Fairness in AI: two philosophies or just one?

The topic of fairness in AI has garnered more attention over the last year, recently with the arrival of the EU's AI Act. This goal of achieving fairness in AI is often done in one of two ways, namely through counterfactual fairness or through group fairness. These research strands originate from two vastly differing ideologies. However, with the use of causal graphs, it is possible to show that they are related and even that satisfying a fairness group measure means satisfying counterfactual fairness.

This blog post is based on the paper of Anthis and Veitch

Why fairness?

The spread of AI exposed some of the dark patterns that are present in society. Some well known examples are the COMPAS case

Fairness in AI is a research strain which aims to remove the biases in the AI models that result in that disparate treatment. The goal of these models is that people are treated more fairly, perhaps even more than a human decision.

What is fairness?

The question of what is fair does not have a single answer. Even when stepping away from the computer science context, a universal definition, that can be used to determine if something is fair or not, cannot be found. The concept of fair is heavily influenced by a person, but also society’s biases. The fluidity of the notion therefore gives rise to multiple philosophies in what a fair AI system would be.

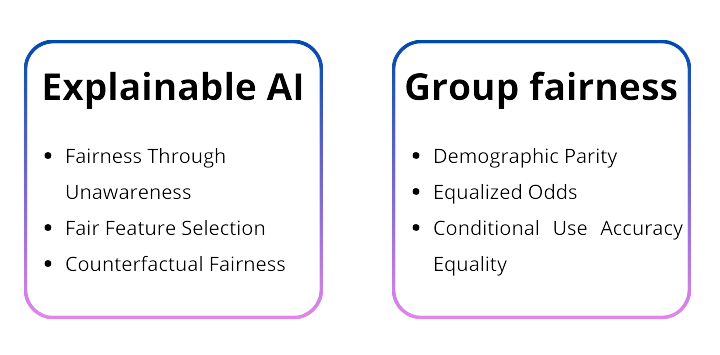

Two main philosophies can be found in research. The first one, often called explainable AI, aims to either create explainable models or to create explanations for the results obtained from a model. This can also be described as aiming for procedural fairness. The second philosophy is called group fairness. Group fairness focusses on outcome fairness. This means that the predictions from the AI system should have similar properties across groups that only differ in a certain personal attribute.

Explainable AI

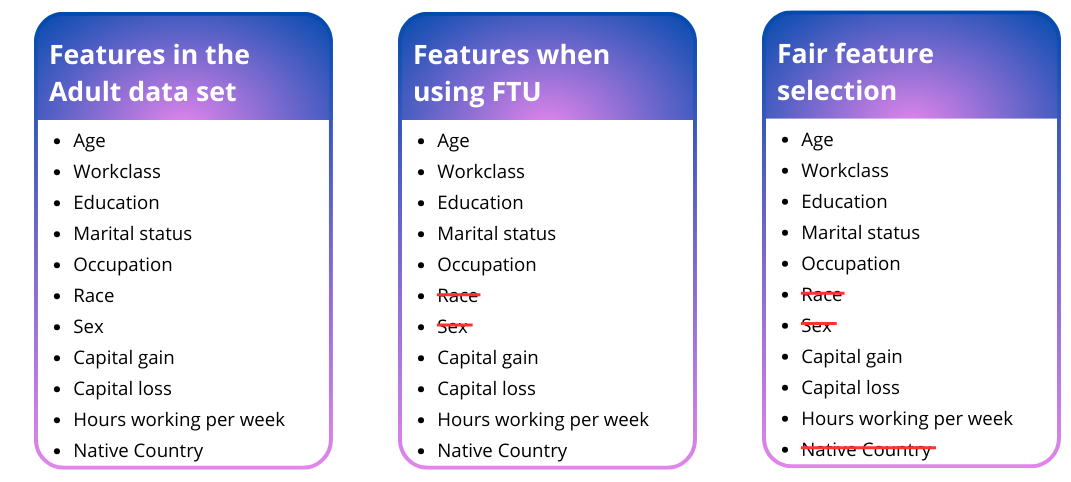

The most famous example of explainable AI is fairness through unawareness. Fairness through unawareness means that no personal attributes are passed into the system, unless these are relevant for the prediction. The system does therefore not have access to the personal attributes, which means it cannot directly discriminate. Fairness through unawareness is often used as the basic model for fairness. However, the systems from both the COMPAS and Amazon example used fairness through unawareness and they still exhibited disparate treatment. The personal attributes that were removed from the data still had an influence on the dataset itself. For instance, a ZIP code can function as a proxy for race or someone’s gender influenced their writing style.

