Understanding gradient inversion attacks from the prior knowledge perspective

In this blogpost, we mention multiple works in gradient inversion attacks, point out the chanllenges we need to solve in GIAs, and provide a perspective from the prior knowledge to understand the logic behind recent papers.

Federated learning, as a way to collaboratively train a deep model, was originally developed to enhance training efficiency and protect data privacy. In a federated learning paradigm, no matter whether it is horizontal or vertical, data could be processed locally, and the central server could only get access to the processed information, such as trained model weights or intermediate gradients

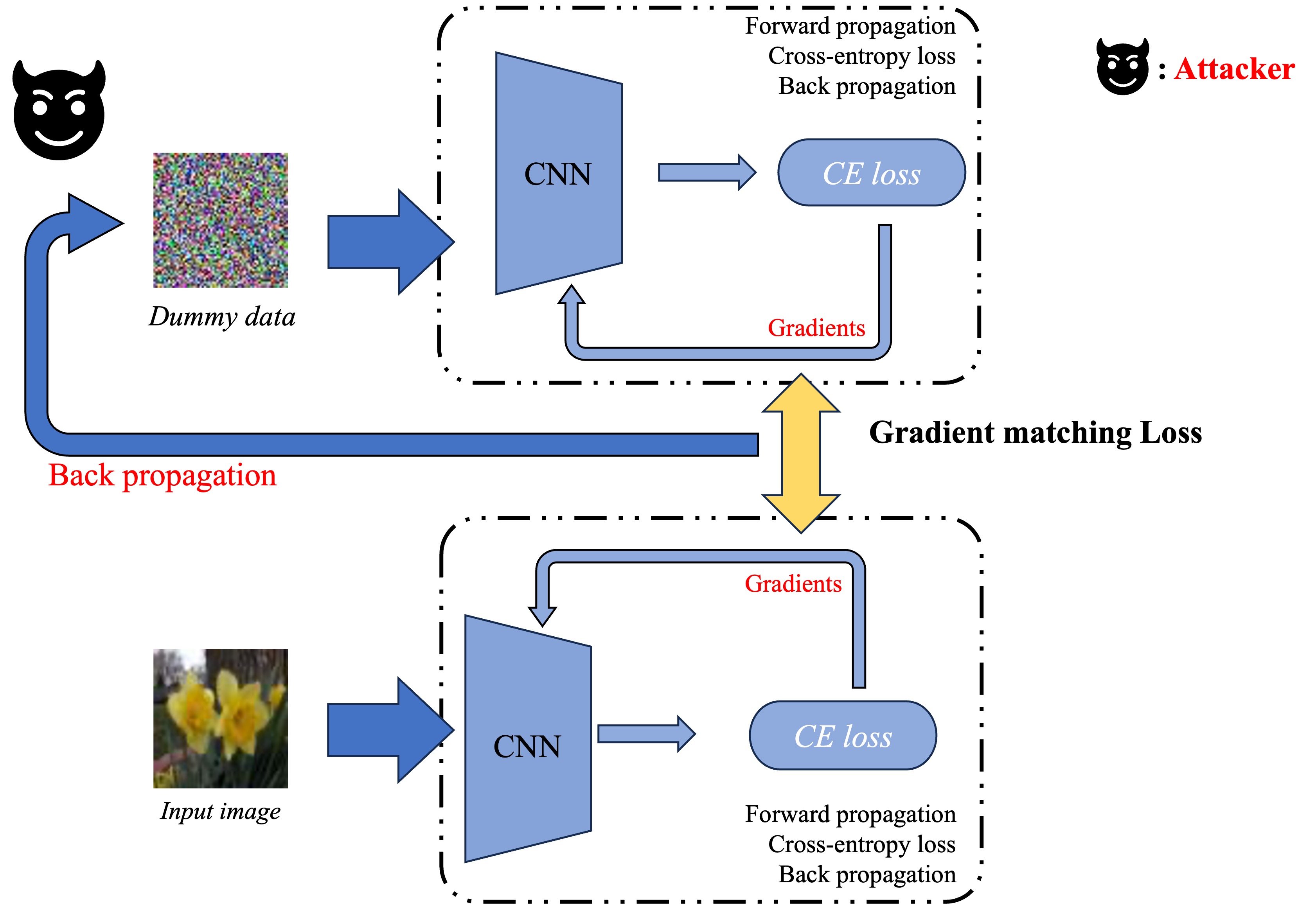

Fundamental pipeline of Gradient inversion attacks (GIAs)

Gradient inversion attacks (GIAs) aim at reconstructing clients’ private input data from the gradients in deep neural network training phases. It is a threat to federated learning framework, especially the horizontal one where a curious-but-honest central server collects gradients from multiple clients, analyzes the optimal parameter updating direction, and sends back the updated model in one step. Getting rid of complicated mathematical formulas, GIA is actually a matching process: the attacker (which is the central server in the most common settings) expects that the data it randomly initialized could finally generate the identical gradients as the ground truth, therefore it measures the difference (or distance) to optimize input data pixel-wisely. The smaller the distance between gradients, the better the private data are reconstructed.

