It's Time to Move On: Primacy Bias and Why It Helps to Forget

'The Primacy Bias in Deep Reinforcement Learning' demonstrates how the first experiences of a deep learning model can cause catastrophic memorization and how this can be prevented. In this post we describe primacy bias, summarize the authors' key findings, and present a simple environment to experiment with primacy bias.

Introduction to Primacy Bias

Primacy bias occurs when a model’s training is damaged by overfitting to its first experiences. This can be caused by poor hyperparameter selection, the underlying dynamics of the system being studied, or simply bad luck.

In this post we explore the paper “Primacy Bias in Deep Reinforcement Learning” by Nikishin et al. and presented at ICML 2022

Like many deep learning concepts, primacy bias takes inspiration from psychology

Off Policy Deep Reinforcement Learning

Nikishin et al. discuss a specific type of model that is particularly sensitive to primacy bias: off-policy deep reinforcement learning. Here, the goal is to learn a (policy) that makes good decisions in an interactive environment. Off-policy algorithms achieve this by separating decision-making from learning. Deep Q-Learning (DQN)

- Data Collection: use the current policy to interact with the environment and save memories to a dataset called the replay buffer.

- Learning: sample from the replay buffer to perform gradient updates on the policy.

Are we Overcomplicating?

For those without a reinforcement learning background, this might seem needlessly complicated. Why can’t we simply explore with a random policy and then fit a model all at once?

Although this is sometimes done

Selecting a Replay Ratio

The replay ratio is the total number of gradient updates per environment interaction. If the number of experiences is fixed, then modifying the replay ratio is equivalent to changing the number of training epochs in a typical deep learning problem.

Most researchers know the importance of training for a sufficient number of epochs. Training for more epochs is preferred and methods such as early stopping, weight regularization, and dropout layers can mitigate the risk of overfitting. At worst, if you end up with an overfit model then you can retrain it from scratch.

In deep reinforcement learning, the replay ratio is typically set to one. Unfortunately, finding the correct replay ratio is difficult. We want the agent to learn as much as possible but there is a path-dependency that is hard to ignore. If the policy becomes overfit early it will have less meaningful interactions with the environment, creating negative feedback. If you don’t catch overfitting in your Poker Bot until it loses a couple tournaments, then you might have spent a lot of money for a dataset on how to lose poker hands.

Heavy Priming

To quantify this, Nikishin et al. perform an experiment with heavy priming. The goal is to train an agent on the “quadruped-run” environment, where an agent learns to manipulate joint movement to travel forward.

First, a baseline is trained with default parameters. Next, to create heavy priming, the agent collects 100 interactions and then trains for 100K steps. The model with heavy priming fails to ever recover in an example of catastrophic memorization.

Weight Resets

To avoid primacy bias, Nikishi et al. propose the following solution: freely increase the replay ratio, but periodically perform a weight reset to reinitialize all of the agent’s weights while preserving the replay buffer. This destroys any learned information in the network’s weights. At worst, if there is no primacy bias, the replay buffer will contain enough information to retrain to the previous weights. At best, primacy bias is eliminated, and the model finds a new optima.

To think about this concretely, consider a 100 step training loop. At each step we:

- Gather 1 observation.

- Add it to the replay buffer.

- Select a random sample from the replay buffer.

- Perform a gradient update to the model with the sample.

After 100 steps, the first observation will have been sampled on average 5.19 times. The 50th observation will have been sampled 0.71 times, and the 99th observation will have been sampled on average 0.01 times. This can be summarized in a plot.

Some solutions to mitigate this include recency weighting

In practice, weight resets are a bit more complicated. Ideally, we retrain the model from scratch after each observation. Unfortunately this isn’t realistic (on my computer). This leaves us with two decisions:

- Select a reset frequency.

- Decide what to reset.

Resetting often will prevent primacy bias but this requires a high replay ratio. This trade-off is discussed in detail in the follow up work “Sample-Efficient Reinforcement Learning by Breaking the Replay Ratio Barrier”

Do Resets Work?