Related to fairness through unawareness is fair feature selection

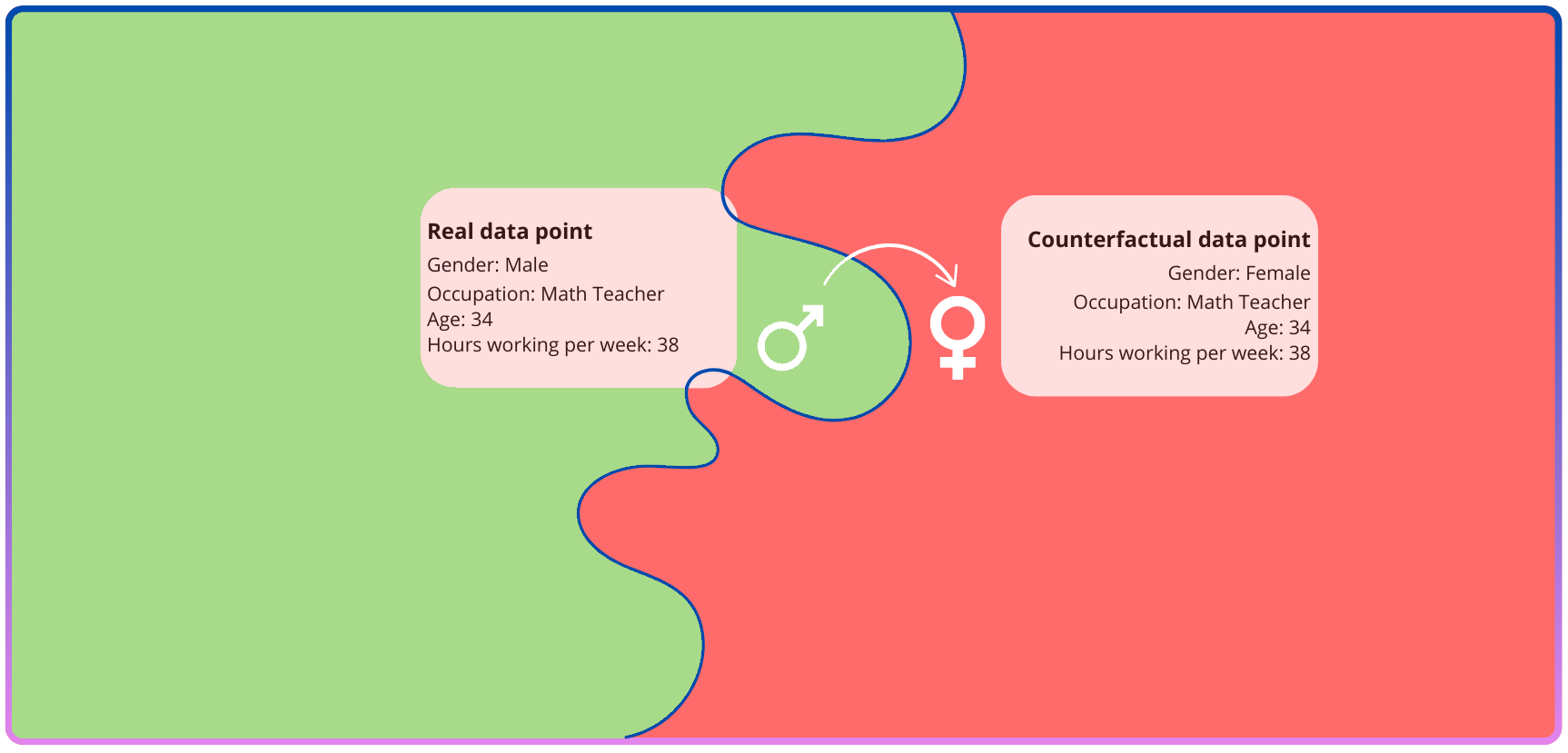

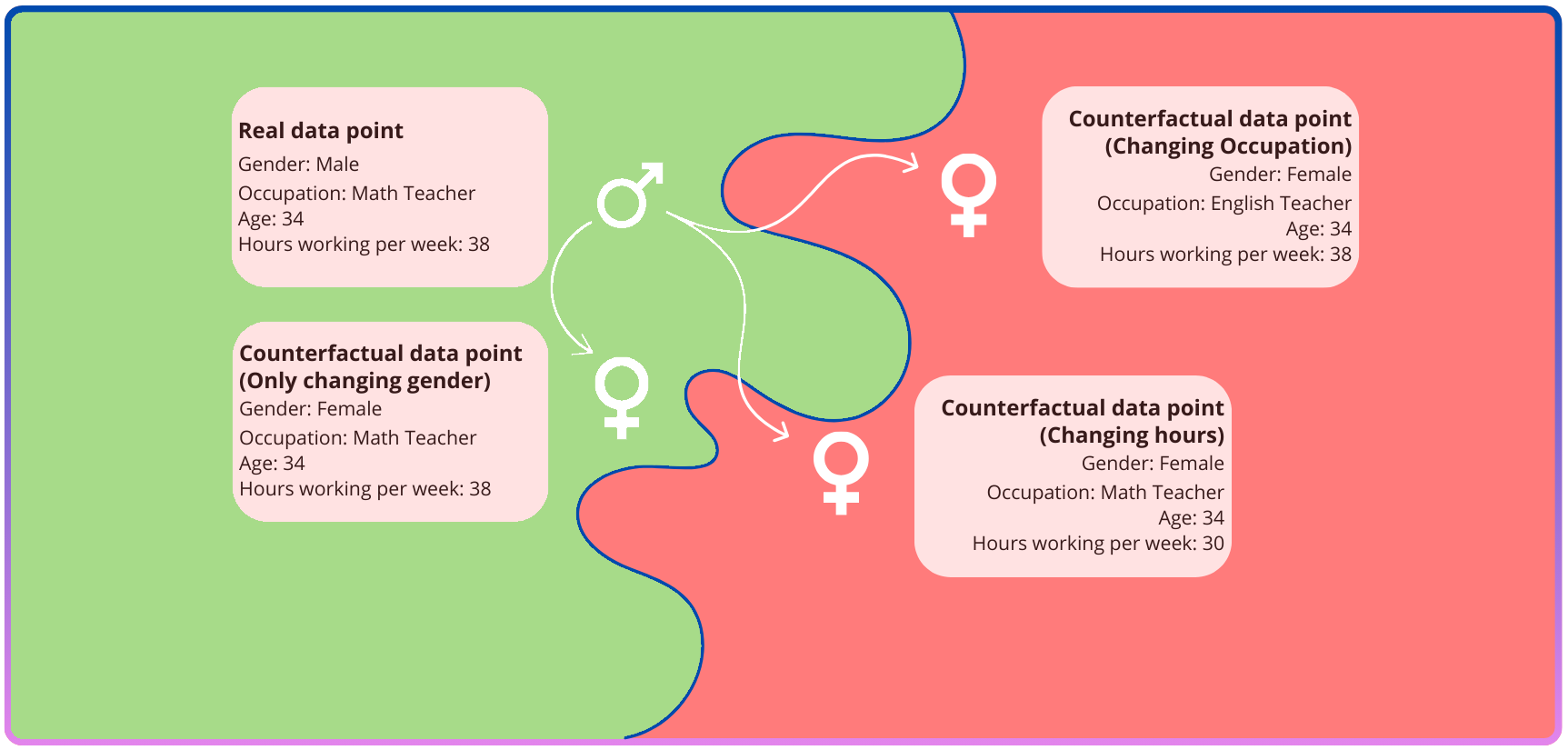

Counterfactual fairness is a currently popular type of explainable AI. Counterfactual fairness stems from systems that check for direct discrimination, meaning that simply changing a personal attribute would change a person’s prediction

Models for counterfactual fairness change both the personal attributes of a person and other features are also adjusted according to a causal model related to the personal attributes

