Fair Model-Based Reinforcement Learning Comparisons with Explicit and Consistent Update Frequency

Implicit update frequencies can introduce ambiguity in the interpretation of model-based reinforcement learning benchmarks, obscuring the real objective of the evaluation. While the update frequency can sometimes be optimized to improve performance, real-world applications often impose constraints, allowing updates only between deployments on the actual system. This blog post emphasizes the need for evaluations using consistent update frequencies across different algorithms to provide researchers and practitioners with clearer comparisons under realistic constraints.

Introduction

In reinforcement learning

There are two main approaches when designing a reinforcement learning algorithm: model-based or model-free. Model-based reinforcement learning (MBRL) algorithms

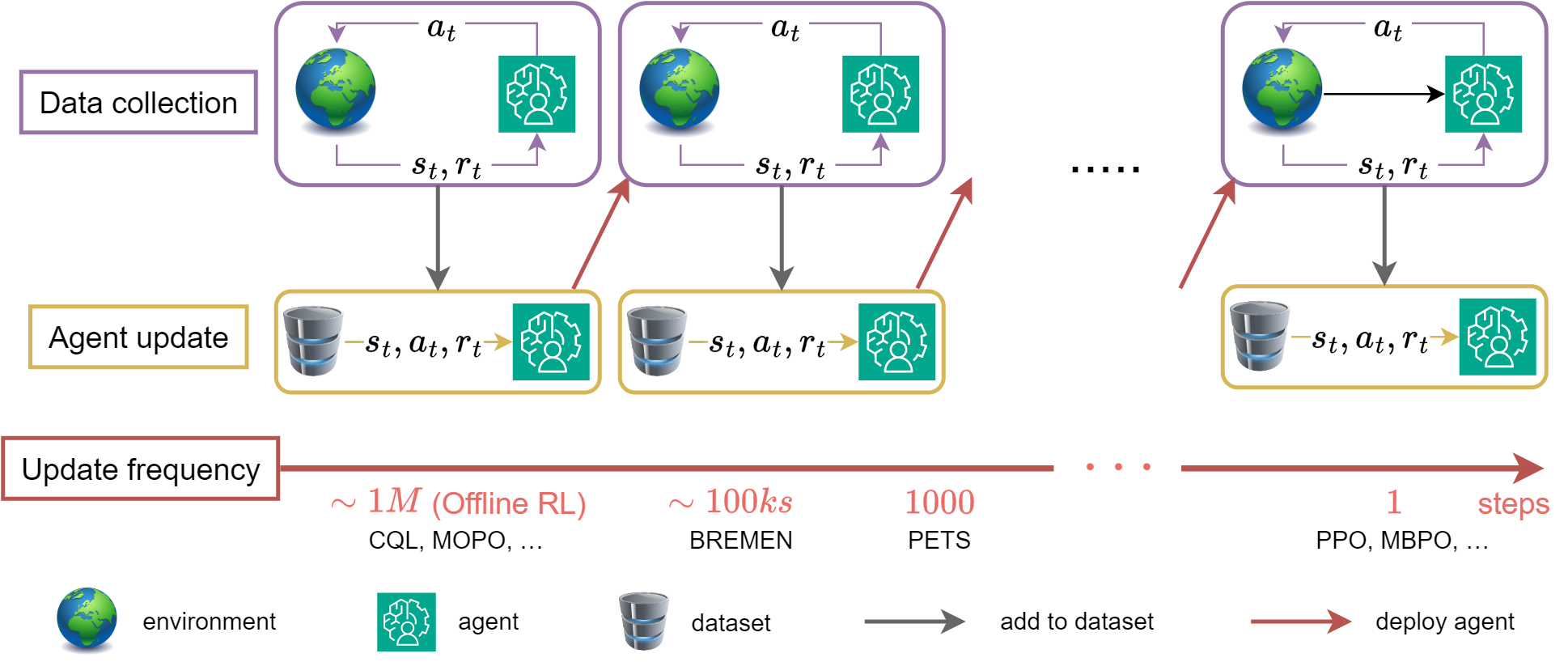

We discuss here about one of the design choices of MBRL algorithms: the update frequency of the agent. As shown in the figure below

The update frequency is often viewed as yet another hyperparameter of the complex MBRL pipeline. However, in practice the update frequency may be imposed by real-life deployment constraints, motivating the discussions of this blog post. It is often the case that for safety reasons, system engineers agree to run a new agent on their system for a given period of time but prefer the agent to be fixed during this deployment, as

Given the importance of the update frequency in real-life applications, this blog post advocates for:

- explicitly specifying the update frequency employed by each algorithm in a benchmark, as this remains implicit and hard to find in many existing benchmarks,

- conducting additional experiments that compare algorithms under a given update frequency, mirroring the constraints often encountered in real-life applications, and

- performing more ablation studies on update frequency, evaluating its impact on algorithm performance.