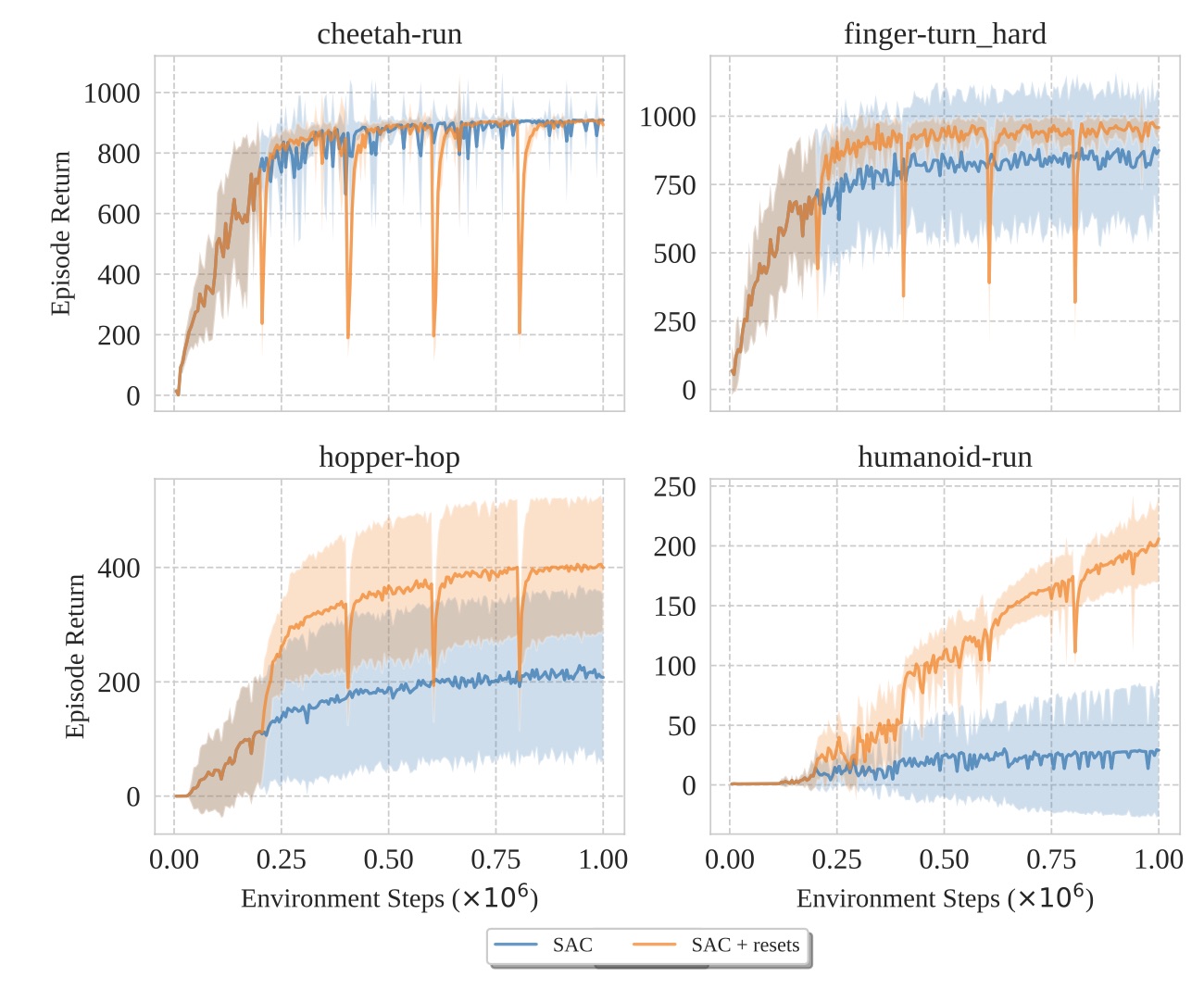

Nitkshi et al. show that on average resets work well.

- Immediately after a reset there is a sudden drop in performance that quickly recovers.

- Resets never irreparably harm a model. At worse, the model returns to the pre-reset level (ex: cheetah-run), but sometimes it can perform substantially better (humanoid-run).