Group Fairness

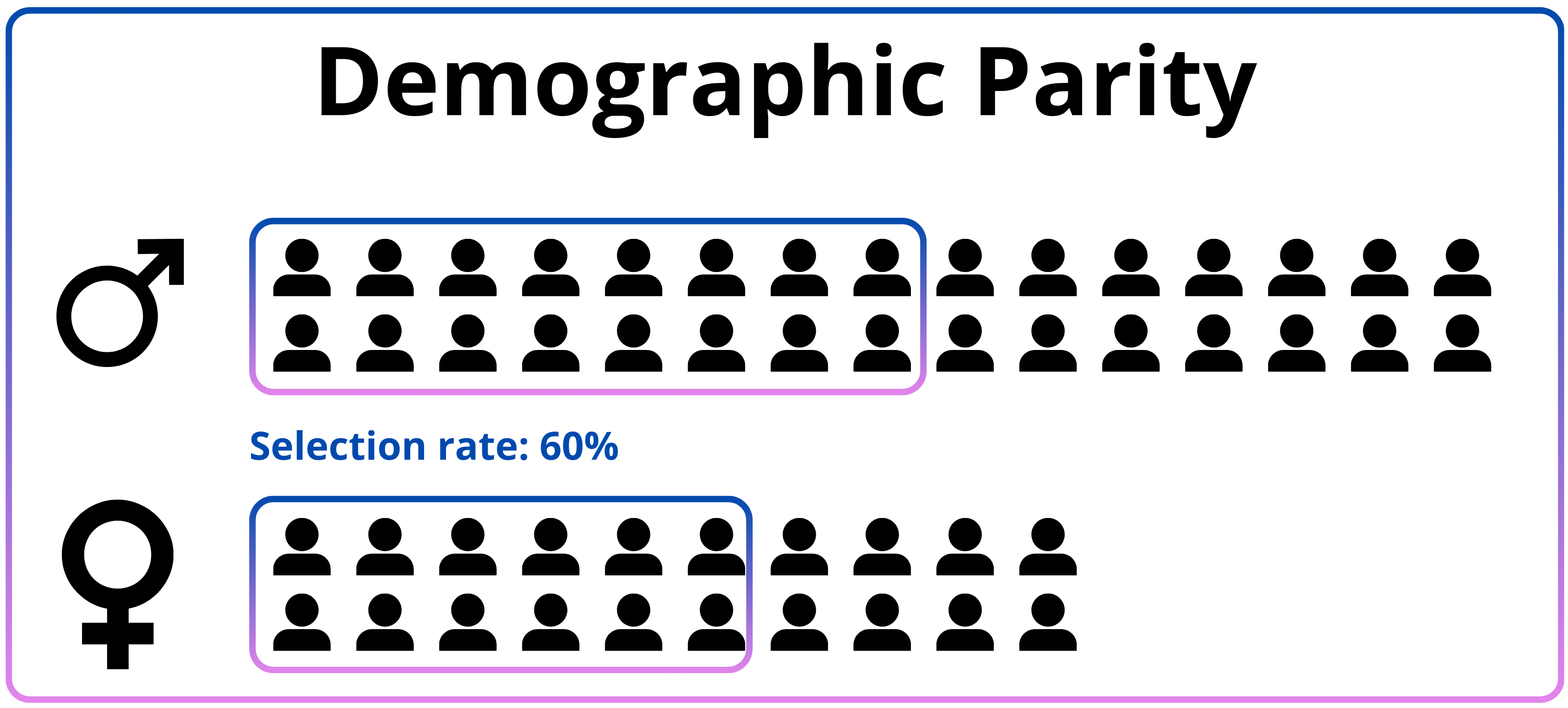

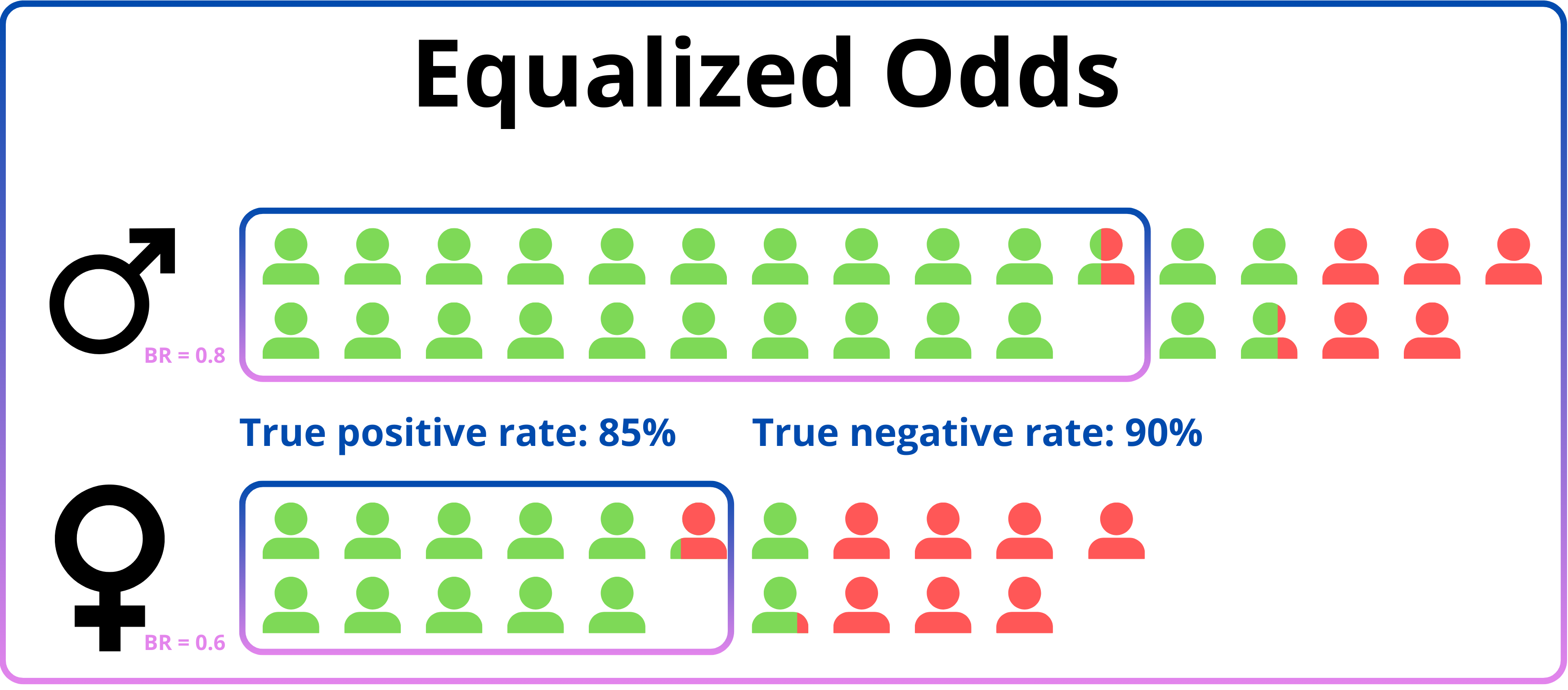

Group fairness is a different philosophy regarding fairness of an AI system. Instead of requiring the process of the system is fair, it requires the outcome of the model to be fair. This verdict of fairness is based on the equality of a chosen statistical measure between groups. People are divided into these groups based on their personal attributes. Three definitions are most commonly used for group fairness namely, demographic parity, equalized odds and conditional use accuracy equality.

Demographic parity

A second fairness measure used in group fairness in equalized odds

The final common fairness measure in group fairness is conditional use accuracy equality

Unifying these philosophies

The previous two sections discussed the different concepts used for explainable AI and group fairness. It is clear that they employ a different basis for their philosophy of fairness. However, when looking at these definitions, the concept of independence returns in both counterfactual fairness and the fairness measures used for group fairness. This property of requiring independence allows to unify these notions that they accomplish the same result