For the rest of this blog post, we define a deployment as a data collection campaign realized with a fixed agent. The agents are thus updated between two consecutive deployments but not within one deployment. The update frequency is the number of steps realized at each deployment (that we assume fixed for all deployments). We use the term agent to refer to all the components of the model-based algorithm that are used to act on the system. For instance, in a Dyna-style algorithm

We begin by introducing three popular MBRL algorithms (MBPO, PETS and BREMEN) as we will often refer to them to illustrate our arguments.

Three popular MBRL algorithms

The following table gives an overview of the update frequency of the three algorithms we discussed below and few others. This table is not meant to provide an exhaustive list of all the MBRL algorithms but rather to give an idea of the different training schedules that are used in the literature.

| Algorithm | Agent update frequency | Policy update frequency | Model update frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBPO | 1 step | 1 step | 250 steps |

| PETS | Task Horizon | No policy | Task Horizon |

| PILCO | Task Horizon | Task Horizon | Task Horizon |

| BREMEN | 100k or 200k steps | 100k or 200k steps | 100k or 200k steps |

| ME-TRPO | 3k or 6k steps | 3k or 6k steps | 3k or 6k steps |

MBPO

Model-based Policy Optimization (MBPO)

PETS

Probabilistic Ensemble and Trajectory Sampling (PETS)

BREMEN

Behavior-Regularized Model-ENsemble (BREMEN)

We now detail the main arguments of our blog post: making the update frequency more accessible, designing benchmarks with fixed update frequencies and running ablation studies on the update frequency.

Making the update frequency more accessible

Experiments done in popular papers do not always explicit the update frequencies they use for each of the algorithms they run. When nothing is said, it is very likely that most of the times the benchmarks are using the original implementation of the algorithms, shared by the authors of the algorithms in the best case. For instance the MBPO paper

The difficulty in knowing the update frequencies used in benchmarks makes it harder for the researchers and practitioners to take this parameter into account to assess the performance of the algorithms and whether they would be good candidates for their real-life applications. It also demands much more investigation from the reader to know what the authors used.

MBRL algorithms have an order of magnitude more meaningful hyperparameters than supervised models, and managing and reporting on them usually falls out of the scope of research papers. The practice of sharing the code alleviates this issue somewhat, and should be saluted, since we can always dig up in the code what the parameters were. However, ideally, choices that drastically change the performance of the algorithms, should be made explicit as much as possible in the research papers and the ablation studies.

Comparisons with fixed update frequency

We want to make the community aware of the importance of the update frequency when comparing algorithms and when designing benchmarks. Running benchmarks without any constraints allows using different update frequencies for each algorithm. We believe that such benchmarks are valuable for the community. However it would also be very informative for the community to have benchmarks with comparable update frequencies between the algorithms. This would for instance help to find the potentially best algorithms for real applications with constraints on the update frequency.

Coming back to the experiments run in MBPO’s paper, as the default MBPO implementation updates the model each 250 steps, it might also make sense to allow PETS to be updated each 250 steps as well to have comparable results. We also note that the MBRL-Lib paper

The BREMEN paper

Ablation studies

Comparisons of different update frequencies are very rare in existing benchmarks and existing papers. Even without real-life constraints it would be valuable to know how sensitive the performance of a given algorithm is with respect to the update frequency. The issue for the authors is that this could be asked for many other hyperparameters and represent additional computational budget and time. However we often find ablations on the number of models (if the model is an ensemble), the rollout length, the number of gradient updates for the model-free policy, but very rarely on the update frequency. It is very likely that the agents that are good for small deployments would be bad for large deployments, a setting that would tend to be closer to the pure offline setting (for the same total budget of real system interactions). We perform such an ablation study using MBPO in the next section, showing that MBPO’s performance is degrading with larger update frequencies.