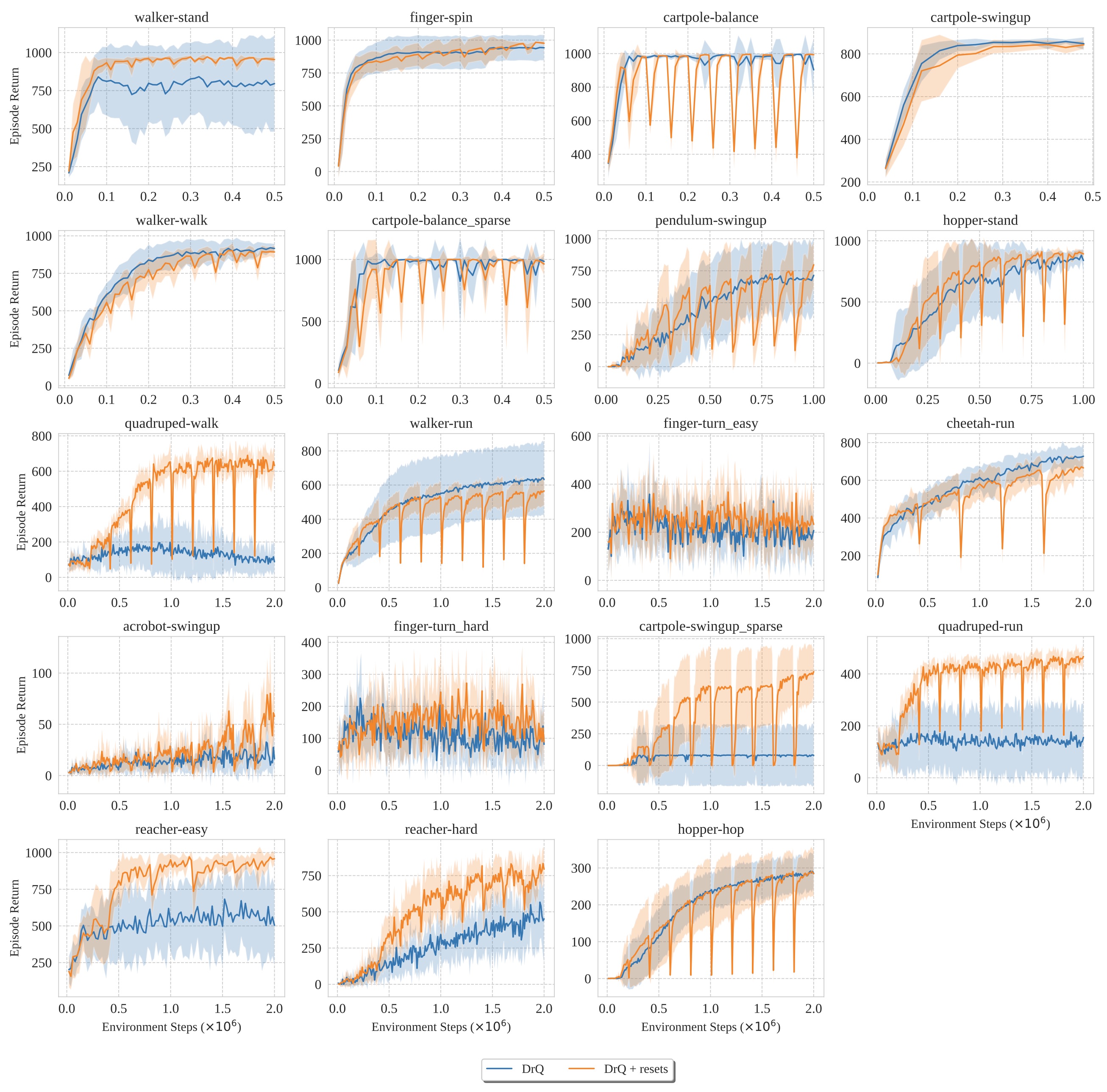

These results are consistent across multiple algorithms and environments, including the continuous control Deep Mind Control Suite and the discrete Atari 100k benchmarks.