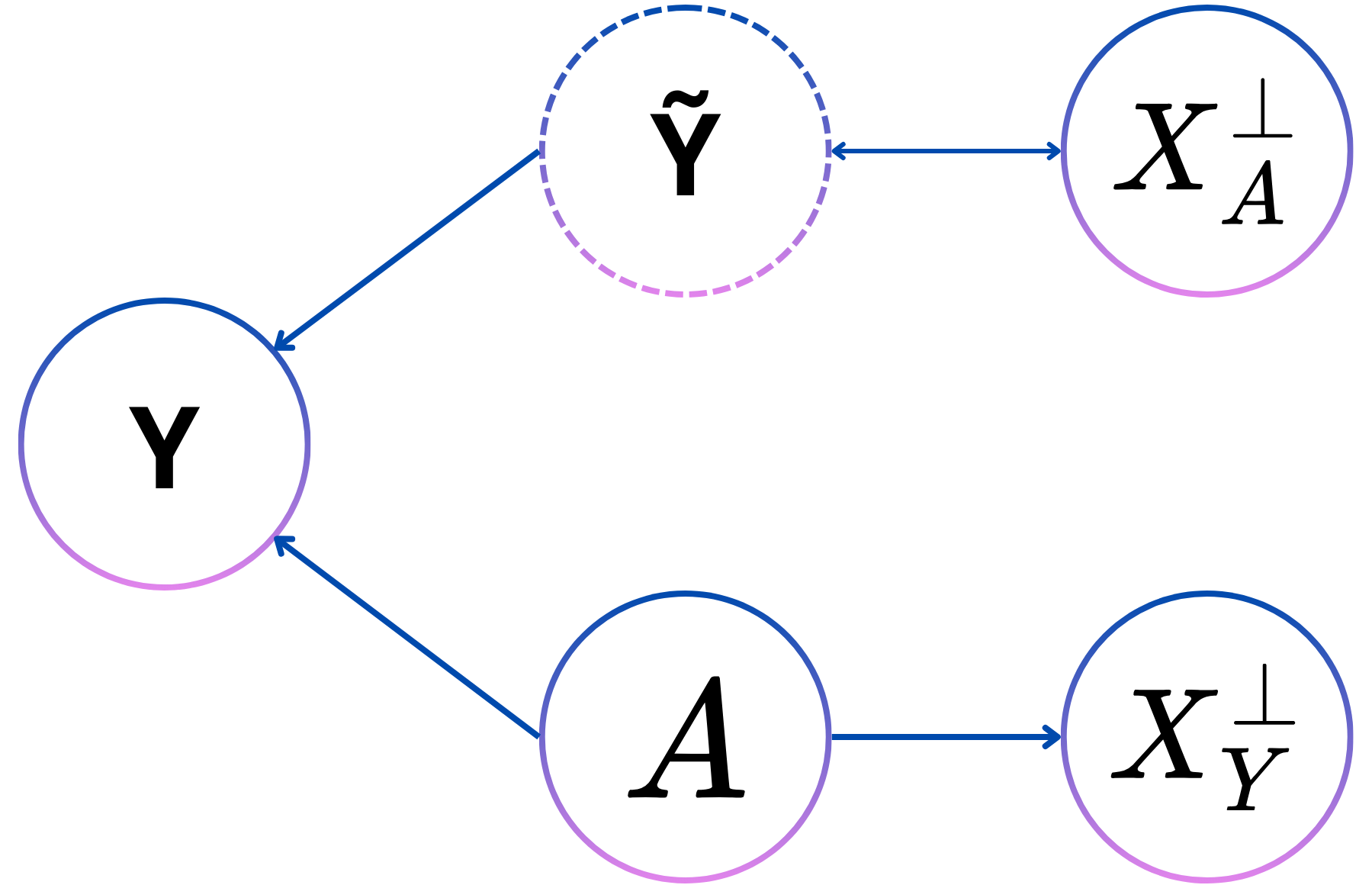

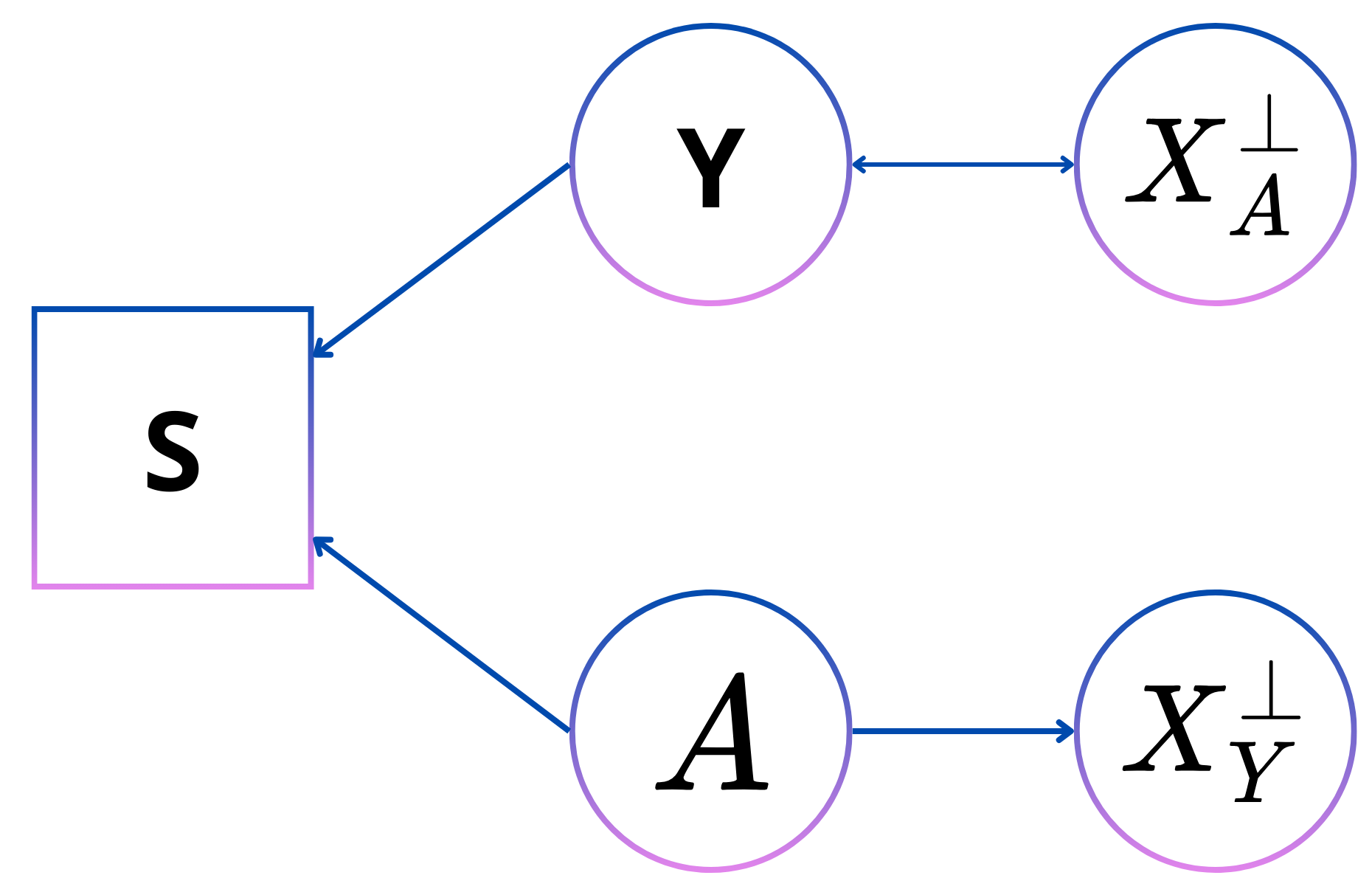

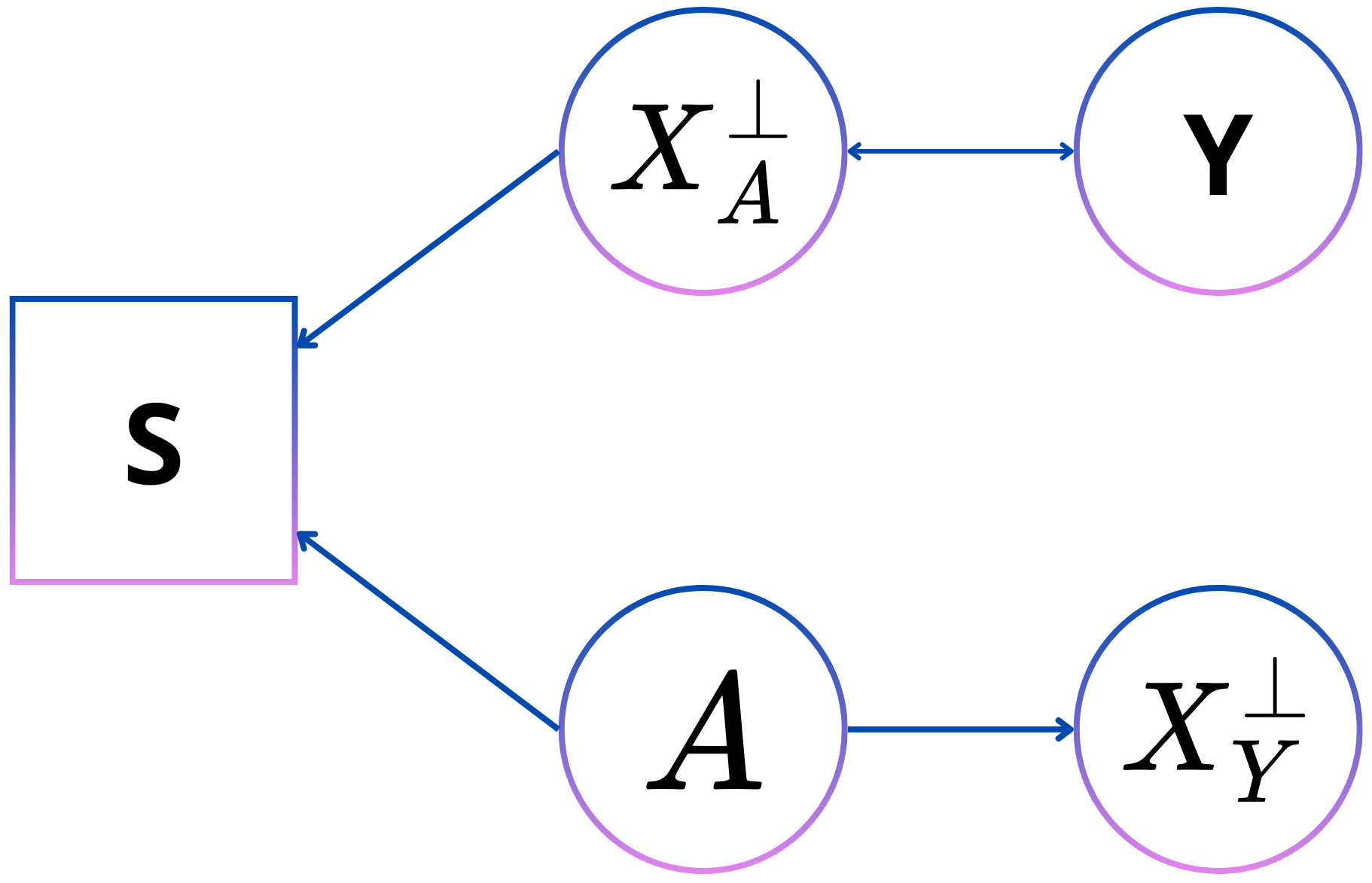

In the following section \(Y\) symbolises the perceived label, \(D\) the prediction, \(A\) the personal attributes, \(S\) the selection of a sample in the dataset, \(X^{\bot}_A\) the data independent of the personal attributes, \(X^{\bot}_Y\) the data independent of the prediction and \(\tilde{Y}\) the real label.