Varying the update frequency in MBPO

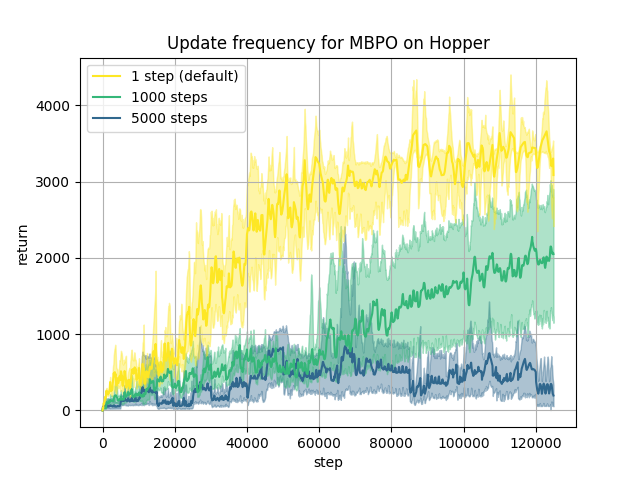

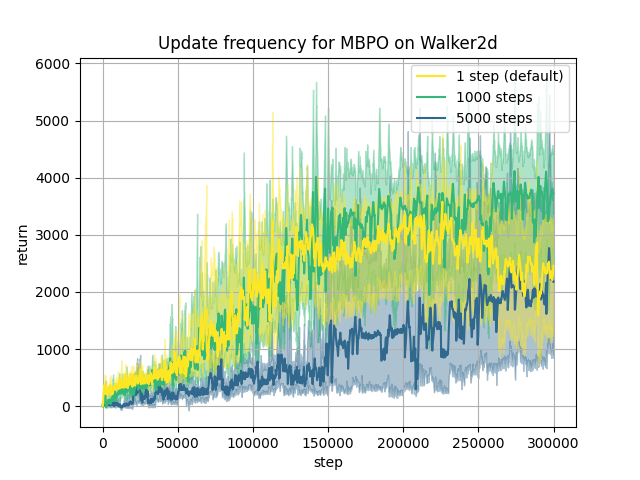

Using the MBPO implementation and the examples provided by MBRL-Lib

Except for the update frequency of 1000 steps on Halfcheetah and Walker which achieves similar performance than the default configuration updating the agent at each step, the results indicate a decline in asymptotic performance with larger update frequencies. Although MBPO exhibits good performance over different environments for the default update frequency, this is not the case for the other update frequencies that we consider here. We note here that 1000 steps is the usual maximum episode length and therefore a reasonable value to try for the update frequency. One insight from this experiment is that even though MBPO is one of the state-of-the-art MBRL algorithms, practical constraints like the update frequency can potentially alleviate its performance in real-world applications.

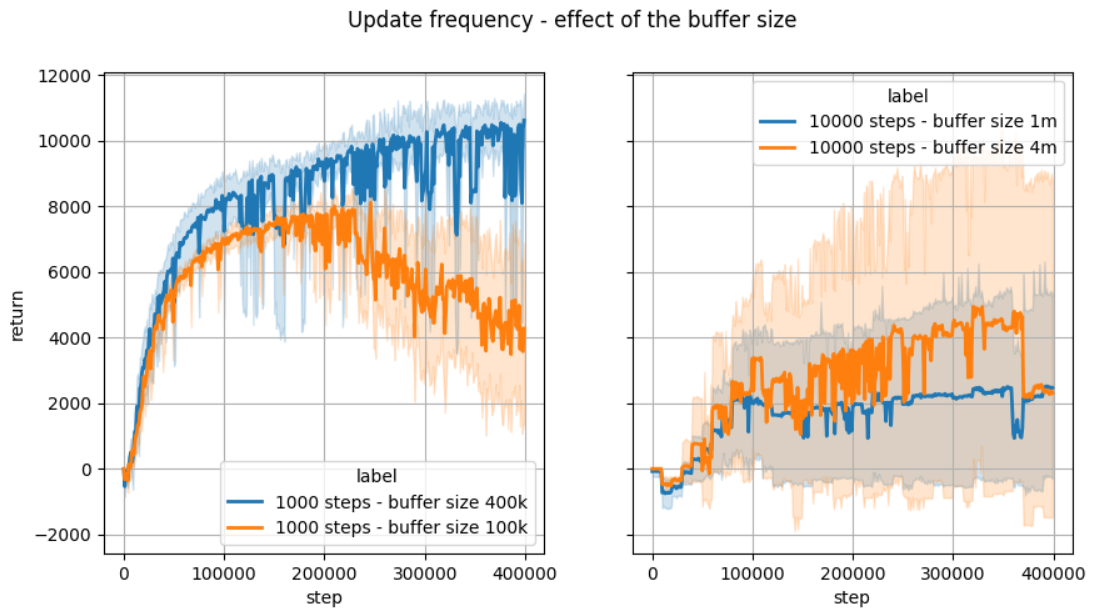

When trying these values of updates frequencies we adjusted the number of gradient steps to maintain a constant ratio of gradient steps per step on the real system. For the maximum buffer size of SAC we used the rule provided in MBPO’s code. The table below shows the values obtained for the maximum buffer size. As shown in the figure below, using a smaller buffer size negatively impacts the performance for the update frequency of 1000 steps and 10 000 steps. While there is a possibility that better values for the hyperparameters (other than the update frequency) could be found, we did what appeared to be the natural way to adapt the other hyperparameters when increasing the update frequency. See the Appendix for the complete description of the hyperparameters used in these experiments.

