sampling_seed,

additive_output_noise=additive_output_noise) # or sigma in the equations

if saad_solla:

true_student = SoftCommettee(layer_sizes=(input_dim, K, 1),

learning_rate=learning_rate,

batch_size=batch_size,

weight_scale=weight_scale,

seed=true_student_init_seed)

else:

true_student = ErfTwoLayerNet(layer_sizes=(input_dim, K, 1),

learning_rate=learning_rate,

batch_size=batch_size,

weight_scale=weight_scale,

seed=true_student_init_seed)

Then, the training loop can be defined as follows:

W1_list = []

W2_list = []

loss_list = []

for i in range(n_steps):

x, y = data.sample_batch()

if i % save_every == 0:

W1_list.append(np.array(true_student.W1))

W2_list.append(np.array(true_student.W2))

loss = true_student.update(x, y)

loss_list.append(np.array(loss))

For the ODE calculation, an ode object can be created, where each order parameter are simply attributes of this object, which can be moved forward in time using the update method:

from nndyn.odes import StudentEq, SoftCommetteeEq

# Initialize the student ODE object

if saad_solla:

ode = SoftCommetteeEq(init_W1=student_W1,

init_W2=student_W2, # These are defined as ones for the committee machine

learning_rate=learning_rate,

time_constant=dt,

teacher_W1=teacher_W1,

teacher_W2=teacher_W2, # These are defined as ones for the committee machine

sigma=additive_output_noise)

else:

ode = StudentEq(init_W1=student_W1,

init_W2=student_W2,

learning_rate=learning_rate,

time_constant=dt,

teacher_W1=teacher_W1,

teacher_W2=teacher_W2,

sigma=additive_output_noise)

order_parameter_loss = []

order_param_R = []

order_param_Q = []

order_parameter_W2 = []

save_every = 1000

for i in range(n_steps):

# Move order parameters forward in time by one dt step

# Every variable is on Jax, so it is useful to convert them to numpy arrays before saving

order_loss = ode.update()

order_parameter_loss.append(np.array(order_loss))

if i % save_every == 0:

order_param_R.append(np.array(ode.R))

order_param_Q.append(np.array(ode.Q))

order_parameter_W2.append(np.array(ode.student_W2))