| Name | Probability definition | Independence |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic parity | \(P(D=1\vert A=1) = P(D=1\vert A=0)\) | \(D \bot A\) |

| Equalized odds | \(P(D=1 \vert A=1, Y=y) = P(D=1 \vert A=0, Y=y)\) | \(D \bot A \vert Y\) |

| Conditional use accuracy equality | \(P(Y=1\vert A=1, d=y) = P(D=1 \vert A=0, D=y)\) | \(Y \bot A \vert D\) |

Measurement error - Demographic parity

Measurement error is a first type of dependence that can be resolved in order to be counterfactually fair. Measurement errors means that there is some bias on the perceived ground truth in the dataset. For example in system that determines whether pulling a car over is justified or not (whether a crime was committed or not). More crimes can be uncovered if a full car search happens, however a car search is not always undertaken resulting in a bias of more positive samples for a population where a car search is more likely to happen

A second example of measurement error can be found in healthcare prediction

This system is thus made counterfactually fair if the dependence between the personal attribute and the label is removed. The same independence that is requires to satisfy demographic parity.

Selection on label - Equalized odds

Selection on label is a type of bias that arises by that not only someone’s label affects their adoption in the dataset but also their personal attribute. A subtype of this type of bias is self-selection bias. This means that certain groups of the population are more represented in certain dataset due to that certain groups are more likely to interact with the data collection system. An example of this is in voluntary studies where certain groups are more likely to participate than others leading to a skewed dataset in favor of the participating group. A study around self-selection bias in nutrition trials also found that a person’s ground truth influences their participation in the trial (healthy eaters were more likely to apply for this trial)

The directed acyclic graph in Figure 7 shows how to decouple the label itself with the personal attribute by introducing the variable of the selection bias in S, which is an observed variable. \(A\) and \(X^{\bot}_A\) are only connected through a path that includes \(Y\) which means that given \(Y\), \(A\) and \(X^{\bot}_A\) are independent, which is the condition of equalized odds.

Selection on predictor - conditional use accuracy equality

Selection on predictor is similar to selection on label, but instead of the label influencing the prediction is it the features themselves that influence the prediction together with the personal attributes. An example of this can be seen in the student population of engineering degrees. A relevant feature such as what a person studied in high school influence their choice to do engineering. However, there is a large discrepancy in the number of male versus female student who pursue engineering even though that difference does not exist in that degree when graduating high school. This shows that both relevant features, but also personal attributes influence their presence in a dataset about engineering students.

The acyclic graph in Figure 8 for selection on predictor is similar to that for selection on label. The features and label are simply reversed in this situation. This is also in accordance with the similarity seen between equalized odds and conditional use accuracy equality. Through \(X^{\bot}_A\), are \(A\) and \(Y\) connected, which means that if the prediction is known, which is captured in \(X^{\bot}_A\), then \(A\) and \(Y\) are independent, which is necessary to satisfy conditional use accuracy.

Confirmation with experiments

This relation between counterfactual fairness and group fairness is supported by experiments

A counterfactually fair model is achieved by by taking the average prediction of an instance if it were part of the protected class and if it was not. Three biased datasets are created based on the directed acyclic graphs in Figures 8, 9, and 10. Table 2 shows that satisfying counterfactual fairness for a certain type of dataset will satisfy a corresponding fairness measure, confirming the theoretical results above.

| Demographic parity difference | Equalized odds difference | Conditional use accuracy equality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Error | -0.0005 | 0.0906 | -0.8158 |

| Selection on Label | 0.1321 | -0.0021 | 0.2225 |

| Selection on Predictors | 0.1428 | 0.0789 | 0.0040 |

What can we take away?

Procedural and outcome fairness have tended to coexist in research. They are each their own field with their philosophy with the common goal of creating fairer AI systems. The strengths of techniques like counterfactual fairness lie in their explainability and thus allow for an easier determination of whether they are fair or not. The group fairness techniques know many implementations and have been proven to be powerful. However, they are not very interpretable. In order to determine what is fair a first abstraction must be made into converting the meaning of fairness into a mathematical fairness measure. The determination of whether the system is fair is thus dependent on the interpretation of the fairness measure and the quality of the dataset. If the dataset is not representative then there is no guarantee that the system will have a fair outcome.

This relation between the procedural fairness and outcome fairness opens certain research possibilities, perhaps allowing for the strength of the outcome fairness techniques to be combined with the interpretability of the procedural fairness concepts. A future research possibility is to investigate if the techniques to satisfy fairness measure also satisfy some explainability notions or what adjustments would be needed.