This is a white-box attack, for its requirement for full model parameters to conduct backpropagation. In such a process, with fixed model parameters, the distance between gradients is highly dependent on the attacker’s dummy data. GIA’s target is to optimize the distance below, where $x^\ast$ and $y^\ast$ represent the dummy data-label tuple, $\mathcal{D}$ represents the distance function, $\theta$ represents the model weights, and $\mathcal{L}$ represents the CE loss.

\[\arg\min \limits_{(x^*,y^*)} {\mathcal{D}}\left(\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}_\theta\left( x,y\right),\nabla_\theta\mathcal{L}_\theta\left( x^*,y^*\right)\right)\]After raising this problem, there are a few research topics in this field. iDLG

The tough challenge in GIAs

In GIA, the tough challenge, which has not been solved yet, is the reconstruction of batched input data, where multiple samples share the same labels. Previous works headed towards such a goal by a few steps: they first recovered single input data, then extended them to batches with known labels, and added a new algorithm to recover batched one-hot labels before recovering input images. However, to the best of my knowledge, it is still limited to the situation where for every class there could be at most one sample in a batch. Batched data recovery with repeated labels is still a failure for all current algorithms. The key reason for this failure lies in the information discard of averaged gradients.

A simple example of information discards

Let’s first take a look at a simple neural network: MLP. In a specific layer, it takes in intermediate features $\mathbf{x}$ and outputs a result of matrix multiplication $\mathbf{z}=\mathbf{Wx}+\mathbf{b}$. To recover the input from gradients, we could simply use the bias attack

In the above equation, it is clear that for a single input, with full access to model weights and gradients, the gradients of the MLP contain full information to execute single-image recovery.

Here, we conduct a simple experiment to illustrate the existence of information discard. Firstly We pick a 4-layer MLP as the target neural network and randomly select a few images from the Flowers-17 dataset as the private input data for recovery. We take $l_2$ lossbatchsize=1 with known labels.

It is not surprising that $l_2$ gradient matching functions could recover the input data well. Such a good performance is mainly because MLP’s gradients contain enough information of intermediate features for single inputs. With proper labels, we could conclude that GIA works well on MLP when batchsize=1.

However, when it comes to CNNs, such inversion gets harder. For convolution layers, the gradients of convolution kernels are aggregated through the whole feature map, therefore even if we set batchsize=1, gradients may still experience information discards, affecting the attack performance. This problem is also mentioned in R-GAPbatchsize=1. Ground-truth one-hot labels are provided.

It is clear that even though both functions could recover the image, there are some pixels not perfectly optimized, indicating the existence of information discards. If we change the batchsize, even if we only slightly enlarge it as batchsize=2, such reconstruction ends up with a failure.

For a given network, the size of gradients is fixed. Therefore, with the increase in batchsize, GIA will experience more obvious information discards. This is easy to understand, and researchers designed a few ways to complement this loss.

Understanding GIAs from the prior knowledge perspective

Realizing the information discards, reviewing the recent paper through the prior knowledge perspective may help understand the logic better. To achieve better image reconstruction quality, it is natural to consider the prior knowledge of images as the complement. Here, the prior knowledge could be explained in three aspects.

Unparameterized regularization terms

In IG

To further illustrate the benefits such regulariztaion terms have on the data reconstruction processes, here is an example of adding total variance for batchsize=2 image reconstruction. The scale of total variance ranges from \(10^{-4}\) to \(10^{-1}\).

With identical learning rate, images with higher total variance are reconstructed faster. Because the total variance penalizes obvious distinctions for adjacent pixels, images with higher total variance are also more blurred. On the other side, reconstructions with insufficient total variance fail to generate recognizable images.