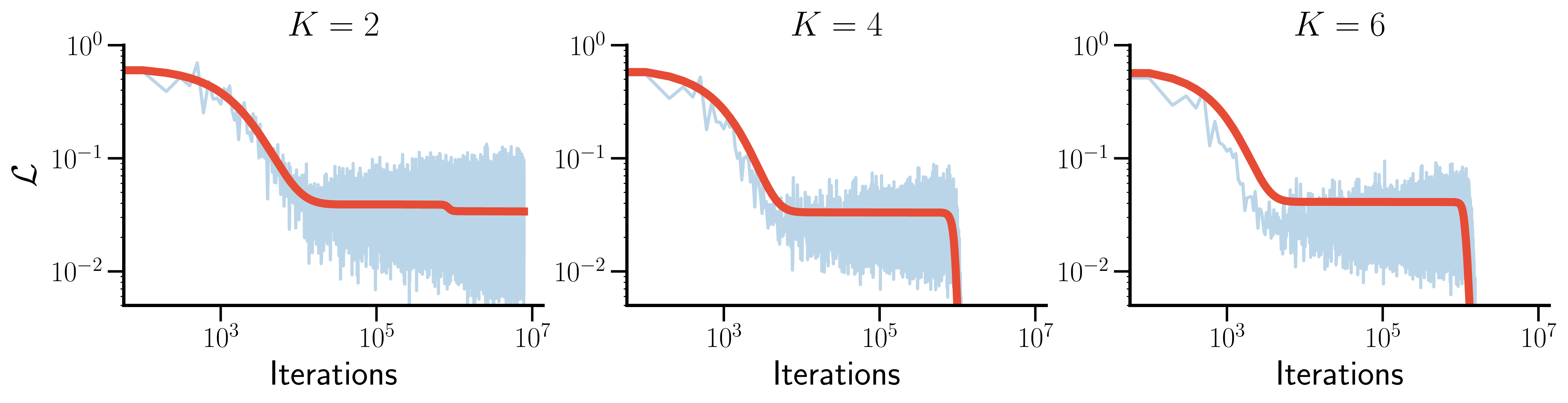

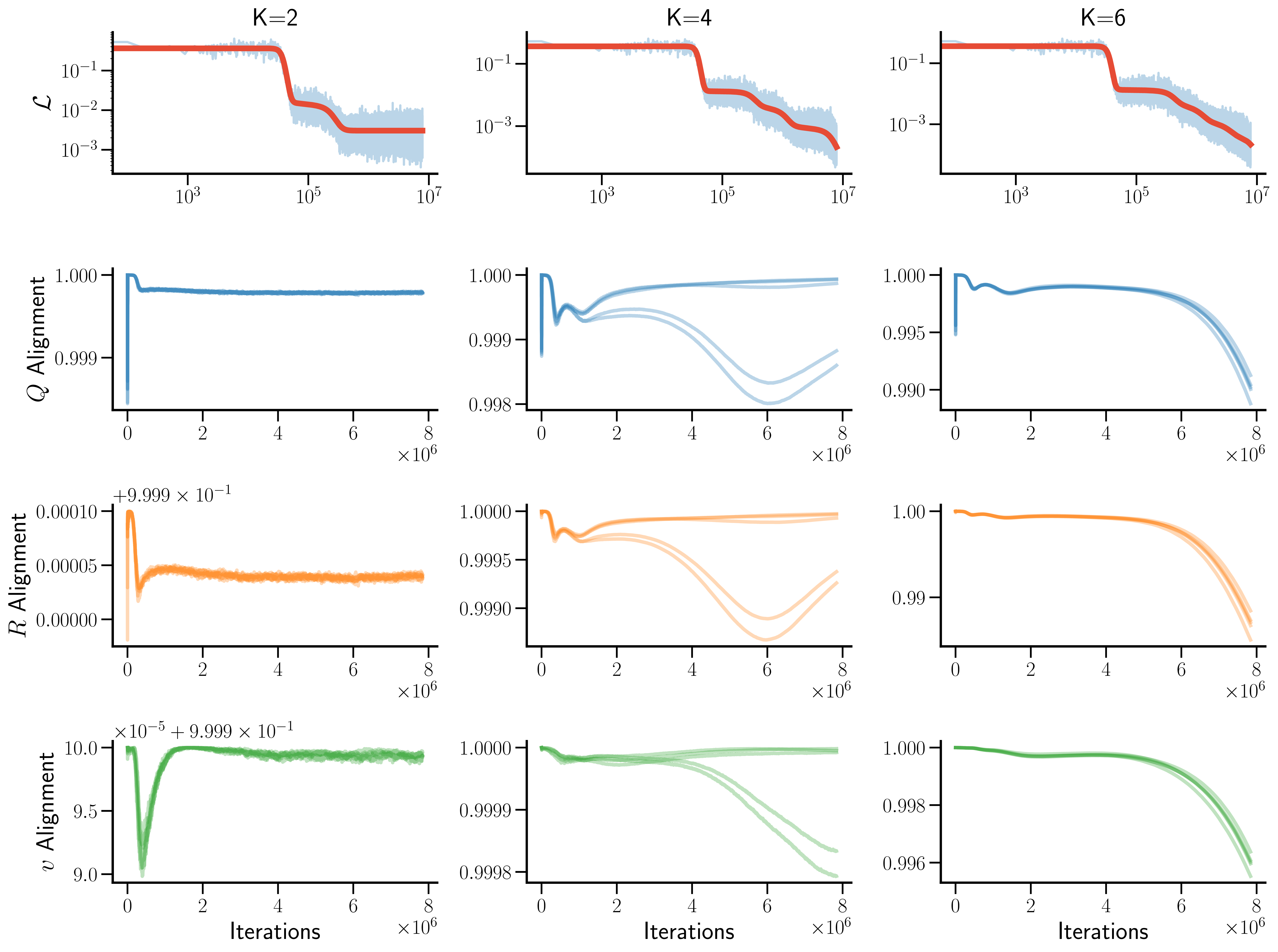

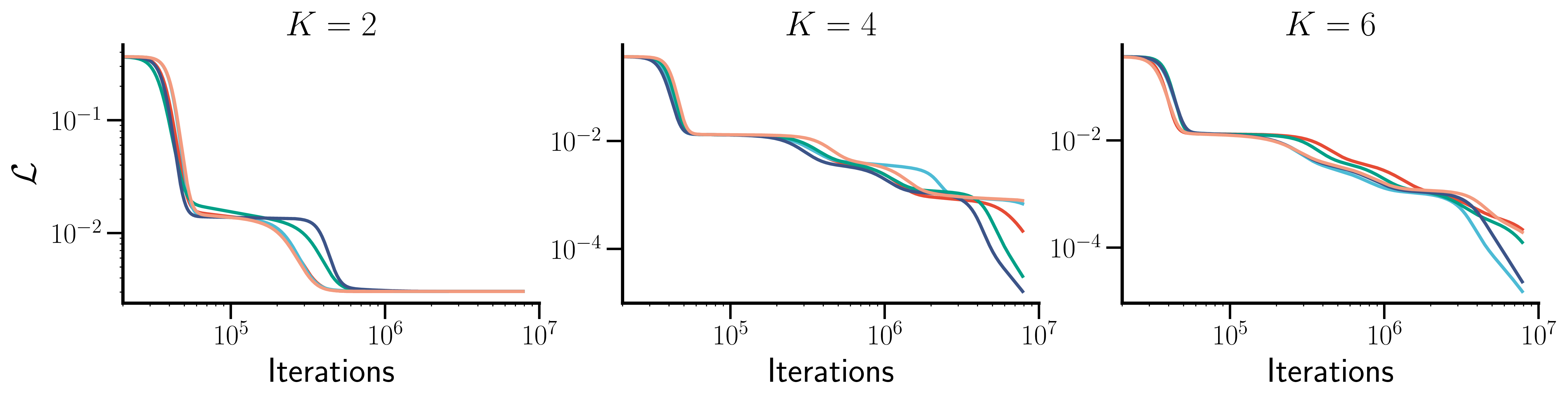

We now present results comparing simulations of the low-dimensional ODEs derived by Saad & Solla

Theory-experiment overlap in the soft committee machine

Theory-experiment overlap in neural networks with a hidden layer

Large initial weights produce individual differences

Discussion

The analytical techniques pioneered by Saad & Solla

Applications of the teacher-student setting

Beyond characterizing generalization error, the teacher-student framework has been applied to a wide range of problems, often to model interesting phenomena in machine learning. In optimization, applications extend to learning algorithms including natural gradient descent

The teacher-student framework has been used extensively to study the effect of task properties on learning dynamics via specific teacher parameterizations. Arnaboldi et al. developed quantitative measures of task difficulty

The analytical frontier

The statistical physics approach to neural network dynamics has expanded significantly beyond the early results of Saad & Solla

Recent work has tackled increasingly complex learning scenarios. Loureiro et al.

The Gaussian equivalence property

Conclusions

The mathematical tools of statistical physics have proven an important component to the development of neural networks, as noted by this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics

While the analytical teacher-student settings are simplified compared to modern deep learning systems, they nevertheless captures fundamental aspects of learning dynamics that persist in more complex architectures, including feature learning as characterized by the specialization transition. The extensions and applications surveyed here show how these theoretical tools continue to provide insights into problems ranging from optimization to continual learning. We hope that this blog post and the accompanying code repository make these results more accessible and extensible to the broader machine learning community.

Code availability

The code to reproduce all plots in this blog post can be found at https://anonymous.4open.science/r/nndyn-E763. This codebase is also easily adaptable to explore the learning dynamics of neural networks in the teacher-student setting beyond the scope of this blog post.