Episode return overtime on a subset of DeepMind Control, with and without resets, using SAC algorithm. Averaged over 10 random seeds.

Episode return overtime in DeepMind Control, with and without resets, using the DRQ algorithm. Averaged over 20 random seeds.

Per-game scores in Atari, with and without reset, using the SPR algorithm. Averaged over 20-100 random seeds.

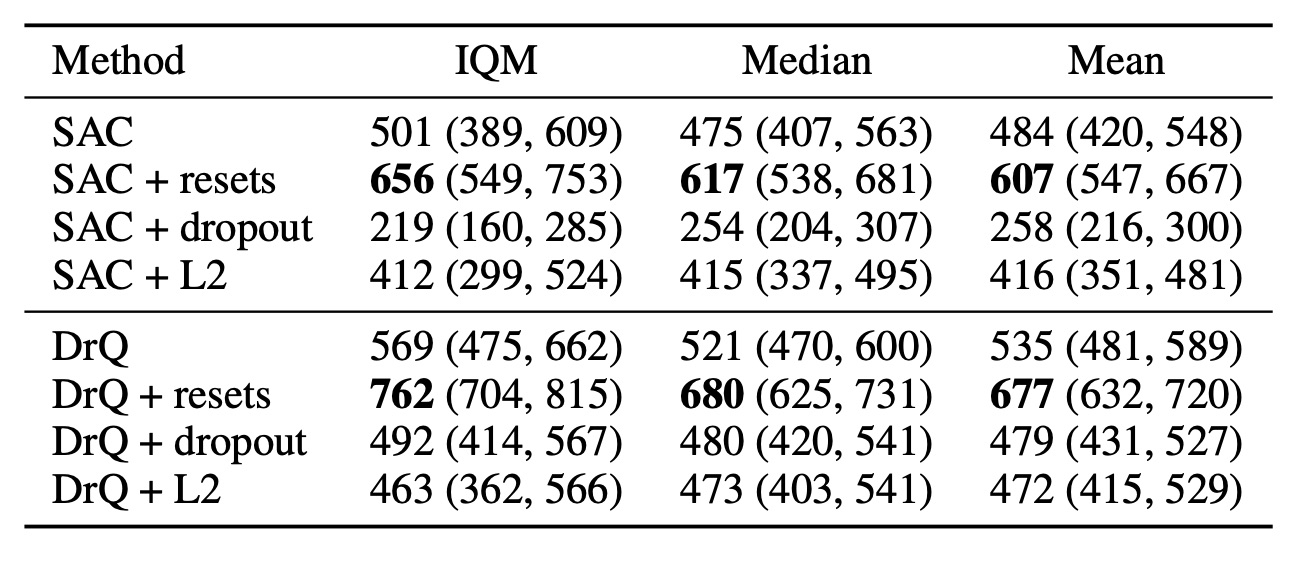

After seeing the success of resets, it is reasonable to wonder how weight resets compare to other regularization tools. The authors test this as well and show that resets improve outcomes in their experiments on average more than either dropout or L2 regularization (which actually perform worse than the baseline).

What’s The Catch?

While these results are impressive, they come at a cost. At minimum, increasing the replay ratio increases the compute time linearly. D’Oro et al 2023

Additionally, implementing weight resets requires a sneaky number of design decisions. The results from the paper show reset rules specifically chosen for each environment and algorithm.

Some of these considerations include:

- How often should you reset? Every step is ‘ideal’ but it is also ideal to get results this year.

- What is the optimal replay ratio to maximally learn per sample and sustain the reset frequency?

- What exactly should I reset? Full model? Last layer?

These are open questions. For weight resets to become widely used new heuristics and best practices will need to develop. The answers may depend on both the network architecture and the underlying system dynamics. Trying to imagine the precise behaviours induced by primacy bias on Atari and Deep Mind Control can be difficult.

Implementing Primacy Bias

The best way to learn something is through practice. In this section we will present a minimum example of primacy bias. The associated code is released as a notebook along with additional experiments.