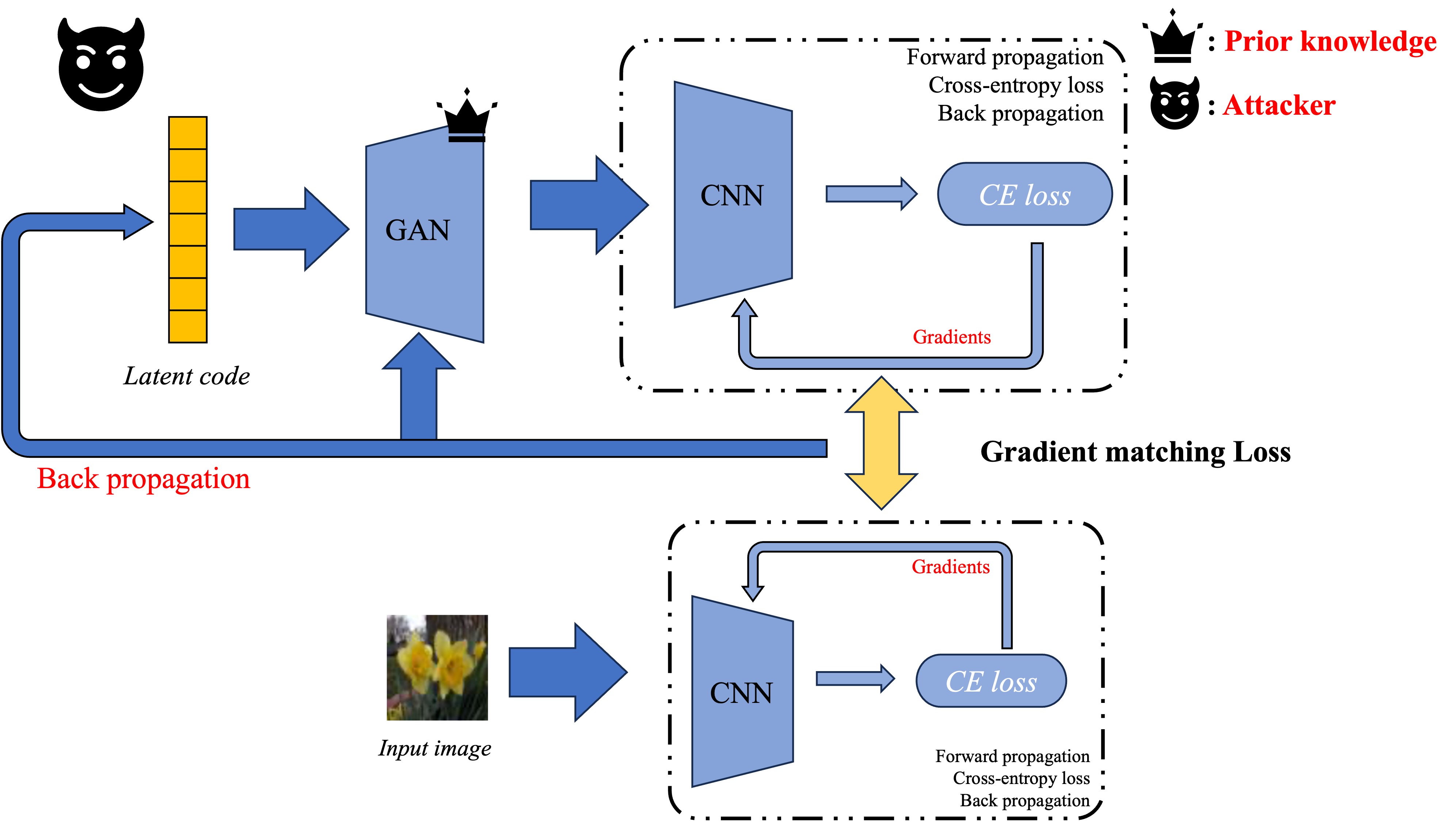

Generative models

Keep following the logic that recent works require some other conditions as prior knowledge to reinforce the information discards from gradients, generative models, especially GANs, could serve as a strong tool to encode what “real images” should be. The way to add GAN’s generator in gradient matching processes is simple