| Agent update frequency | Model update frequency | Policy update frequency | Max SAC buffer size |

|---|---|---|---|

| default (1 step) | 250 | 1 | 400 000 |

| 1 000 steps | 1000 | 1000 | 400 000 |

| 5 000 steps | 5000 | 5000 | 2 million |

| 10 000 steps | 10 000 | 10 000 | 4 million |

Conclusion

The goal of this blog post is to shed light on a frequently overlooked hyperparameter in MBRL: the update frequency. Despite its importance for real-life applications, this parameter is rarely discussed or analyzed. We emphasize the importance of running more evaluations using consistent update frequencies across different algorithms and more ablation studies. We for instance show how the update frequency impacts the performance of MBPO. Similar to the update frequency, we can identify several other hyperparameters that deserve more attention when benchmarking different MBRL algorithms. A typical example is the continual training (of the model and/or policy) versus retraining from scratch (referred to as the primacy bias in some previous work

Appendix

We provide here the configuration files we used to run the different experiments.

Halfcheetah

- Update frequency of 1000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___HalfCheetah-v4"

term_fn: "no_termination"

num_steps: 400000

epoch_length: 1000

num_elites: 5

patience: 5

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 1000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 1]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 10000

sac_updates_every_steps: 1000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 1

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: true

sac_target_entropy: -1

sac_hidden_size: 512

sac_lr: 0.0003

sac_batch_size: 256

- Update frequency of 5000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___HalfCheetah-v4"

term_fn: "no_termination"

num_steps: 400000

epoch_length: 5000

num_elites: 5

patience: 5

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 5000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 1]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 50000

sac_updates_every_steps: 5000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 1

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: true

sac_target_entropy: -1

sac_hidden_size: 512

sac_lr: 0.0003

sac_batch_size: 256

- Update frequency of 10000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___HalfCheetah-v4"

term_fn: "no_termination"

num_steps: 400000

epoch_length: 10000

num_elites: 5

patience: 5

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 10000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 1]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 100000

sac_updates_every_steps: 10000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 1

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: true

sac_target_entropy: -1

sac_hidden_size: 512

sac_lr: 0.0003

sac_batch_size: 256

Hopper

- Update frequency of 1000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___Hopper-v4"

term_fn: "hopper"

num_steps: 125000

epoch_length: 1000

num_elites: 5

patience: 5

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 1000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 15]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 40_000

sac_updates_every_steps: 1000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 4

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: false

sac_target_entropy: 1 # ignored, since entropy tuning is false

sac_hidden_size: 512

sac_lr: 0.0003

sac_batch_size: 256

- Update frequency of 5000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___Hopper-v4"

term_fn: "hopper"

num_steps: 125000

epoch_length: 1000

num_elites: 5

patience: 5

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 5000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 15]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 200000

sac_updates_every_steps: 5000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 4

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: false

sac_target_entropy: 1 # ignored, since entropy tuning is false

sac_hidden_size: 512

sac_lr: 0.0003

sac_batch_size: 256

Walker

- Update frequency of 1000 steps

# @package _group_

env: "gym___Walker2d-v4"

term_fn: "walker2d"

num_steps: 300000

epoch_length: 1000

num_elites: 5

patience: 10

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 1000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 400

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 1]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 20000

sac_updates_every_steps: 1000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 4

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: false

sac_target_entropy: -1 # ignored, since entropy tuning is false

sac_hidden_size: 1024

sac_lr: 0.0001

sac_batch_size: 256

- Update frequency of 5000 steps We only used a maximum buffer size of 1 million to limit the memory usage of this experiment.

# @package _group_

env: "gym___Walker2d-v4"

term_fn: "walker2d"

num_steps: 300000

epoch_length: 1000

num_elites: 5

patience: 10

model_lr: 0.001

model_wd: 0.00001

model_batch_size: 256

validation_ratio: 0.2

freq_train_model: 5000

effective_model_rollouts_per_step: 200

rollout_schedule: [20, 150, 1, 1]

num_sac_updates_per_step: 100000

sac_updates_every_steps: 5000

num_epochs_to_retain_sac_buffer: 1

sac_gamma: 0.99

sac_tau: 0.005

sac_alpha: 0.2

sac_policy: "Gaussian"

sac_target_update_interval: 4

sac_automatic_entropy_tuning: false

sac_target_entropy: -1 # ignored, since entropy tuning is false

sac_hidden_size: 1024

sac_lr: 0.0001

sac_batch_size: 256