The biggest obstacle to studying primacy bias is the compute required. Training time scales linearly with replay ratio, and a high replay ratio is necessary to extract maximal information per sample and to recover after each reset. To work around this, we present an MVP: Minimum Viable Primacy (bias).

We use a modified version of the Frozen Lake environment provided by Farama Gymnasium

2x2 Switching Frozen Lake

Frozen Lake is a simple pathfinding problem. The model receives a reward if it successfully traverses a grid to reach a goal. The model can fail in two ways: 1) it falls in a hole or 2) it takes too long to reach the goal. The model observes its location on the grid and each action is a move one tile up, down, left, or right.

To simplify the problem, we restrict the map size to 2x2 and keep the environment deterministic. The agent always starts in the top left corner and is rewarded if it reaches the bottom right corner. A hole is placed in one of the two remaining spaces. The agent fails if it takes more than 2 steps or falls in a hole. Each map has exactly one solution.

The agent attempts to cross the lake 1,000 times. To force primacy bias, we show the agent Map 1 for the first 200 crossings, and Map 2 for the last 800. The maps are deliberately chosen to have opposite solutions. After 400 crossings the agent will have experienced each map equally and afterwards the agent should begin to prefer Map 2 with increasing confidence. Our agent is maximally exploitative and will always take the action it thinks is best.

Each trial is considered expensive (our agent doesn’t want to freeze). A good algorithm will maximize the number of successful crossings in the 1,000 attempts. Each attempt is saved to the replay buffer and any reset will fully reinitialize all network weights.

The advantage of this environment is that it is very fast. A trial of 1,000 crossings with a replay ratio of 1 completes in less than 5 seconds on a CPU. The disadvantage of this environment is that it’s incredibly simple, and findings might not generalize to more complex problems.

Results

The first thing we do is inspect how our model scores its first action with and without resets for each cross.

Additional action values overtime for various learning rates.

Both models quickly determine that moving down is correct. The resetting model will periodically score actions equally before quickly recovering. Without resets, the map switch is only recognized after the 800th crossing. With resets, this switch happens around crossing 500. We also see that after the map switch the model without resets tries to adjust by increasing the scores for the incorrect left and up actions (which led to failure in two steps instead of one).

We can also plot the reward per crossing, averaged over 25 seeds. Similar to the first result, the model with resets periodically fails, but also adapts to the map switch faster.

Additional scores overtime for various learning rates.

Next, we conduct a hyperparameter sweep with replay ratios 1, 4, 16 and reset frequencies 0, 50, 100, 500. We then compare the average number of successful crossings. A random policy will earn the reward 1/16 of the time.

Additional averages scores for various learning rates.

In general, the results match our expectations. With a learning rate of 0.01 a higher replay ratio improves results and having resets is always helpful. A high replay ratio with resets is necessary to achieve a score over 0.6 for all learning rates. Reset frequency and replay ratio must be adjusted alongside learning rate which scales how quickly the network can adapt in a non-stationary environment.

As a final experiment, we vary model size. We compare a much smaller two layer DQN architecture to the larger three layer model used in prior experiments. Interestingly, this produces the highest score yet with a reset frequency of 10 steps although the result quickly disappears with a lower learning rate.

Additional averages scores for various learning rates by network size.

Conclusions

In this blogpost, we discuss primacy bias and its application to off-policy deep reinforcement learning. We highlight a subset of results and apply weight resets to a new problem.

We hope that more examples of primacy bias continue to be discovered and studied. Eventually, we would like to identify specific behaviors that are catastrophically memorized and create guiding principles to identify environments that are most at risk of primacy bias. Overtime we hope this might unlock new applications of deep reinforcement learning.

Even as the theory continues to develop, there is little harm in attempting periodic weight resets with a high replay ratio to train off-policy reinforcement learning agents.

Finally, primacy bias might not always be a bad thing. If you decide to take a new shortcut to work by walking down an alley and the first thing you notice is how dark and unsafe it seems then maybe it’s a good idea to turn back. As always, it is an important decision for the modeller to decide if primacy bias should be treated in their problem.

Acknowledgements

This blogpost is derived from our work that began in Dr. Zsolt Kira’s excellent Deep Learning course at Georgia Tech.