Recent work GIFD

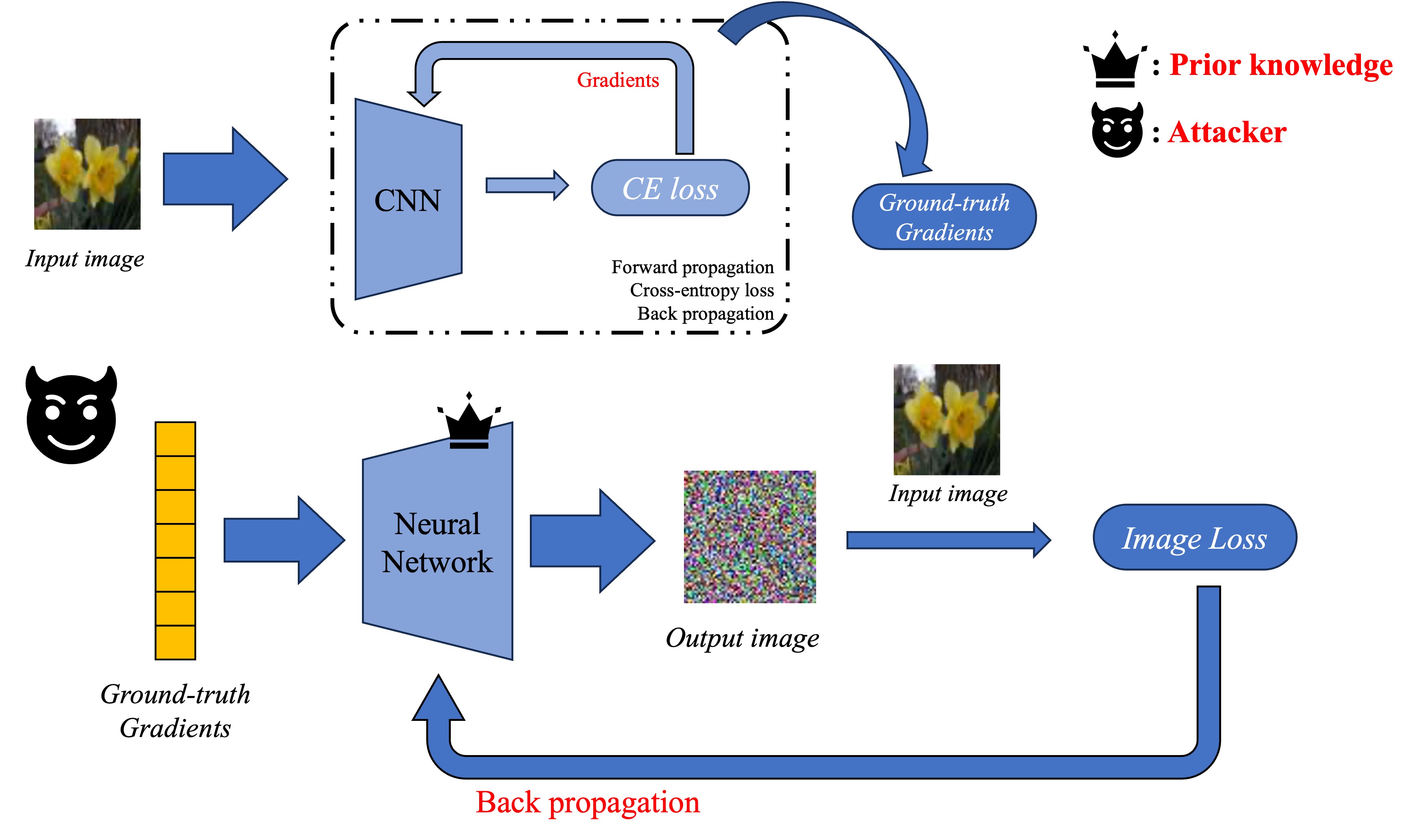

End-to-end networks

Actually, the most intuitive way to conduct a GIA is to design a function that takes gradients as input and then outputs recovered images. For a target network, image-gradient tuples are easy to collect, therefore the prior knowledge could be encoded in such an end-to-end neural network through model training.

Here, the neural network resembles a GAN generator which takes in representation vectors and outputs a synthesized image. However, instead of abstract latent codes, such a network receives gradient vectors to generate images. In implementations, Wu et.al

Limitation and future directions

For GIAs that require pre-trained models, the key limitation is the auxiliary dataset. It is kind of unrealistic to claim that the dataset used for pretraining generative models (or end-to-end models) shares the same distribution with the unknown private input data, and possibly, with distinct dataset distribution, the generative performance may experience a drop. Both GIAS and GIFD use GAN with in-distribution auxiliary data to compare with previous state-of-the-art works, and GIFD paper only shows the reconstruction result of distinct distribution data when batchsize=1 with the same label space. For the most general situation where the attacker has limited knowledge of the potential distribution of the private data, it may be still hard to recover high-quality batched data with generative networks. Considering these limitations, it is of great value to explore algorithms to learn some general prior knowledge, especially those robust among different data distributions.

Conclusions

- The existence of information discards in gradient aggregation is the tough challenge of GIAs.

- From the prior knowledge perspective, previous GIA works provide three ways to complement information discards.

- It may still be hard to recover batched data from gradients with limited knowledge of private data distribution.